Jenna Maurice, currently a resident artist at RedLine Contemporary Art Center in Denver, discusses how relationships with humans and the natural environment shine through her artworks. She also ponders nonverbal communication and life’s various gray areas.

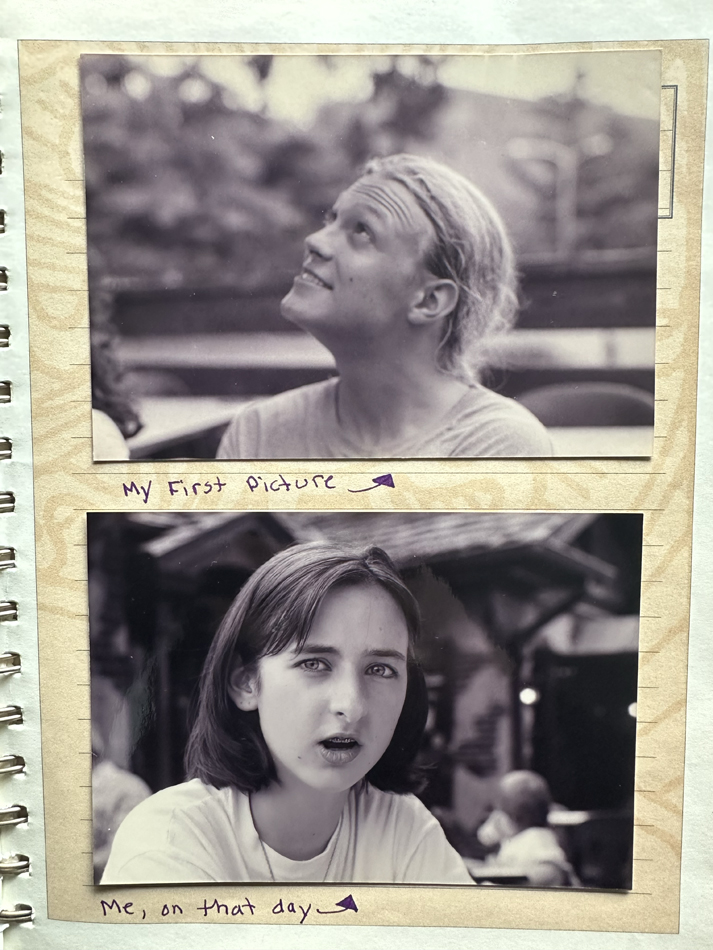

In her photo series So Successfully Disguised to Ourselves (2006), photography, video, and performance artist Jenna Maurice asked her sisters to candidly reflect on themselves and each other, juxtaposing one portrait of how each sister sees herself with another portrait of how the group perceives her.

“My three sisters and I were homeschooled, but we didn’t have long hair and wear Keds,” Maurice jokes. The artist remains close to her family, who have always supported her work and collaborated with her by bravely showcasing their own vulnerability alongside Maurice.

Regarding her older sister’s perception of herself, Maurice shows her struggling to stand after knocking a basket of nuts off a living room coffee table while her sisters observe with disgust. In the accompanying photograph, Maurice positions her apart from her siblings, standing next to her husband’s cluttered work desk as he reads a book. From the sister’s standpoint, her clumsy foibles suffer the constant scrutiny of her siblings. From their standpoint, they feel estranged from her as she embarks on a separate family life.

The pairing of these images demonstrates widely different objective and subjective viewpoints of this sister, weaving an intimate and intricate visual vocabulary of connection and disconnection. Maurice also emphasizes that these portraits reflect understandings formed in a past context, including “a therapy we went through and changed from.” Despite the seeming fixed-in-time presentation of the photographs, these portraits implicitly demonstrate how relationships and perceptions of others perpetually fluctuate.

Completed en route to obtaining her BFA, which she pursued at the precocious age of sixteen, So Successfully Disguised to Ourselves illuminates the ideas permeating Maurice’s work over twenty years later. She credits her upbringing—growing up in Los Angeles before moving to rural Tennessee at the age of ten—with shaping her artistic practice and interests in film, kinships, memory, and non-verbal communication. Establishing herself in Denver in 2009, Maurice received her MFA in interdisciplinary media arts practices at University of Colorado Boulder in 2013. Maurice’s work still involves her family while also expanding into considerations of gray areas, finding rapport with the non-human features of our environment, and the accounts we give of ourselves without spoken language. Additionally, in July 2023, Maurice and her partner, video, sound, and performance artist Adán De La Garza, organized an inaugural Month of Video, bringing their enthusiasm and high standards for the video arts to Denver.

In a collection of filmed performances, Concerning the Landscape: A Study in Relationships (2012-14), Maurice contemplates how features in a natural habitat feel when we walk around them, neglecting to engage with them as we do with fellow humans. These videos depict Maurice integrating herself into the heart of a bush, trudging through a pond, thick with bright green scum, and hugging a field of saguaro cactuses. In a similar piece, Subtle Appearances (2016), Maurice presents herself with the insurmountable task of walking through a mountain. Additionally, attempting to relate to a waterfall in Reacting to the Force of Niagara Falls (2013), Maurice “reacts” by gagging herself. As she purges beside the falls, she enacts an absurd and impactful display of empathetic affinity.

Reflecting on these pieces, Maurice also expresses her interest in the question: “What happens when nothing happens?” During her video performances, she forces the viewer to sit with this inquiry, meditating on still scenes recorded in real-time with no discernible action or movement in the frame. For instance, before entangling herself in a shrub in Concerning the Landscape, the camera freezes on a solitary verdure in a golden-hour prairie for over thirty seconds before Maurice enters the frame.

“It’s interesting to me but also can be boring,” Maurice muses. However, she acknowledges that the “boring” aspect of such works productively challenges her and the viewer to confront their need and expectation for constant entertainment. These still-life videos also challenge our egoistic desire to see ourselves and our experiences reflected back to us, making us question why we might be less amused by scenes void of human activity.

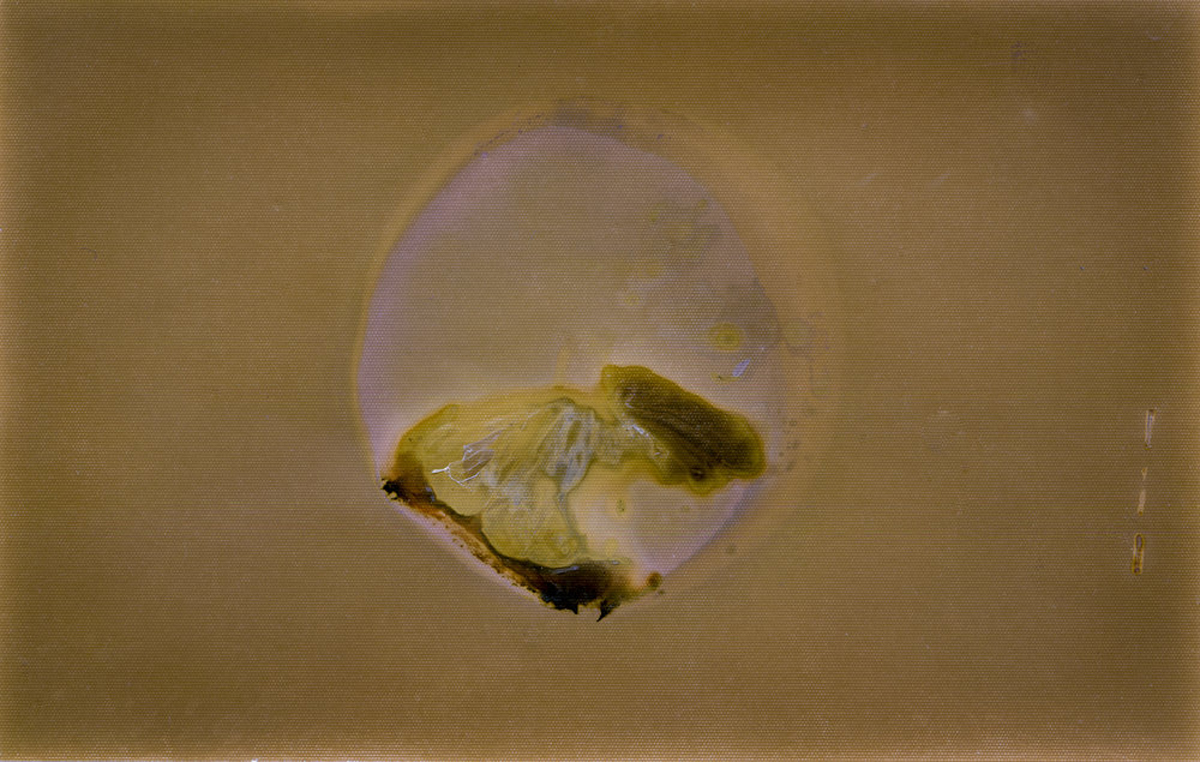

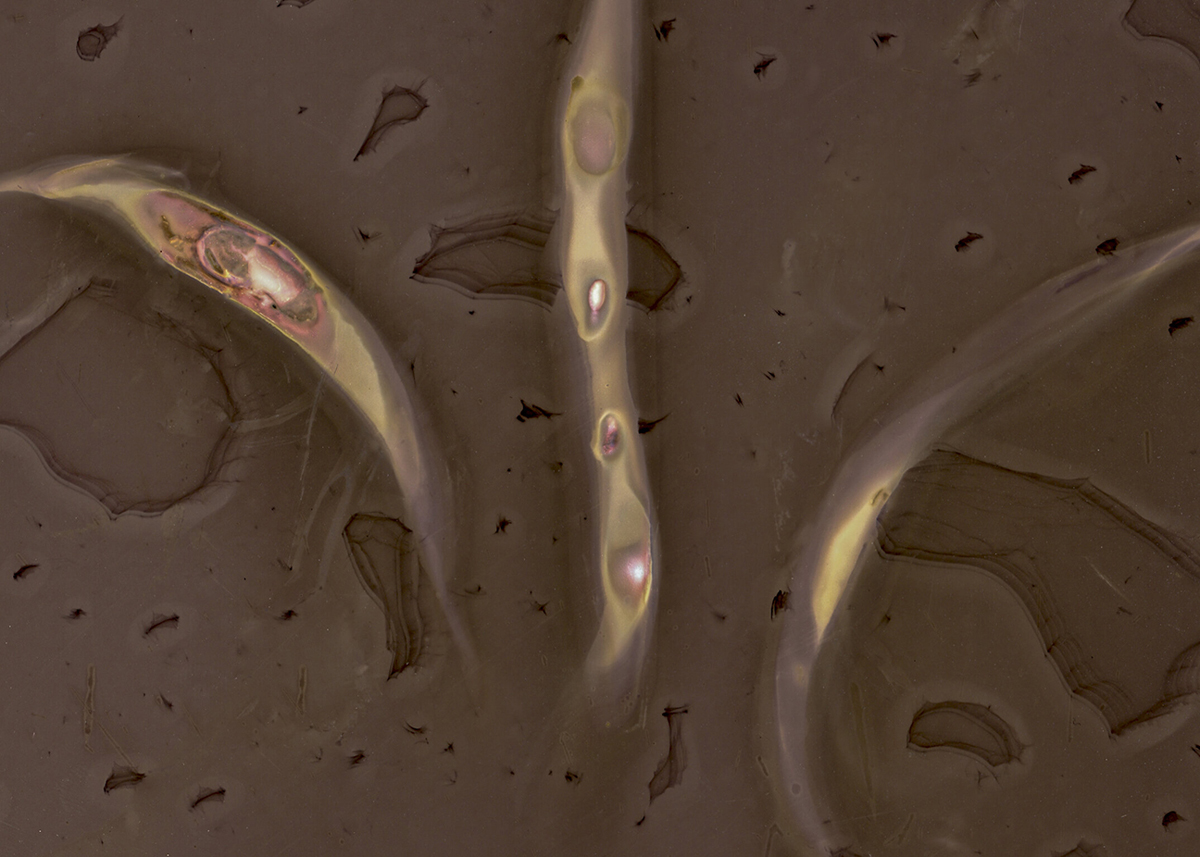

Working with lumen prints in Archive of Things (2023), Maurice probes further into nature’s perspective and secret messages. Placing various objects, such as lemons or grapes, on darkroom paper for several hours of light exposure, Maurice creates haunting prints of the inner worlds of objects. Although she uses black-and-white paper, the objects react with the paper’s chemicals, creating vividly colored designs. “You never thought you could see a galaxy inside a green bean,” Maurice muses.

These works emphasize Maurice’s interest in transcending language to commune with things beyond our experiences of self. However, in other projects, Maurice uses nonverbal communication to amplify a sense of self and self-expression. In Reactions to a Memory of an Experience (2014), she filmed people’s silent reactions to an important mental souvenir. As Maurice beckoned people to play a private story, frame by frame in the theater of their mind, Maurice’s camera centered on their eyes to convey the drama.

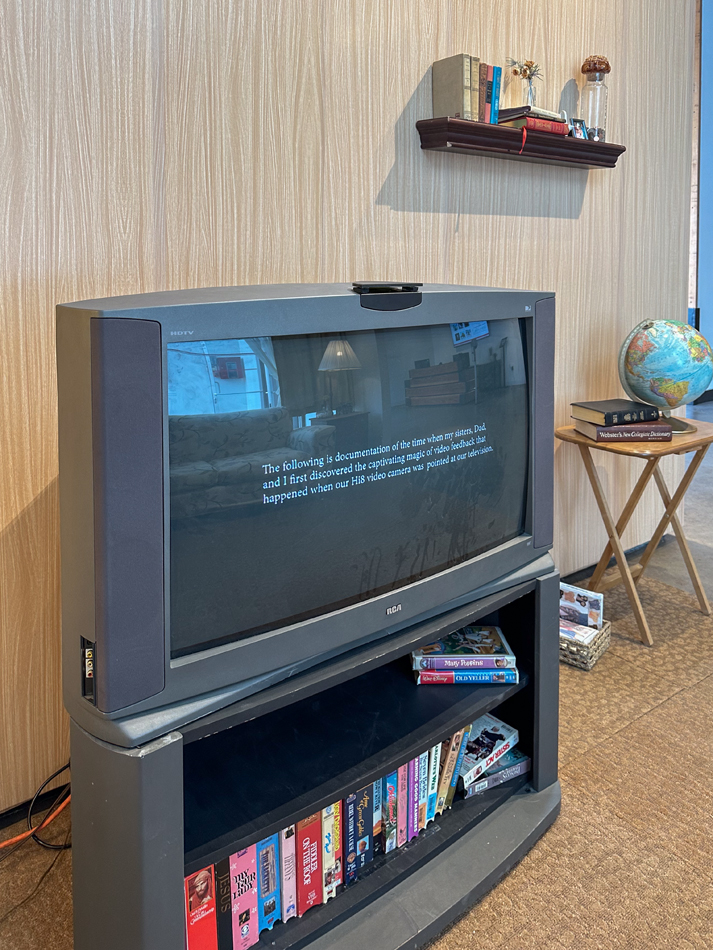

In the recent group show Home Dreams at Denver’s RedLine Contemporary Art Center, where Maurice is a 2022-24 resident artist, she returned her focus to her family and her development as an artist. “It’s just the TV” (2024) brings her memories to life, reconstructing her family’s living room from the 1990s. On a television set, Maurice played a home video that captured her family’s fascination with the video feedback resulting from their Hi8 video camera pointing at their television screen. “We were equally engaged and fascinated,” Maurice tells me. “We all were discovering that the video could be art; I just ended up being the artist who would use it.”

Often building sets for her photographic pieces, Maurice also replicated her family home when shooting her sisters’ portraits for So Successfully Disguised to Ourselves. In another series, Rewriting the Archives (2013), Maurice built installations that allowed her to insert herself into photographs taken by her uncle during a 1969 road trip. Projecting his slides onto a screen and posing in front of them, Maurice initially hoped her uncle would want to revisit and rewrite his past with her. However, he politely declined. For him, the past should not be revised while, for Maurice, the mercurial past presents fertile ground for reinvention.

Compelled to remember and re-frame memory, one of Maurice’s works-in-progress, I Wish I Had One Million Things to Tell You, considers her first boyfriend, who introduced her to his Pentax camera. “[Looking through his Pentax’s viewfinder] changed my life. I saw a rectangle, and [realized that] I could decontextualize anything,” Maurice explains, relating the power to choose the information one captures in a frame.

This piece indirectly retells the story of Maurice at fifteen, when she lived in her family home, sixty miles from her boyfriend. It was the dawn of home computers and internet dial-up modems, and her family shared one email address to which her boyfriend wrote her. Whenever she saw his email in their inbox, she printed it, deleted it before the rest of her family could read it, and retained it with her other missives in a thick three-ring binder. She still possesses this one-sided correspondence. Her replies, unprinted, remain forever irretrievable.

A man reads excerpts from these lyrical emails in I Wish I Had One Million Things to Tell You as Maurice shows an image corresponding to words not yet or already uttered, weaving language and images in a convoluted “game of memory.” This memory game exposes the gray areas of her recollections, inevitably distorted and made into something new as she recounts and scrambles her past experiences.

Indeed, gray areas take center stage in another of Maurice’s upcoming visual essays. Abstract, liminal areas of thought and culture, Maurice further defines gray areas as spaces, situations, or contexts that remain un- or only partially defined. Moreover, as nodes of possibility and confusion, where something new and not yet articulable might emerge, gray areas inch us closer to freedom. As an example, Maurice offers food expiration dates: “What is the exact moment it’s not OK [to eat]?” Artwork also has a shelf life, Maurice points out, adding, “If you make something you think is good, it can be good forever. [Art doesn’t have to have] an expiration date.”

In the current exhibition Beginners at the University of Dayton (on view from February 14-April 24, 2024), Maurice and her partner De La Garza consider this notion of lapsed artwork—and discontinued filmic technology—as, according to their artist statement, they “present video works made from their personal archive of footage shot when they were in their youth… documenting different aspects of their lives and cultures they were embedded in.”

For Maurice, it’s an artistic duty to accept her past self and learn from her mistakes, which is why she proudly and defiantly flaunts her “old,” “amateur” work. Yet, if you click through her online archive, you might miss evidence of this learning curve, focusing instead on a well-composed and ever-evolving story of a portrait of an artist and her family.