Janette Terrazas utilizes her artistic practice to protest against water contamination in the El Paso-Juárez binational region.

This article is part of our Finding Water in the West series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 7.

EL PASO, TX—In August 2021, a nasty, pungent smell began emanating from the Rio Grande that was particularly noticeable to residents living close to the riverbank and to daily commuters crossing the international bridges that connect El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. It was weeks before the public was informed of the source: a sewage pipe broke on the westside of El Paso, causing up to 10 million gallons of untreated wastewater to be dumped into the river daily. It took El Paso Water, the public utility company responsible for the leak, more than six months to fix the issue.

Juárez-based artist and activist Janette Terrazas explains how this is not an isolated incident: “What happened at this moment was that the spillage from El Paso Water concurred with another leak by the Junta Municipal de Agua y Saneamiento (Juárez’s public water utility), which has been active for years and is estimated to dump seventy liters of wastewater per second into the river.”

For years, Terrazas has used her diverse socially engaged art practices to alert the public about pressing issues affecting the region, and through the exploration of the local environment, she also creates beautiful work along the way.

A few months before the El Paso sewage leak, Terrazas was working on a project on the Rio Grande titled Río_Arduino: #sintonizador_textil. The project was a continuation of the artist’s previous work involving the understanding of local fauna and flora as part of a larger ecosystem linked by the flow of the river. With Río_Arduino, Terrazas documented the migration path of the black-necked stilt, and while creating audio-visual recordings of the birds, she noticed the unsanitary state of the river. Using Arduino, the open-source hardware and software technology, in combination with textile trash she found alongside the river, the artist created a radio device powered by solar cells that openly and in real-time transmitted the sound of the migrating birds both through analog and web platforms.

With this exercise, the artist brings to light the historical contamination the river has endured, considering that “this issue has a lot to do with environmental racism because these practices are usually carried on in places with a high percentage of people of color.”

Terrazas further developed the project through a birdwatching stroll, for which she invited the local community to visit the river and where she also presented a temporary on-site installation QArt Code (Pajareada 1), a code also done with textiles that, when scanned, directs the viewer to the online archive of the audio recordings she produced.

Terrazas, whose artistic research focuses on natural dyes and textiles, constantly uses her expertise to educate the public about the ongoing contamination crises of the region.

In April 2022, the artist created a community workshop at Casa de Adobe, a tiny museum that sits on the Juárez bed of the Rio Grande. She instructed the public to work with cochineal–an insect found in cacti–that has been used to produce a bright red dye for centuries. To obtain the pigment, the tiny bugs are mixed with different substances to obtain many variations of the color.

The artist used this chemical reaction to create a visual representation of the state of the water in the river: different shades are obtained depending on the acidity/alkalinity of the substance used to activate the cochineal. Using mixers such as bicarbonate and citric acid, the workshop first created a sample of colors, which served as a sort of scientific control, and then compared them to the colors obtained using river water as an activator. The experiment proved that the water is extremely alkaline, which, the artist explains, is caused by the unchecked disposal of detergents into the sewage of the cities.

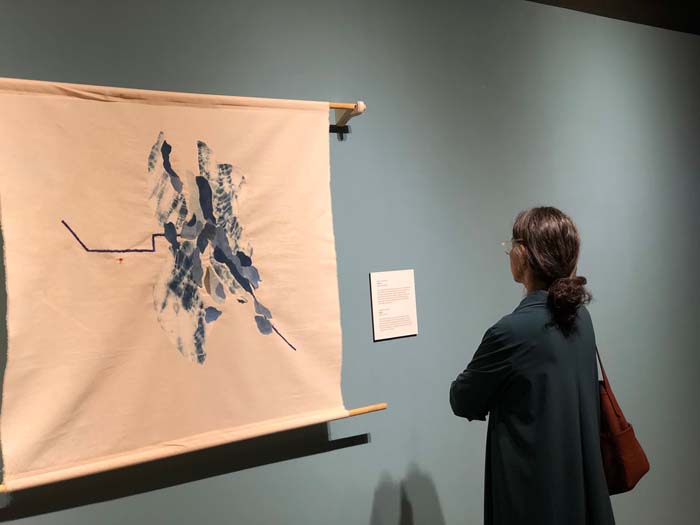

Terrazas furthers the argument of the importance of water as a binational, shared resource with her piece Acuíferos (Aquifers) (2022). This piece, which was shown in the group show Desierto.Arte.Archivo at Branigan Cultural Center in Las Cruces, New Mexico last year, is a map made with indigo-dyed textiles, visually representing how the different water basins are interconnected under the lands of Chihuahua, New Mexico, and Texas. By creating different patterns in the fabrics, the artist evokes the flow of water while informing the viewer of how the region is linked through its underground water sources.

“The idea of these patterns was to create a symbolic representation of the movement of water, creating a conceptual erasure of borders since, for this natural resource, geopolitical divisions do not matter,” she explains.

As we hear about man-made environmental disasters becoming more prominent in the world, Terrazas’s work ensures we do not forget about the horrible state of the regional water resources. Through a practice that offers an alternative, more ethical relationship between humans and nature, the artist is committed to continuing to fight the many actors that constantly endanger our most vital, scarce resource.

In a place that is always suffering different social and natural problems, Terrazas does not lose sight of the urgency of the situation, issuing a constant reminder that we are always a mismanagement away from an irreversible catastrophe.

Editor’s note: Edgar Picazo Merino serves on the board of Ni En More, a nonprofit social organization directed by Janette Terrazas.