Artist Jack Craft operates a cattle ranch in the Texas Panhandle while producing minimalist sculptures and experimental prints.

The first time I met Jack Craft, we were in a meticulously raked “zen garden” art installation and he handed me a shot of tequila in a tiny iron pinch-pot.

The second time I met Craft, he was holding a microphone outside of the gallery I co-founded, calling like a seasoned rodeo announcer.

This was for a collaboration between Craft and architect Sarah Aziz in early 2020 just before the COVID lockdowns: Tumbleweed Rodeo. It was proposed as an installation using Vornado fans to create a “miniature tumbleweed tornado” in the gallery space, with the tumbleweeds picking up and depositing paint onto sheets of paper.

Instead, it was a night of chaos and wild experimentation, with Aziz and some bystanders-turned-participants wielding electric leaf blowers, throwing and thrashing the tumbleweeds, trying to make more than a brushy impression on the paper-lined panels. For the next year, we kept finding little bits of tumbleweed embedded in the crevices of the gallery.

“That’s where I learned how to ‘post-rationalize’ things,” Craft remembers.

We’re driving in his truck over the juniper-studded hills of his ranch outside of Clarendon, Texas, on the northern edge of the Palo Duro canyon system.

The land is not far from where Charles Goodnight established the first ranch in the Texas Panhandle in 1876, within a year of the surrender of the Comanche after the Red River War—marking the end of the nomadic lifeways of Indigenous peoples on the Southern Great Plains. Herds of cattle replaced the bison, and miles of barbed wire fences crisscrossed the land.

Craft’s great-grandfather, a wool grader by trade who immigrated from England in the 1870s, entered the cattle business and found work as a cowboy and ranch manager. After a stint in far West Texas, the family returned to this region and, in 1938, bought the land that Craft operates as a commercial cattle ranch to this day.

We are greeted by a group of expectant cows. After Craft does a head count and deposits some feed for them out of the cattle feeder hitched to the truck, we head up to the house. Built around 1940, with a big screened-in porch and an ancient cast-iron stove, the ranch house is sturdy and worn. In the living room, a wall of shelves holds hundreds of books, with plenty left over, stacked like pillars. On a small shelf perches an assortment of objects in neat rows: stones, fossils, shells, an iron key, a stone head, a cast-silver corn cob.

“I think that’s the first one that I ever made,” Craft says, holding a small but weighty iron “jack,” a six-pointed form evoking an oversized jack from the childhood game, each limb terminating in a rough pyramidal mass. As a singular object, it feels like a talisman that holds some kind of magic within it. In Craft’s current solo exhibition at Kouri + Corrao Gallery in Santa Fe, chains of jacks are welded together to create geometric forms mounted on the walls.

I feel like what I’m doing is preserving what I know of this place. This landscape is more about absence than presence.

The show is titled Horizontal Yellow, lifted from historian Dan Flores’s book about the natural history of what he calls the “Near Southwest.” The eponymous piece in the series stretches eighteen feet across the wall, hung at the height of the horizon, and coated with yellow iron oxide, or ochre. A diagonal line of jacks, colored with red iron oxide, is a nod to Dan Flavin, an early and consistent inspiration. Then there’s a circle, which Craft calls “a departure.” It’s flecked with gold leaf, like a finish that has worn away.

“I feel like what I’m doing is… preserving what I know of this place,” Craft says of this current body of work. “This landscape… is more about absence than presence,” he says. There is an austere beauty to this part of the Plains, with its endless horizon and wide-open sky. “At large, people sort of revile this part of the world for being flyover country,” he continues. “I love this part of the world. It’s home.”

After high school, Craft majored in economics at Texas Christian University, and studied in London for a semester at the Institute of European Studies. He worked for his father on the ranch before quitting, disillusioned by what seemed like dead-end work. He traveled to New Zealand and Australia, doing back-breaking work for cash under the table, building stone walls from fields full of volcanic rock. He then returned to the ranch.

These were some hard times for Craft, marked by loss. “When I got to art,” he relates of his college years at TCU, “I was able to address some abstract, big things, in my own way.” He started out making jewelry, then moved on to iron pours, enchanted by the process and the heat.

Craft recounts several formative exposures to Minimalism. Lawrence Wechsler’s biography of Robert Irwin is a deep influence. Seeing Flavin and Donald Judd at the Menil Collection: “It blew me away… you could see how [Flavin] was sculpting space with the light.” At Dia Beacon, Craft found Richard Serra’s monumental steel “oppressive,” but Fred Sandback’s planes of space outlined with yarn inspirational.

Integrity is of central importance to Craft, he says: “things being as they appear.” Drawn to iron as a medium (bronze has too much art historical baggage), Craft’s sculptures hold actual weight. “I want it to be solid. If it looks solid, I want it to be what it looks like,” he says. “And I think that that is really hard for people to grasp today, in a world where everything’s virtual or ephemeral or plastic.” In Craft’s world, on the ranch, with his horses and his cattle, craftsmanship and material integrity are “of life and death importance.”

I want it to be solid. If it looks solid, I want it to be what it looks like.

In Craft’s in-town studio—a garage space off of Clarendon’s brick-paved town square—a nine-foot-long iron bar, ridged with those same pyramidal forms, stretches between us on the ground. The new addition to the studio is a massive printing press, which Craft went to great lengths to procure and move into the space.

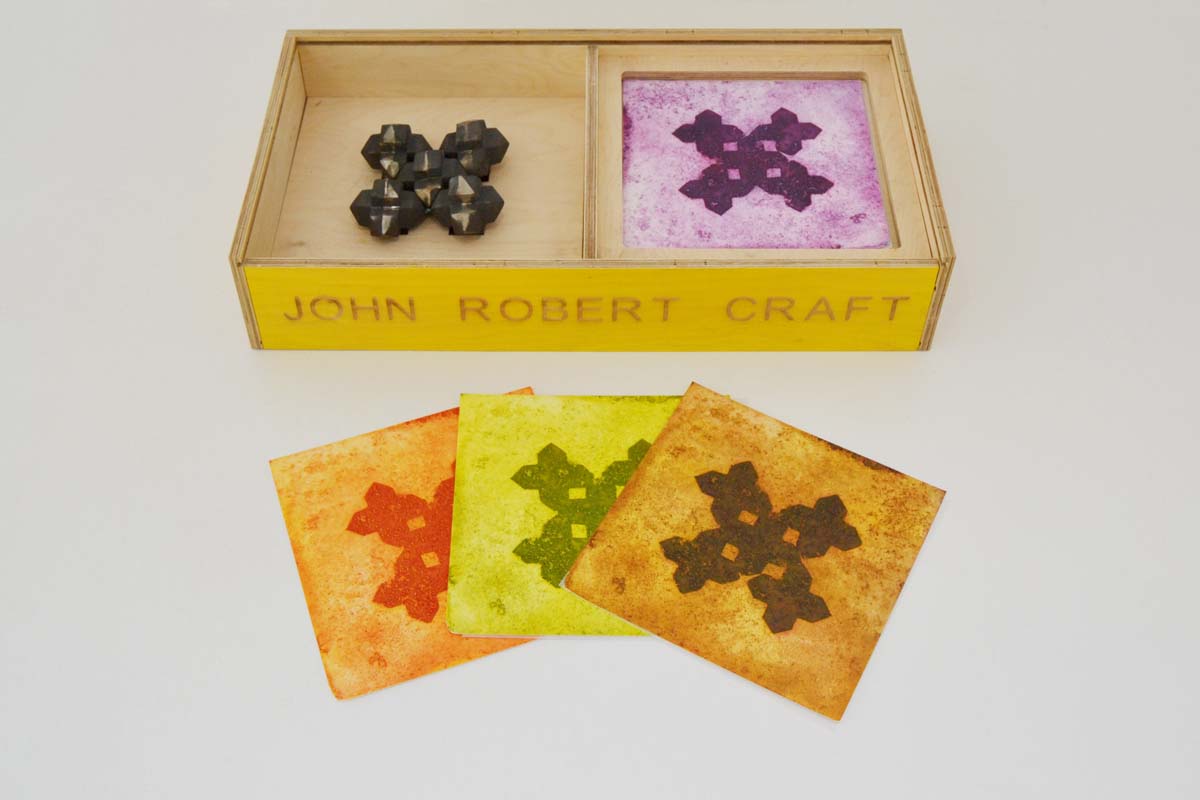

Craft’s sculptures double as tools he uses to make prints. “These works are honest in the sense that there are no tricks,” he says. The dimensions of the sculpture dictate the scale of the print; its mass and weight determine the type of mark on the matrix. His approach to printmaking is highly experimental. One of the print series on view at the gallery explores the different effects of iron when activated by heat and oxidation, resulting in craters of color that look like the surface of distant planets. “I’m not trying to create a particular image,” he says. “I’m just kind of letting the tool do its job. To quote Sarah Aziz: post-rationalize,” he says, a bit facetiously.

In Craft’s artistic practice, his occupation as a cattle rancher, his roots in the land and connection to place, combine with curiosity, experimentation, grit, and a measure of grace. His work in the gallery setting is meticulous and spare, yet he also holds space for the possibility of anomalies and adventures, like tumbleweed rodeos. I ask him about that first night, that odd combination of tequila and tea ceremony, and his fascination with Eastern philosophies. “I’ve always felt like, with really true cowboy work, that there’s this zen-like quality,” he says, describing the equanimous intuition in handling animals that’s far superior than any brute force. There’s something there too, with how Craft handles his materials, from the heat of the iron pour to pulling a print. Salt-of-the-earth authenticity, an honest work.