form & concept, Santa Fe

May 25 – July 21, 2018

For most people who aren’t astronomers or astrophysicists, outer space is a nebulous concept (no pun intended). How we relate to ideas like space-time, the Big Bang, and black holes often has more to do with our immediate material surroundings than with equations and formulas. My own experience of watching Halley’s Comet involves a strong memory of the vanilla-chocolate swirl ice cream cone my father bought for me when we waited to catch a glimpse of it—a moment that I don’t remember at all. On one hand, my childhood mind grasping at quotidian details reflects an inability to comprehend the enormity of outer space. Then again, everyday human life is inextricably connected to our conceptions of the universe in ways that aren’t always grandiose. I understand the rarity of Halley’s Comet because I remember that ice cream cone.

The artists in Inner Orbit see our tendency to think about the small-scale implications of outer space as an opportunity for further exploration—not into the workings of the cosmos necessarily, but into the details that make up our world here on Earth. Andrew Yang’s two-channel video, Interviews with the Milky Way, features the artist’s friend Jeff, an astrophysicist, and his mother Ellen, a child psychologist. The subjects relate personal stories about the Milky Way, which Yang pairs with archival video and film footage of both celestial and terrestrial scenes that evoke outer space. Prompted by her son, Ellen Yang offers anecdotes about breastfeeding him, and their brief conversation leads finally to death and the afterlife as she muses, “I used to think of the afterlife as us being put back in the universe. That’s enough, right?” Her rhetorical question echoes the ideas in Matthew Mullins’s painting The Sun in Our Bones, which includes black paint made from burnt cow bones, forging a literal connection between the calcium and phosphorus that exist both in our own bones and in stars.

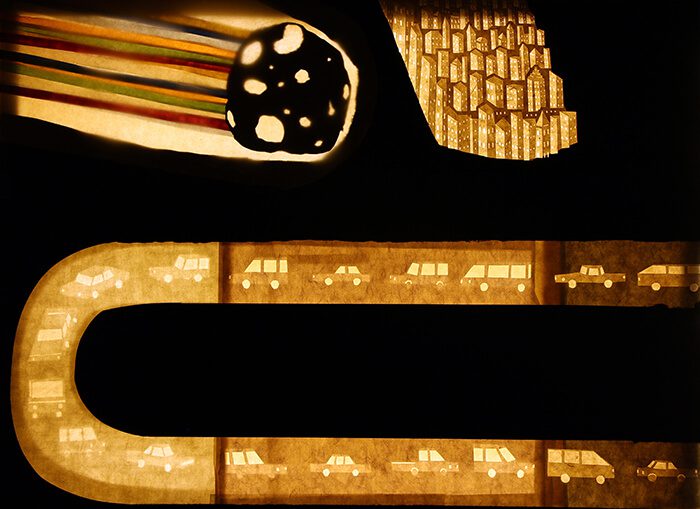

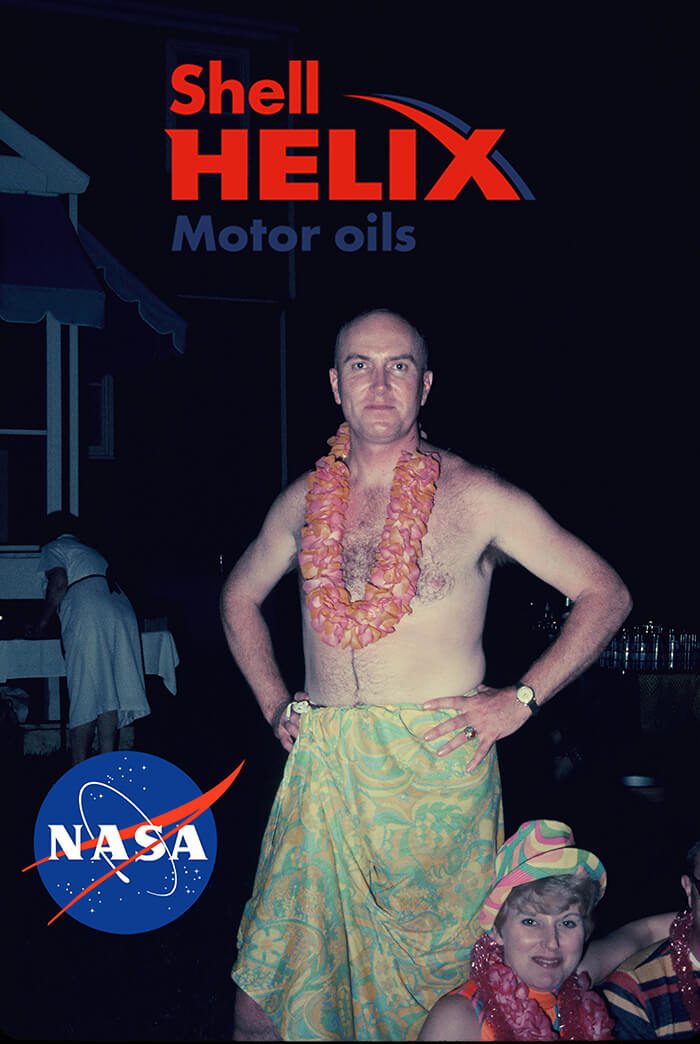

Dreams of outer space can sometimes turn into nightmares. Some of the artists in Inner Orbit employ tropes and histories of the exploitation of humans under the guise of cosmic phenomena. Drew Lenihan’s The Luau includes a series of photographs of his grandfather’s family, the Eagletons, as they celebrate his grandmother’s birthday in their Texas backyard, bedecked in Hawaiian garb. The photos feature intimate family snapshots superimposed with the logos of Mr. Eagleton’s employer, Shell Oil Company, and its affiliates, NASA and the U.S. Navy, and thus with the mechanisms of capitalism and consumerism that made the space race possible. Katie Dorame’s Neophyte Baptism, based on paintings she viewed at Spanish baroque missions, replaces the heads of Spanish colonizers with iconic alien heads straight out of Roswell—a not-so-subtle suggestion that the Spanish were not saving indigenous peoples so much as inflicting inhumane violence on their way of life. Nina Elder portrays the transport of the meteorite Ahnighito to the Museum of Natural History in New York. The meteor itself appears as a white mass of negative space in the center of an otherwise meticulously rendered charcoal drawing, at once a refusal to represent an object of looting and a deft representation of loss for the Illoqqortoormuit Inuit community, which considers the meteorite sacred.

Marcus Zuñiga’s video duration relies on our ability to recognize a yellow, spherical spinning object as a sun, even if the images used to create that image are actually shots of desert landscape. Zuñiga accelerates his spinning sphere to a maddening speed, a reference to the Aztec conception of time as circular and cyclical, and separated into eras known as “suns.” This brings to mind a statement by art critic Gene Swenson: “Most of us, after all, still say that the sun rises; it does make a difference—and one not really socially permissible—if we say that we have turned to the sun once again.” In other words, how we orient ourselves in relation to outer space matters. It’s up to science to tell us facts, to reveal heretofore-inconceivable truths, but it may be up to art to change how we incorporate those truths into our social structures and our daily lives.