Do muralists have a legal right to keep their work from being altered or whitewashed? Experts and artists in the Southwest discuss artist contracts and the Visual Artists Rights Act.

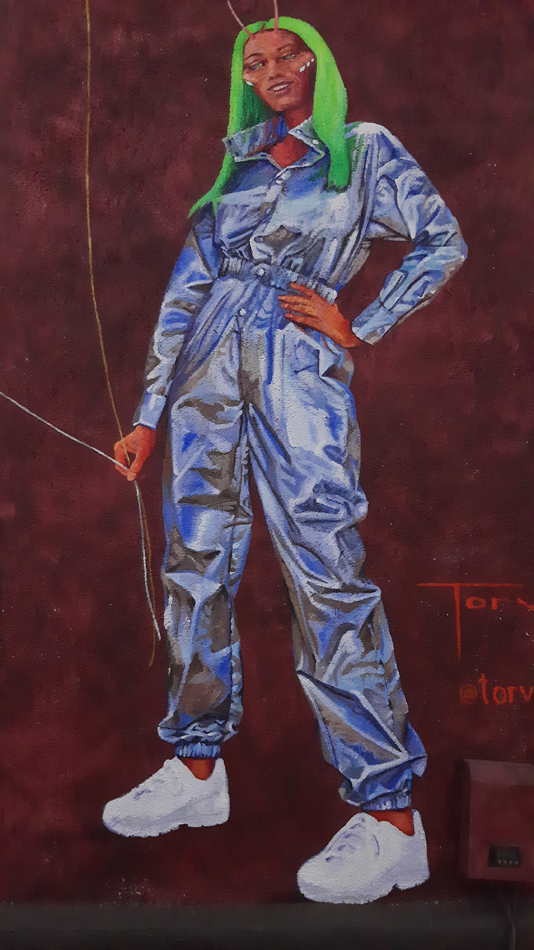

PHOENIX—Artist Lucretia Torva recalls painting the humanoid image of an alien from outer space holding a trio of balloons referencing local landmarks in 2022, using the front of a bungalow that housed a bar and music venue as her canvas. The art piece is located in a section of Phoenix’s ever-changing Roosevelt Row arts district.

Now, she’s lamenting the fact that her mural was painted over in late 2023 after a new owner acquired the building with plans to open a new business at the site—and she’s calling to mind a section of United States copyright law called the Visual Artists Rights Act, hoping it might provide some kind of legal recourse moving forward.

“Artists, property owners, and business owners need to know this law exists and that artists have rights,” Torva says.

Also known as VARA, the law, adopted in 1990, applies to several types of visual art. It protects the integrity and attribution of applicable works, according to Dave Ratner, a band manager turned attorney who heads the Creative Law Network, a law firm based in Colorado and New York that specializes in the creative arts.

“The law certainly applies to murals,” says Ratner, whose practice is located in Denver’s renowned RiNo art district. But that doesn’t mean every mural has VARA protections, as Ratner explained during a recent conversation.

One of the problems with the act, he says, is that a “work of recognized stature” has more protections—yet the term isn’t precisely defined in the law. “That’s what we end up going to court over,” Ratner says.

One of the best-known VARA cases involved a group of graffiti artists who won a $6.7 million judgement after suing a developer who whitewashed their work at the New York graffiti mecca 5Pointz in 2013.

Such victories are relatively rare, according to Sherri Brueggemann, who leads the public art urban enhancement division of the arts and culture department for the City of Albuquerque.

“It’s only been tested maybe two dozen times, and by and large there are only a few cases where muralists have actually been successful in meeting the criteria,” says Brueggemann, who notes that she’s not aware of any mural artists in the Southwest who’ve won a VARA lawsuit.

So what does that mean for artists who want to have some recourse when their mural art gets altered or destroyed?

“Mural artists should have a written agreement with the property owner regarding who is responsible for what and for how long,” says Brueggemann. It’s helpful, she says, when sellers notify new buyers of any agreements they’ve made with artists who’ve created work for the site. As Torva can attest, that doesn’t always happen.

Online resources, including fact sheets, workshops, and the law’s text can help mural artists and others learn more about VARA. In addition, there are several non-profits in the Southwest and across the country whose work focuses on legal issues in the creative arts, such as California Lawyers for the Arts and Texas Accountants and Lawyers for the Arts, or TALA.

The artist Niz, a prolific muralist based in Texas and Mexico, recalls turning to TALA for pro-bono legal advice earlier in her career, then hiring one of its lawyers to help with her ongoing art practice. “That was a game changer for me because like a lot of beginning artists, you tend to sign contracts without knowing much about the legal language or things like copyright law.”

Ideally, every artist would have an attorney to assist them, according to Ratner. Recognizing that’s not always an option, he suggests that artists writing their own contracts use plain language rather than legalese and that they make sure they understand everything in any contracts they sign. “Having a clear and complete contract is really important,” he says.

New Mexico-based artist Jodie Herrera says she’s never used an attorney, despite facing a significant challenge to a 2021 mural commissioned by the owner of a plaza in Old Town Albuquerque. Instead, she relied on community support to prevent a city commission from painting over her artwork after they alleged it was inconsistent with the area’s design guidelines.

“People were upset that they would want to deface a mural by a woman of color from New Mexico,” she says, recalling that over 1,000 people signed an online petition to keep the work that features blooming cactus, a monarch butterfly, and multicolor geometrics. “In that situation, it really was the people who stood up—and it felt good that people wanted to be aware of these things.”

Portland, Oregon-based attorney Kohel Haver recognizes that community buy-in can play an imperative role in demonstrating a mural’s significance. In some cases, he says, murals have importance to a particular cultural community, citing the example of works that address historical or contemporary experience of Black or Chicano residents. Haver also notes that groups such as the Chicano/a/x Murals of Colorado Project can help spearhead local or regional preservation efforts, as can organized efforts to present mural tours, festivals, or maps.

Torva says she wishes the Roosevelt Row Community Development Corporation, whose stated mission includes advancing “arts-focused initiatives for artists, entrepreneurs, and residents,” would do more to educate artists and business owners about VARA protections for mural art.

Artists Niz (left) and Barbara Siebenlist Palomor with a 2023 mural collaboration in Cancun. Photo courtesy of Niz.

During the last decade, several well-known murals have been destroyed or covered in Roosevelt Row, including JB Snyder’s Dressing Room 3.0, his third iteration of a colorful geometric abstraction first painted in 2010 on the side of a building where it’s been a popular spot for selfies and professional photo shoots. The alt-weekly Phoenix New Times named it the city’s best mural in 2017, the same year Snyder’s work appeared on the cover of the Downtown Phoenix directory and map.

Today, it’s cloaked behind a wood façade installed by the latest eatery to occupy the space—and Snyder says the attorney he contacted about pro-bono representation hasn’t been helpful in securing protections for the piece.

For artists seeking practical strategies for establishing or documenting the significance of a particular mural, Haver offers several suggestions, including noting who commissioned the mural, making sure the mural is signed, and applying a protective coating to reflect the intention that it be a long-term presence. In addition, artists and others can substantiate mural-focused media coverage, unveiling events, and social media posts.

Haver notes that formally asserting an artist’s rights under VARA can sometimes curtail the need to take legal action, recalling a letter he sent to parties who were planning to paint over a 9/11 mural created by children at their school and the subsequent compromise between parents who supported the mural and those who objected to it.

“It’s best to research your VARA rights when you hear someone is thinking of doing something to your work rather than afterwards,” says Haver. “That can prevent things from getting ugly.”