Guggenheim Museum

October 12, 2018-April 23, 2019

A Swedish girl joins her first séance at seventeen. Her mind swirls with a heady mix of books on Theosophy, Rosicrucianism, Buddhism, and spiritualism. This doesn’t set her apart; the occult is mainstream in 1879. The following year, her ten-year-old sister Hermina dies while Hilma af Klint attends the Technical School. Her lifelong investment in spiritualism solidifies. By the time she is thirty-five, she has completed her training at the Royal Academy and been given a studio in the center of Stockholm, has joined the Theosophical Society and the Edelweiss Society, a spiritualist organization, and, most importantly, has started a séance circle with four female friends called The Five (De Fem).

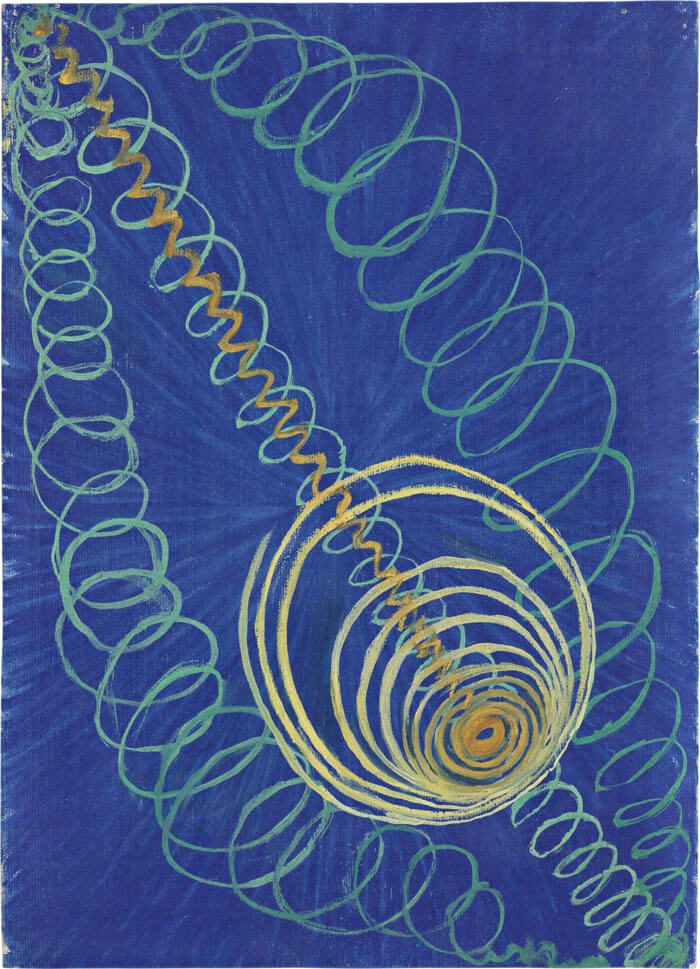

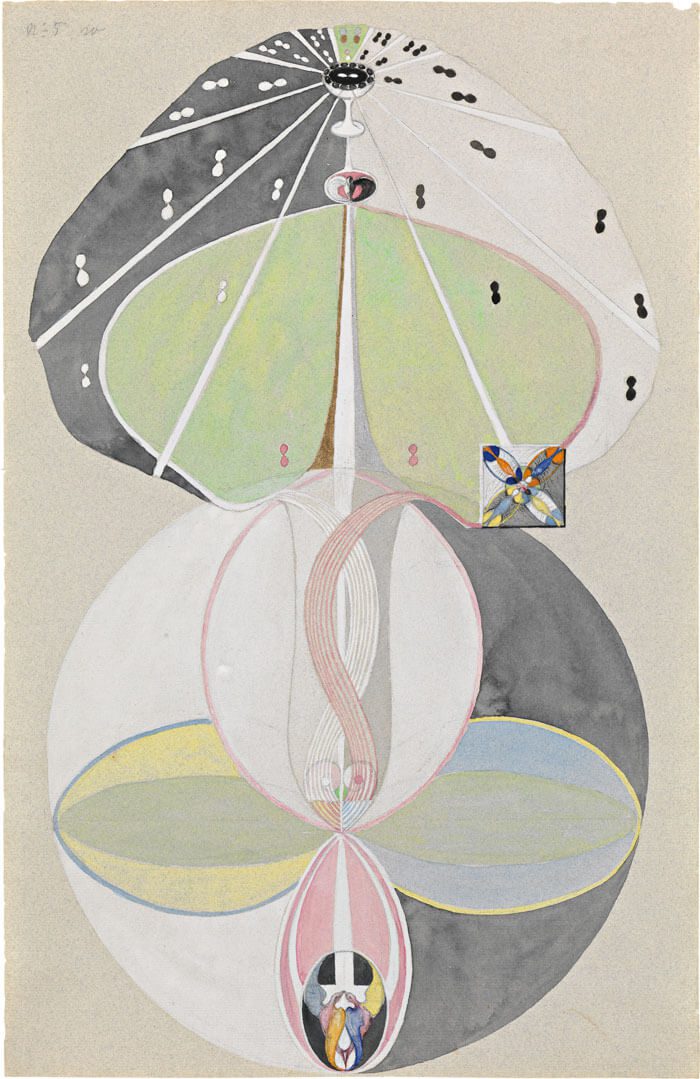

Covens seem to be everywhere these days, from the big screen (Suspiria, Hereditary) to the small (The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, American Horror Story). For af Klint, whose artwork, biography, and influences are explored in the exhibition catalogue for Hilma af Klint: Paintings from the Future, sitting in a circle of five women allowed her to connect with spiritual guides that eventually commissioned from her The Paintings for the Temple, 193 astonishing works (many of which are on display at the Guggenheim through April 2019). Perhaps witchiness was, as it has been historically, a way for af Klint to seize power and authority in creating works of art entirely her own within a society that insisted women artists were only capable of making copies. Perhaps she truly communicated with spirits and had visions that guided her practice. Quite likely, as women who run in circles of women often are, she was a lesbian. Readers can glean this possibility only from the timeline of her life, in which she never marries, but has a series of enduring friendships with women, including her mother’s nurse, Thomasine Anderson. In any case, she knew that her work would not be understood by her contemporaries, and wrote in one of her 125 notebooks, which she left to her nephew, that she intended her over 1000 works not to be exhibited for twenty years after her death. In the notebooks, she diligently reproduced and annotated the works so that future viewers might understand her project.

Perhaps witchiness was, as it has been historically, a way for af Klint to seize power and authority in creating works of art entirely her own within a society that insisted women artists were only capable of making copies.

The exhibition and the catalogue both make it clear that art historians, curators, and artists are still struggling to understand af Klint’s work, her life, and the significance of both. In a transcribed round-table interview, the participants approach their subject like detectives looking for clues. Was she an artist, if indeed her works were spiritual commissions? Is she, as many suggest, among the first abstract painters? Is her work even abstract? Her paintings often engage with spiritual or scientific themes (chaos, evolution, eros, swans, stars). When the contributors delve into the scientific texts, spiritual concepts, shifting technologies of seeing the world and the human body, and diagrammatic style pervasive in print at the time (in both medical texts and books on occult practices), the complex themes with which af Klint engaged so deeply become more legible. The essays in the catalogue that explore these ideas are far richer and more evocative beside the works themselves than, say, the ones that try to pin her to Kandinsky. That said, if it were Kandinsky who had imagined a spiral temple in which his works would reside, as af Klint did, it probably would have been built by now.