Writer and poet Laura Neal visits Theresa Chong’s Dallas exhibition dedicated to the organization of grief, and finds the power in the familiar and heavy emotion.

At some point in our miraculous and fragile lives, we will lose something or someone. We master the art of losing daily. Even with all of life’s celebrations, breakthroughs, and fresh starts, someone always dies in January. Grief, then, is recursive and our relationship with it is inevitable. So how do we come to terms with grief? How do we manage life knowing there are no sharp distinctions between exits and exists?

When I learned of artist Theresa Chong’s exhibition Duino Elegies at Holly Johnson Gallery in Dallas, I recalled the first time I read Rainer Maria Rilke’s poetry book of the same title. Rilke’s collection of ten elegies—written more than 100 years ago while he was a guest of Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis at Duino Castle near Trieste, Italy on the Adriatic Sea—is full of outstanding devastation. With the prevailing deaths from COVID-19, blinding insurrections, and ravaging injustice, the Duino Elegies seem sadly and remarkably fitting for our time.

Initially, I conceived Chong’s show (which was on display from November 20, 2021 through February 13, 2022) as a sort of translation project seeking to transcribe Rilke’s grief. However, after I arrived at the gallery, I quickly learned that Chong was centering her own grief.

Writing about grief can be difficult, and building an exhibition on the subject is an even greater challenge. The labor involved in taking something as intangible and variable as grief and making it formal, structured, and accessible is astounding. As a poet and writer, I am sometimes challenged by the failures of language to adequately describe an experience. In Chong’s work, there is clarity in her process.

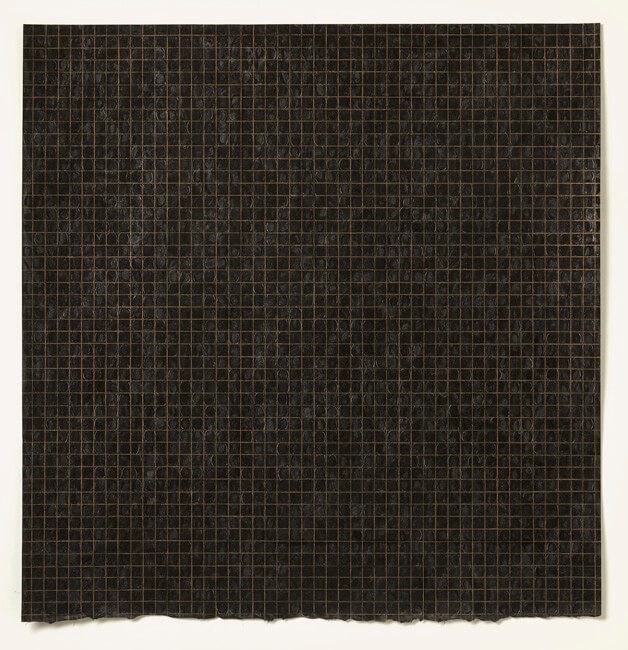

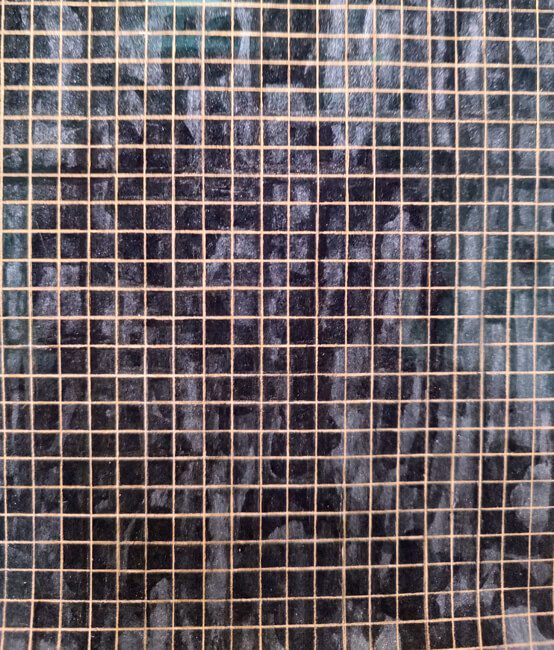

The exhibition by the New York City artist contained eleven works on handmade rice paper saturated with black gouache, powdered with mineral dust, then dried and ironed. Each work has uniform grid lines drawn with a copper colored pencil. I surprised myself getting lost in the endless rehearsal of it. My presence in the space was both conflicted and comforted. I recognized the privacy involved in the work, which made my presence in the gallery feel like an intrusion, but the gravity of the work offered solace, a place to dwell.

At one point, Rilke’s words circled around my head:

Even when the lights go out, even when someone

Says to me: “It’s over—,” even when from the stage

a gray gust of emptiness drifts toward me,

even when not one silent ancestor

sits beside me anymore…

I’ll sit here anyway. One can always watch

From a distance, it could’ve been easy to walk by the works—black squares on a white wall— but the work was revelatory up close. The black grid swallowed my shadow and I could only see the silhouette of my head if I moved; otherwise, I became lost in it, unable to see anything but the dizzying factory of the grid. There were curious white marks resembling parenthesis inside of the grid. Sometimes these chalk-like marks transformed—I’d see a bird or a nest and then it all disappeared, much like the metaphoric birds in Rilke’s second elegy:

Every angel is terrifying. And yet, alas,

I sing to you, almost fatal birds of the soul…

I suppose grief operates this way, sudden and repetitive, both familiar and unpredictable.

I spent a while debating with myself whether Chong’s work was a practice on revision or measuring absence. Or maybe they aren’t parentheses at all— maybe they’re tallies, maybe the marks are a way to meditate or pray. Rilke’s words reached me again:

Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angelic Orders?

It wasn’t long before I began placing myself in the artist’s shoes, much like Chong had put her own in Rilke’s. Arranged at eye level, the artwork offered a room, one that presented itself suddenly and one that I deeply contemplated. Grief, with all of its weight and reminders, is a universal experience and with the pendulum state of the world, wildly and widely sustaining. Chong’s exhibition offers a way to cope, to control what we can. I was seated in what she made of her experience and by doing so, driven to discover a way to document mine.

Chong’s exhibition was a testament to the ordinary labors and self-consumptions of grief. It felt good to experience the work. Good not as in happy, but as productive. The instinct of repositioning grief—coupled with the process of moving and acknowledging it—helps us gain the collective power to settle it.

I am reminded of art’s ability to reveal, as moving through and toward possibilities. Grief, to borrow Rilke’s words, is:

forever repositioned

on the scales of a wavering equipoise,

a public thing among shoulders.