Santa Fe-based George Alexander (Muscogee-Creek) explores contemporary Indigenous culture with imagery that challenges the boundaries of what is considered “Native art.”

Ofuskie, the studio of George Alexander, a Muscogee (Creek) Nation citizen, is nestled in the heart of the plaza in downtown Santa Fe on San Francisco Street, a road full of boutiques, restaurants, and art galleries. The Santa Fe Plaza receives heavy foot traffic from tourists and locals year-round, which means Alexander’s studio is centered in a rich mosaic of diverse people from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds in an artistic setting.

“It was always a dream of mine to have a studio in the plaza, so I made it very clear to myself that I wasn’t going to settle for anything less,” says Alexander, who also goes by Ofuskie.

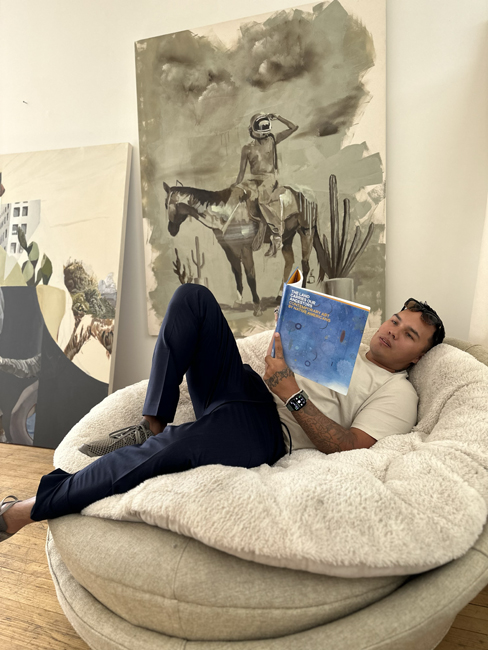

Walking into Ofuskie on a sunny September 2023 afternoon, I feel the warmth, comfort, and serenity of a well-lit artistic ambiance. Natural light pours through sheen curtains, creating a soothing yet exciting effect.

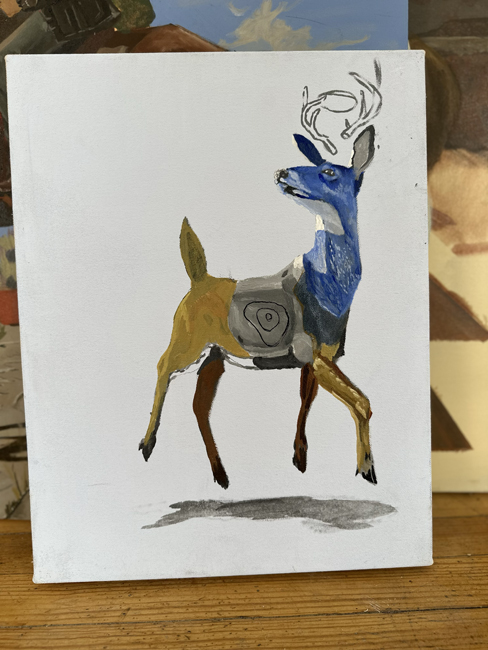

The space contains paintings in various stages of completion. A large canvas, lying on the wooden floor beneath a wooden frame, is ready to be stretched. Several paintings on easels have subtle earth tones. Other paintings are mounted on the wall while several artworks rest on the floor. Buckets of white gesso sit on a worktable.

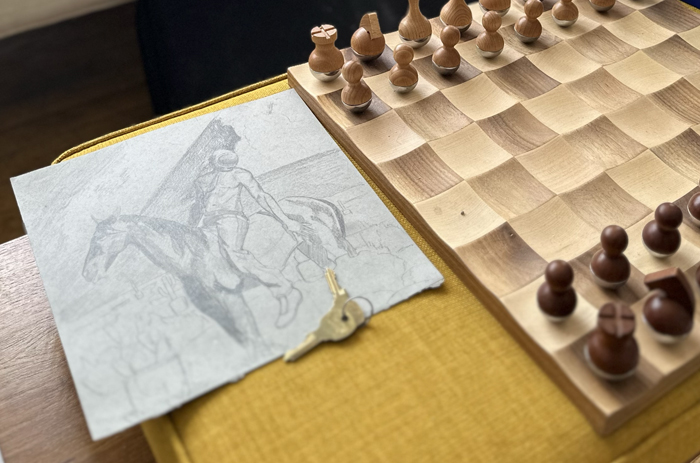

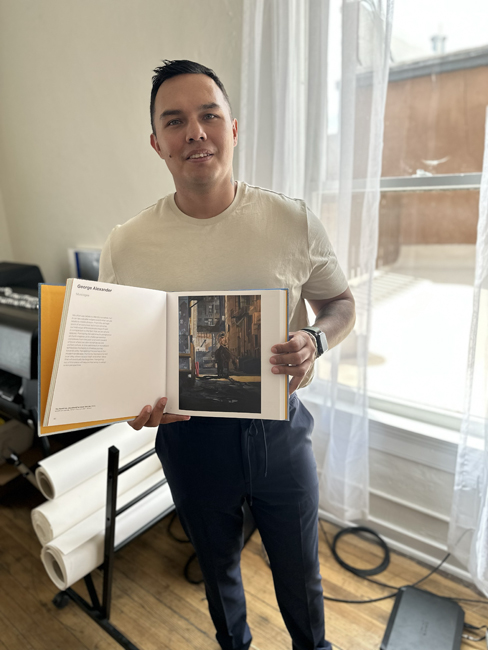

In his studio, a large circular chair with a puffy white cushion and a long beige couch in front of several windows provides the space for the interview, where Alexander expresses excitement about the arrival of the catalogue for The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans, an exhibition curated by noted artist Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith (Salish and Kootenai) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Alexander’s acrylic painting You found me, you should’ve never lost me—which depicts a shirtless figure wearing an astronaut helmet on horseback in what appears to be a city alleyway—is featured in the catalogue and exhibition that showcases works from nearly fifty Indigenous artists.

Alexander grew up in Mason, Oklahoma, a small rural community located within the Muscogee Creek Nation’s land. His Muscogee heritage and the landscapes of Oklahoma influence his paintings. He also draws inspiration from the flat style painting created by Indigenous artists in the early 20th century, such as Woody Crumbo (Potawatomi), Acee Blue Eagle (Muscogee), and Jerome Tiger (Muscogee Nation-Seminole). Oklahoma continues to be a hub for prolific Native artists including Dolores Purdy (Caddo Nation) and Virginia Stroud (Cherokee-Muscogee Creek), who work in a similar artistic style, in addition to many other modes and mediums.

During his adolescence, Alexander became fond of drawing—he recalls sketching his favorite cartoon characters with his cousins in the back rows of the Indian Baptist Church he and his family attended. His passion for drawing continued into high school. Graffiti and street art also inspired his artistic creativity—he drew script and used his desk as a canvas for his drawings. He even dabbled in tattooing.

After high school, Alexander graduated in 2015 with a bachelor’s degree in art from the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, where he received mentorship from the renowned artist Tony Abeyta (Navajo), who taught at IAIA at the time. Abeyta opened his studio to Alexander, allowing him to paint in a nurturing, professional environment. Alexander says that Abeyta’s guidance allowed him to learn a lot about navigating the art world. Abeyta also encouraged him to study painting abroad in Florence, Italy, where Alexander earned an MFA from Studio Arts College International in 2019.

Life experiences and humanitarian concerns have shaped the themes and imagery of Alexander’s paintings. At IAIA in his senior year, after watching the movie Interstellar, he felt challenged to paint an astronaut. Before purchasing an astronaut’s helmet on eBay, he turned to the internet to find images for visual reference.

Reflecting humorously on that pivotal time, he says, “I didn’t have enough money for an astronaut suit, so I put the astronaut helmet on my friends, and they would wear their everyday clothes and that became this cool metaphor. Having the perspective of an astronaut in outer space,” he continues, “means you see everything as a whole, there are no borders, no race, governments, politics, and you cannot see any of that. By putting the astronaut helmet on the person, it blurs their identity, and you are no longer focused on who the individual is but what the individual is about and where they are going.”

Several acrylic paintings feature his noted astronaut bare-chested on horseback. He attributes the mounted astronaut to the influences of Southwestern paintings, Indigenous symbolism, and popular culture. “What I’ve collected from this metaphor [of the mounted astronaut] is that humanity is on this timeless journey to find connectivity and a unified identity that speaks for all humanity,” he says. His astronaut series is sought by collectors and museums alike.

In his newest series, he uses a neo-surrealist approach. “The beauty of surrealism,” he states, “is that it’s dialogue within our own societies today. It’s looking at others’ way of thinking.”

His paintings in this genre contain flat-style elements and abstract backgrounds. He says that this method enables him to “represent an earlier time within contemporary Native art. This series has become more of a self-portrait than anything else.”

Reflecting on the potential success of an in-the-works painting at his studio, he declares, “You win some you lose some.” The imagery in the work in progress is personal to Alexander because it reflects himself and those closest to him such as his sister and late father. “The buck represents my dad, the astronaut helmet represents me, and the blackjack cards are in reference to my childhood. My sister was a blackjack dealer after my parents passed away. This is how my sister supported us.”

Because of the growing body of his innovative paintings with rich symbolism and aesthetic design from an Indigenous vantage point, there is much anticipation about what will come next for Alexander.