Eleven young Phoenix artists explore personal trauma, marginalized communities, environmental degradation, and other markers of contemporary society at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art.

SCOTTSDALE, AZ—A pile of hair appliances sits near the center of a gallery inside the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, symbolizing discarded perceptions of beauty that once led Mia B. Adams, a Black Latinx artist based in Phoenix, to straighten her hair.

The tangled heap of hair straighteners also signals something else: the ways in which so many young artists working in the desert Southwest are countering ideas and expectations at the heart of personal and collective traumas.

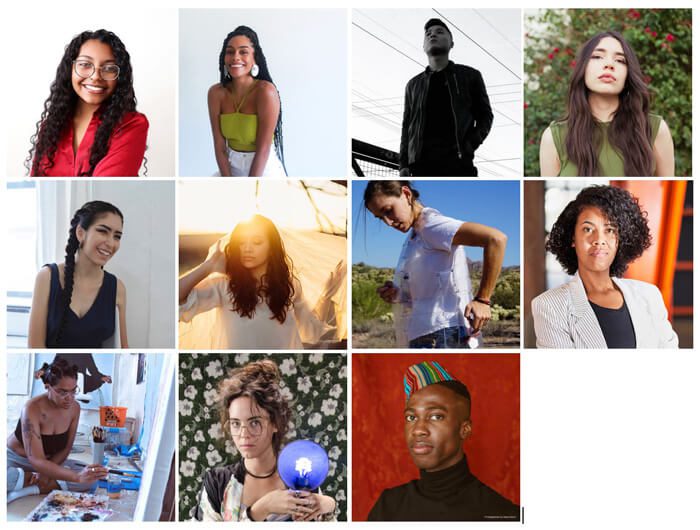

Adams is one of eleven artists featured in Forever Becoming: Young Phoenix Artists, an exhibition that opened September 11, 2021, and continues through January 23, 2022.

Lauren O’Connell put the exhibition together, along with Keshia Turley. O’Connell is the curator of contemporary art at SMoCA and Turley is the museum’s curatorial assistant.

Forever Becoming includes all new works created primarily by artists under the age of thirty. Featured artists explore personal trauma, marginalized communities, environmental degradation, and other markers of contemporary society.

Like Adams, many have something to discard.

For Lily Reeves, it’s the stress experienced during a year of quarantine marked by social and political upheaval. For Sam Frésquez, it’s the dominance of heteronormative imagery in visual culture.

Reeves’s Room to Breathe with two-channel video, neon light, and meditative sofa creates a space for viewers to find solace. Frésquez’s video The Meet Cute comprises scenes from iconic romantic comedies that have been altered using green screens—the artist replaces each male love interest with her own body, thus centering queer love.

Artists featured in Forever Becoming created their works with a fascinating array of materials.

Vincent Chung stitched together pieces of canvas, marking them with materials such as acrylic, oil stick, and spray paint plus layering in neon compositions. Merryn Omotayo Alaka used pony beads and synthetic hair to create a tapestry-like sculpture. Cydnei Mallory connected six large pillars of dark wood with T-shirt rope, signaling a communal family united in protecting BIPOC bodies.

“To me, these artists all have something in common,” O’Connell says of those she selected for the exhibition. “They’re all talking about transformation.”

All eleven are millennials, who sometimes get a bad rap. But O’Connell has a different perspective.

“These are the idealistic reformers who are really pushing it forward. They’re the ones who’ll be making changes coming into their own power,” she says. “There’s something really hopeful yet poignant about their work.”

For several of these artists, the geography and culture of the desert Southwest serve as compelling source material.

Lena Klett combined drawing and sculpture to deconstruct digital images and suggest alternative views of the natural world, while Steffi Faircloth and Estephania González created videos with performative elements.

Faircloth used ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response), an approach prevalent in YouTube videos, to assume the role of a hairstylist while considering her own experience of living in the borderlands. González cast herself as a celestial being in a two-channel video exploring the relationship of humans, nature, and the cosmos.

Papay Solomon and Brianna Noble channel their personal experiences to explore issues of identity through portraiture. Each artist questions traditional views of power and value while seeking to shift perspectives and embrace futurity through oil paintings on canvas. Noble painted herself in multiple settings; Solomon painted two perspectives of a single subject, a friend and fellow immigrant.

Turns out, these artists aren’t the only ones seeking transformation.

By highlighting young contemporary artists working in Arizona, O’Connell is hoping to transform perceptions about the region.

“A lot of people outside the area see the Southwest, especially Arizona, as a good old boy state or they romanticize the desert, marveling that the light is so pretty,” she says. “People see it as a very white, gun-toting place in some ways, but I’m excited to show that the region is home to a mix of people from all different backgrounds.”

For O’Connell, it’s an important time to highlight artists based in Phoenix, which is now the country’s fifth largest metropolis. “I’ve seen a lot of moves lately away from focusing on art in city centers like New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, and I’ve observed that the artists’ work here is on the level of what’s happening elsewhere.”

With Forever Becoming, she hopes to introduce these artists to new audiences both within the region and far beyond it. But she’s also honoring the decision they’ve made to stay in Phoenix. “I asked a lot of them why, and many said it was because they feel a sense of community or feel energized here.”

Training a critical eye on these pieces on view at Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, a final sentiment shared by O’Connell comes clearly into focus: “Phoenix is a place of possibility.”