Arizona artists Merryn Omotayo Alaka and Sam Fresquez incorporate unconventional materials including synthetic hair to explore identity and culture at Phoenix’s Lisa Sette Gallery.

PHOENIX, AZ—Sculptural chandeliers created with shimmering synthetic hair and fillagree braid clamps. A tire with tread covered in bright yellow patterns. An oversize hoop earring crafted of Brazilian gold granite often sourced for monuments and gravestones.

These are engaging pieces by emerging artists Merryn Omotayo Alaka and Sam Fresquez, whose explorations of culture and identity are part of Things We Carry, an exhibition that continues through September 25, 2021, at Lisa Sette Gallery in Phoenix (210 East Catalina Drive).

“This work is a quiet visual language,” explains Alaka. “It’s a metaphor for ourselves.”

They’ve been collaborating for five years, manifesting common threads in their experiences as women of color. Alaka draws on her identity as a mixed-race Black woman and Fresquez on her Latinx identity. Both identify as queer, which adds additional layers to their considerations of individual and collective traumas both evident and unseen.

The hand-carved Goodyear tire that visually confronts viewers as they enter the gallery, Fresquez’s Second Place is the First Loser (2021), hints at the compelling complexities and contradictions woven throughout this exhibition, which also includes works by Angela Ellsworth.

Fresquez grew up attending NASCAR races, where she remembers her father punctuating their presence on ancestral lands by pointing out various historical markers. “There’s such a deep-rooted history of racism and white supremacy in NASCAR,” she says. “The culture is so harmful, but it’s also a way that families spend time together.”

With Second Place is the First Loser, Fresquez also explores ideas about gender. “I was thinking about Mexican soccer player Jorge Campos, who wears bright patterns and colors,” she recalls of conceiving the colorful, carved tire. “Sports and cars are a performance of race and gender.”

Questions related to gender and race recur throughout their larger body of collaborative work, including the installation series It’s Mine, I Bought It. The title nods to rapper Princess Nokia’s song “Mine,” which calls out intrusive interrogations about Black hair.

Here, they’re showing works gallerist Lisa Sette describes as “floor-length suspensions of synthetic hair, each meticulously gathered into tassel, bubble, and chandelier forms.” Sometimes the hair is black or deep blue. Other times, the artists use white hair to symbolize knowledge and wisdom accrued over time and to counter narratives that align beauty with youth.

Both Alaka and Fresquez cite hairstyling rituals and expectations as central factors in the ongoing formation and expression of their own identities, which helps explain why these works hold such power.

“I have a lot of hair trauma,” says Alaka.

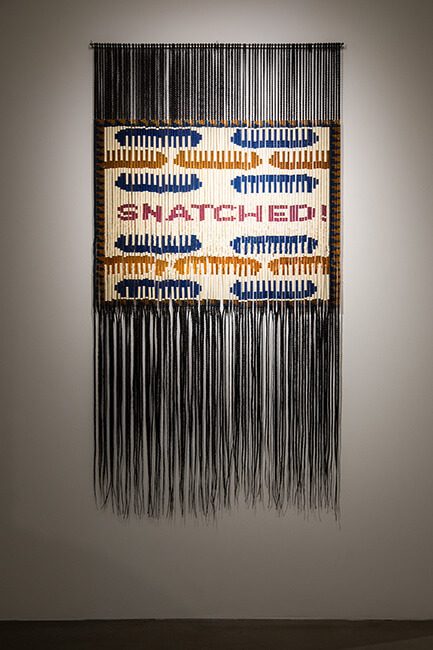

Hence, her 2021 work titled Snatched!, created with braided synthetic hair and pony beads. The word “SNATCHED!” appears at the center of the piece, surrounded by combs facing in alternating directions. The text has dual meanings, according to Alaka. “Snatched is slang for looking really good, or it can refer to someone pulling your hair out.”

Alaka says the pony beads, often used for braids and cornrows, channel the ways hair connects women of color to their ancestors. “Functionally the beads protect the fragile structure of Black hair,” she explains. “I see them as a metaphor for the ways I protect myself from the traumas I face.”

The exhibition also includes digital prints on linen that reflect the artists’ facility for storytelling and autobiography through patterns. Using repeated imagery and colors from one particular brand of eyebrow shaper, for example, they speak to societal and cultural definitions of beauty—and the artists’ first memories of being told to shave and wax their bodies.

Their oversize bamboo-design hoop earring (Remy Co. Door Knockers 1, 2021), titled after a local beauty supply store, considers how individuals and communities assign meaning and value. “We chose the hoop because we felt this object encapsulated Black and Brown people,” says Fresquez.

“We wondered what it would look like to build monuments for ourselves and our communities, and we wanted to counter the idea that white beauty is the standard,” she adds.

That’s just what they’ve done throughout the gallery, in part by using scale to create a strong visual presence that counters the invisibility of women of color in public spaces.

It’s most evident in Double Take and Notorious W I G, two works from 2021 that serve as stand-ins for the artists’ own bodies. For the latter, they drew inspiration from a wig used by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City to display hair clamps found inside an ancient Egyptian tomb.

“This feels like a reclaiming of power after someone has taken something away from you,” says Alaka. “Instead of shrinking into ourselves, we’re showing that we deserve to take up space.”