In the first exhibition to explore Harry Fonseca’s expressions of “queerness” through his beloved character Coyote, queer-Indigenous performativity takes center stage.

Harry Fonseca: Transformations

May 3, 2024–March 20, 2025

Heard Museum, Phoenix

In 1972, Harry Fonseca (Nisenan Maidu/Native Hawaiian/Portuguese, 1946-2006) witnessed the Maidu Oleil (Coyote) dance. That ritual awakening, along with learning his uncle’s Maidu practices and Coyote stories, transported Fonseca and his artistic practice into new realms “feral with possibility.” Such was the power of Coyote for Fonseca, according to information accompanying the small but insightful exhibition Harry Fonseca: Transformations, on view through March 20, 2025, at the Heard Museum in Phoenix. “Coyote is portrayed as [a] fallible, wily, arrogant, yet adaptable figure with racy humor,” reads a wall panel. “[F]or Fonseca, Coyote was unleashed to explore the ordinary and liberated imagined spaces in affirmation of his own kaleidoscopic identity.”

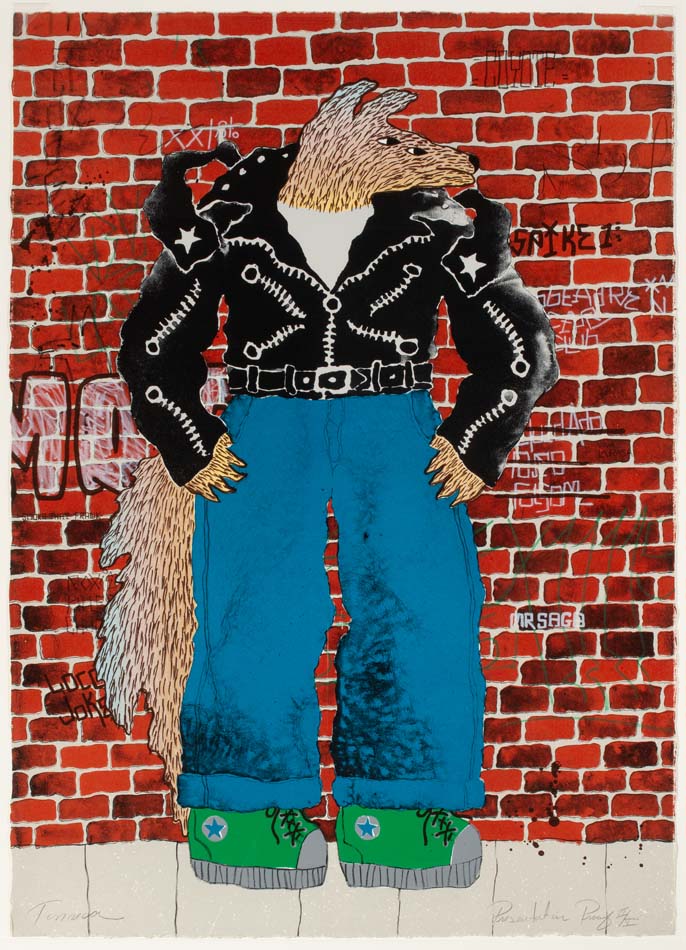

Fonseca began his Coyote series in 1979, and the identity presented in these works explores vivid performativity of queerness and Indigeneity, particularly within the safe confines of gay culture and its venues. The lithograph Coyote in the Mission (1983), i.e., the Mission District of San Francisco, establishes Fonseca and his alter ego’s bonafides with Coyote dressed in white t-shirt, denim jeans, and a black leather jacket festooned with silver zippers and stars as he relaxes against a brick wall tagged with references to SOMA, or South of Market, an area known for its queer leather communities.

Coyote keeps the leather jacket “onstage” in the mixed-media piece Roxie – The Black Swan (1984) while partnering a female Coyote (Roxie) in black tutu and pointe shoes. He jetés in front of footlights across a checkerboard floor, giving Roxie a sly look as a windowed ballerina dramatically flexes her wrist to drop her hand over her face. Framed in red velvet curtains tasseled in gold, the piece brilliantly ensconces queer and Indigenous performance, and queer-Indigenous performance, in the realm of European high art—with tongue firmly in cheek.

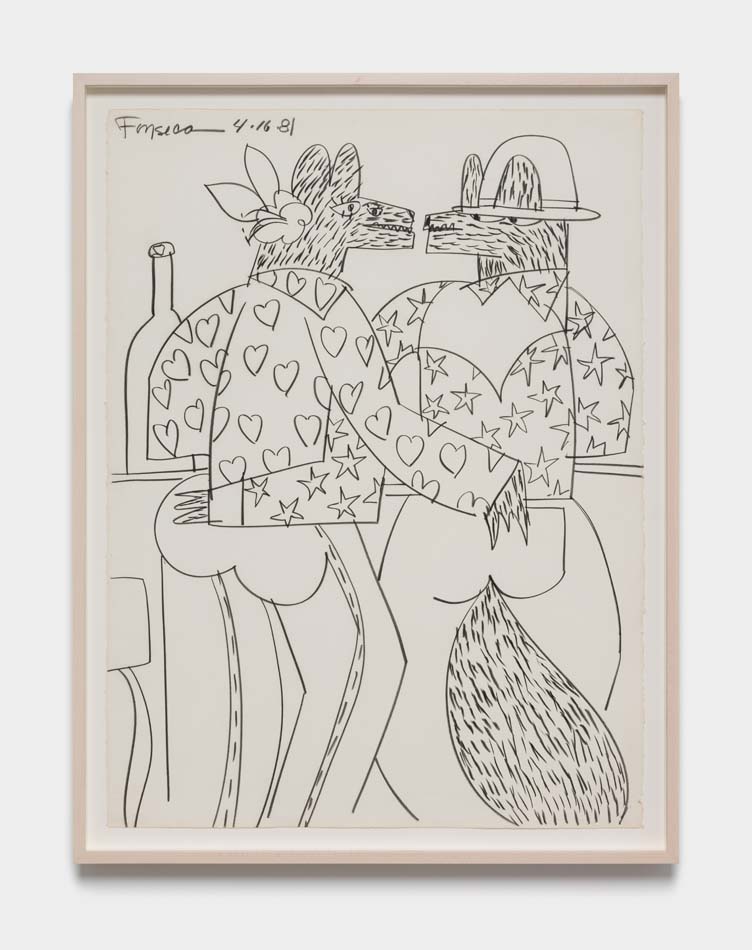

Among the Maidu, Coyote benevolently teaches his people the wholeness of human nature. Fonseca’s black-and-gray pen, ink, and watercolor images on paper truly express Coyote’s freedoms and grace. Representational in form yet abstract in energy and execution, these pieces from the 1980s animate Coyote with a cartoon-like eloquence. Holding dance sticks, with barely contained energy burgeoning out their bushy tails from the confines of finely drawn lines, the slim figures bloom with an embodied life force. These figures are content, looking deep within themselves and their joy. In Fonseca’s other works in the exhibition, Coyote’s open eyes are placed together on one side, giving males and females a sly, side-eye visage. They’re also more substantial, bulky, and burly, with tails to match.

The compact exhibition, which also includes artwork Fonseca provided to the National Native American AIDS Prevention Center for catalogues, explores its topic incisively and thoroughly, encapsulating a world of intertwined identities that Fonseca lived and enlivened through his art.