Fiction

Empty Set

by Verónica Gerber Bicecci

translated by Christina Macsweeney

Coffee House Press (February 6, 2018)

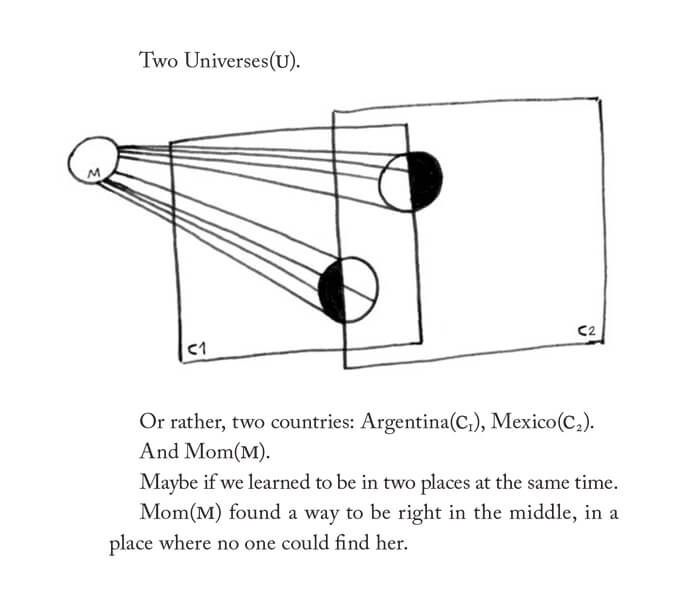

Calling herself a “visual artist who writes,” author Verónica Gerber Bicecci approaches fiction from the conceptual and the personal simultaneously: what does it mean, logically, for a person to be missing? And how does it feel? Bicecci incorporates line drawings throughout Empty Set, her novel in fragments, which serve as diagrams of how the characters relate to one another. Her missing mother is a vector (M) beyond the two planes of Argentina (C1) and Mexico (C2), which comprise the narrator’s Universes (U). Or the narrator’s breakup appears as a series of Venn diagrams, eventually leaving one circle (I) with a bite taken out. The narrator moves into her mother’s now empty apartment and begins to patch its soft, caving-in walls with plywood boards that she paints obsessively, following only the lines in the grains of wood. Dendrochronology, the study of tree rings, is just one of the intellectual gambits that orbit the novel, returning and returning as the narrator examines each of her own empty sets—her relationships and her losses.

Quote:

Wonder what my life would look like inside a tree trunk, what all those lines, knots, and circumferences would mean. Wonder how a set of truncated outsets, an abrupt ending, or a disappearance would be written in that language.

Nonfiction

Heart Berries

by Terese Mailhot

Counterpoint (February 6, 2018)

IAIA Low Res MFA graduate Terese Mailhot began her memoir as fiction, but a realization about abuse in her childhood warped the project into nonfiction. I struggled with my reading of Heart Berries: against its at times obscured movement between sentences, its searing emotional heat, its insistence that the narrator’s painful life be not just witnessed but felt. Teaching nonfiction to undergraduate writers at IAIA, I struggled, too, with the familiarity of her subjects: physical, sexual, and emotional abuse by parents and friends; ever-present alcoholism; poverty; and ongoing racism and invisibility. These are experiences that my students, often still in their teens, are trying to render on the page, and Mailhot’s story hits so close to home. As I read, comparisons popped out to me at random: Claire Vaye Watkins’ Battleborn in its dealing with ugly and well known family history, Natalie Eilbert’s Indictus for giving a name to past abuses, and Tommy Pico’s Nature Poem which, like Heart Berries, works against a series of stereotypes about indigenous people and their writing by naming those tropes directly. The difficulty of her subjects and her language, I realized by the end of a brief but mighty 140 pages, stems directly from the amount of reckoning she has set out to do, and the near-impossibility of finding language for that reckoning.

Quote:

His smell was not monstrous, nor the crooks of his body. The invasive thought that he died alone in a hotel room is too much. It is dangerous to think about him, as it was dangerous to have him as my father, as it is dangerous to mourn someone I fear becoming.

Poetry

The Möbius Strip Club of Grief

by Bianca Stone

Tin House (February 27, 2018)

Inside the Mobius strip club of grief, “all the drinks are free. Grocery store rosé in gallon / bottles on every table. And the dead don’t want your tips. They just / want you to listen to their poems. Don’t do anything dangerous. / And call every once in a while.” Rarely, if ever, do I read a book that is clearly the author’s confrontation with the death of a loved one—Stone’s mother—and find myself belly laughing. Aiming right for the heart where the piety of grief meets the ghastliness of death, Stone lays bare the out-and-out greed of the living. Now that the dead are gone and can ask nothing of us, we ask ceaselessly of them: that they comfort us, keep us safe, reassure us about our choices and our beliefs. In the strip club, Stone’s inferno, the dead charge for their exploitation. “$20 for five minutes; / I’ll hold your hand in my own. I’ll tell you / you were good to me.” Stone’s poems find the humor in pain, the sex in disgust, the lust in loss. I never quite know where she’s going at the outset of a poem, like “Making Applesauce with My Dead Grandmother”: “I dig her up and plop her down in a wicker chair. / She’s going to make applesauce and I’m going to get drunk.” But by the last lines of each poem, I am both cringing and embraced in recognition.

Quote:

Off-hours, the dead wait at the center of the room, sitting

Backward in chairs,

lounging in nipple-tassels,

reading goodbye letters that’d been tucked into their caskets.