Esther Elia: Diasporic Deities reimagines ancient Assyrian goddesses with attention to how they have evolved apace with their peoples, who are now distributed throughout the globe.

Esther Elia: Diasporic Deities

February 3–24, 2023

Sanitary Tortilla Factory, Albuquerque

Esther Elia’s work asks us to consider our notions of safety and—as is written in the interpretive sign that welcomes viewers to her solo show Alaha d’Galoota or Diasporic Deities—to remember the moments when we have felt most strong. In exploring safety and strength, Elia has created it—a sanctuary in downtown Albuquerque at Sanitary Tortilla Factory. As the gallery’s large metal doors swing shut and the outside world is hushed, we enter a temple occupied by bodybuilders and shadows, a pantheon of old goddesses revived for a new world.

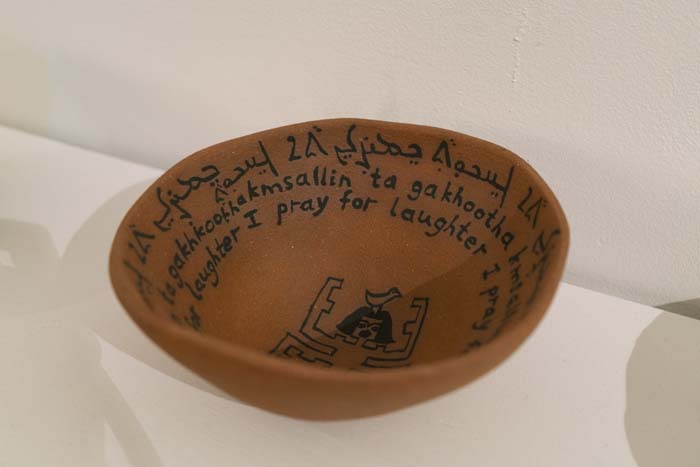

The work in Diasporic Deities includes canvas banners painted in acrylic, eight-foot-tall tiled sculptures, clay prayer bowls, and a painted canvas dress. Spatially, the two large-scale sculptures dominate (Miztanta Deity and Malikta Deity, both 2022), but there remains enough breathing room to notice the details—a disco ball-esque camel hanging from the ceiling, a small wooden talisman near the front door, or the inscription “I pray for laughter” etched in the bottom of a clay vessel.

Elia is Assyrian, an ethnic and religious minority whose homelands cross modern-day Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. In the aftermath of genocides throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, Assyrians today are dispersed throughout the globe. Through her work, Elia investigates the experience of her culture as it evolves in new places while recognizing “the difficult dance of diaspora,” as she writes, and that “not all change is assimilation—some of it is growth.”

So these goddesses are not like their ancient forebears, reliefs in stone or alabaster, yet are summoned from similarly age-old practices (the gridded figures in rug weaving, for example). But these goddesses sport boots, large biceps, and bikinis. They are mighty, winged, and bring assurance and protection to the children of the Assyrian diaspora.

Take for example, Bodybuilder Deities in the Garden (2022), a five-foot acrylic painting in which twin, many-limbed goddesses hover over palmy growth. They are both exalted and earthy—toeing a line between very human stoicism and the totally transcendent. Maybe it is human nature to look for the immortal in the world around us, to conjure a face to put on all that transcends us. But to do so as Elia has here—not with eyes fixed on the past, but with attention to how these goddesses have endured, accompanying their people through centuries and across oceans—draws them in closer. If they are here, it must be out of love. They have traveled, they have changed, they have lifted weights. Elia’s protective talismans are not made in deference to human fears, but with respect and attention to something more eternal—change.