Emily Margarit Mason challenges the limits of the still image by placing photos into alternative settings—whether baking one into a cake or rearranging another into an abstract collage.

Emily Margarit Mason opens the door to her studio, a warehouse-like space with high ceilings and a skylight. Most buildings in Santa Fe have low ceilings, so you notice when you walk into a room with space overhead.

Fragments of photographs lie near viewfinders, tiny Polaroids documenting variations of a recent piece, found objects—a long white snakeskin, a near-perfect-spiral shell, several rocks, smooth and rough branches.

Emily has loosely taped the top two corners of several large prints to a white wall. Others bend against it, lie piled on a work table, or are layered on the floor. She raises the bottom of a print from the wall, allows it to fall back, shifts an image on the floor diagonally, then straightens it. Her studio has a moving, generative quality—past art mingled with and informing current projects, each stage emerging from the last.

Emily lifts a piece from ten years ago when she began to think of ways to extend a photo past a single moment in time and space. What if you bring a photo back into the environment that created it? If you allow it to interact with that environment?

To explore these questions, she removed family photographs from frames and albums and placed them back into the world of her experience. Based on memories she associated with the photos, she developed unique processes for them—she baked one into a cake, boiled another in saltwater, and buried a third. Then, she retrieved the altered images and cast them in resin.

I think of how trees use resin. When bark is damaged by insects, resin covers the harmed areas, and forms a seal. Memories harden around damaged images in a similar way. By making that hardening visible, the series suggests the frailty of the image it encloses.

In the moment, I simply notice the resin block’s weight in my palm, its roughness.

Our conversation returns to light several times—the lingering blue hour after sunset at White Sands, watching the cloud shadows move over a mountain, the way light alters the shape of the datura flower (which blooms at night), how light looks across moving water at different times of day, through wet panes of glass, reflective plastic, different lenses. Its mutability, a word I also associate with her recent work.

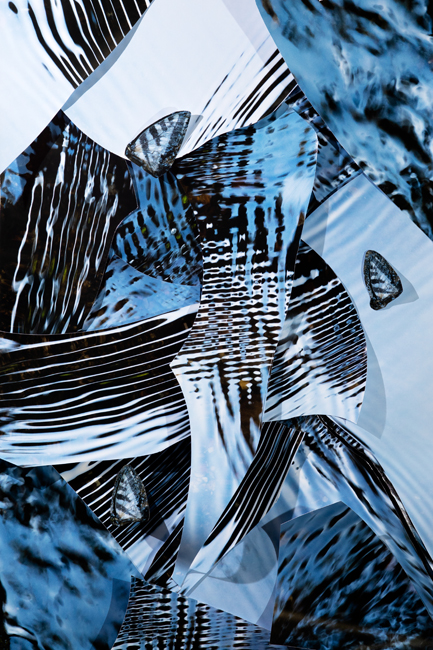

Emily often cuts her photos into fragments, arranges the pieces into abstract collages, and rephotographs them. At first, the subsequent images appear unrecognizable, but gradually, familiar textures and colors emerge.

I lean closer to one called Butterfly Wings in a River. At a glance, I see shades of blue. Brushmarks—no, ripples across water. A tremor-like ripple and an expanding one. Fragments layered on top of each another like strokes. The muscularity of a current coming from several directions at once. Three delicate blue butterflies.

The image makes me wonder if I know anything well enough to recognize it rearranged. How much sequence matters to understanding. How openly we see before we define what we see.

I close my eyes and attempt to recall the photo. I think of the difference between a raindrop on dry skin and a raindrop on wet skin. I try to remember the delicacy of water alongside the frailty of wings—why is it easier to sympathize with something that might falter? What is the word for the impulse to create a story from a fragment of blue?

When I arrive home, I flip through Sea and Fog by artist and poet Etel Adnan and come across a line that expresses my experience of Emily’s work: “A drop of water plus a drop of light have arrived before language.”