Ceramicist Elaine Parks, in the under-appreciated northern Nevada landscape, carefully combs the environment to find and fashion objects that command awareness and attention.

Ceramicist and sculptor Elaine Parks has lived in a town of fourteen million—and a town of fourteen. These differences in scale and perspective are key to her art practice, which stems from a keen attention to detail.

“I noticed a difference in how much people pay attention to the landscape,” Parks explains. “Los Angeles [Parks’s hometown] is surrounded by mountains, but people often don’t see them. In the desert, they do. It’s all a matter of attention.”

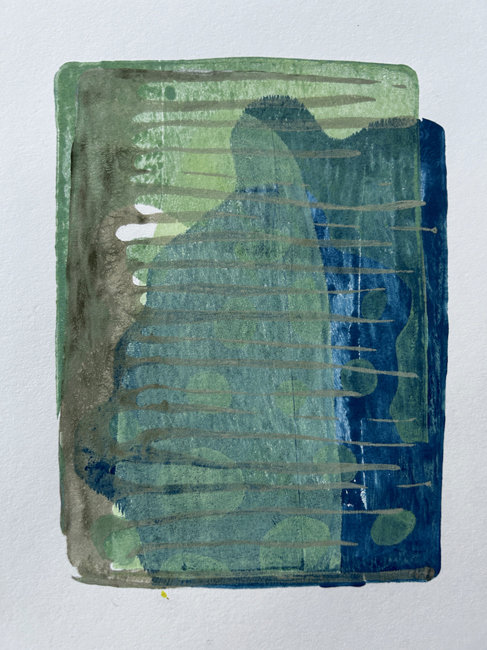

Parks’s discerning gaze and skilled hands turn elements of the desert landscape, and the objects it’s swallowed, into artifacts. Though she works across media, Parks most often uses clay in conjunction with found objects and textures to create sculptural pieces that emulate, but never mimic, the forms and features of the world around her. The results are quiet revelations on place and our relationship to it.

“You can see everything in the desert,” Parks says. “Nothing is obscured. In a forest, it’s harder to see everything. Treed environments hide that vastness, while desert environments reveal a lot. You can see far, you can think about going there. You can project yourself onto the land.”

Parks has spent a lot of time with the land. Since moving to Nevada after receiving her MFA from California State University, Los Angeles, she’s been based in Reno. But she has a studio and pottery school in Tuscarora, a town of ten-odd people at the northern edge of the Great Basin. Here, frequent desert walks are part of Parks’s art practice. She focuses on the details, using her phone’s camera to zoom in on textures that catch her eye. “There are so many fantastic textures, even in the same environment, the same rock, it blows you away,” she says.

Sometimes, she even picks up trash. “Wind will blow foam out into the desert and work on it so that it looks like rock,” she explains. “I’ll take it back to the studio, and it fools me for a minute—which I kind of like. It’s nice to look at the other side of something.”

This multiplicity of meaning within one form inspires much of Parks’s work. “There are things you can’t quite pin down with certain artifacts,” she says. ”It tells a story, but we don’t know what. There are archaeologists or paleontologists who make their life’s work finding out what that is. I am more interested in questions.”

Her objects invite us to steep in those questions and wade through all the possible stories. They are, on some level, impressionistic. They resemble biological forms—animals, bones, even cellular structures—but deviate slightly, frustrating tidy categorization.

“I avoid trying to copy nature because I’d fail at it,” Parks says with a dry chuckle. “What I’m trying to get is a similar sense. That leads me back to the artifact idea—the work is an artifact of my seeing or being out there. I want to recreate my feeling of seeing that interesting texture in a rock.” It’s about generating a feeling, not a taxonomy. Looking at Parks’s sculptures becomes a meditation on shape, color, texture—the intricate building blocks of the world around us.

Her latest body of work, Fossils and Bones, is on view as a solo show at the Northwest Reno Library through January 14, 2024. In the exhibition, rusty metal scrapped from the desert forms the base of bone stacks, surreal spines carved from clay.

“I like the idea of incorporating found objects,” Parks says of the way she combined desert detritus and ceramics in this work. “They bring a legitimate past into the piece.”

In other pieces, soft spheres form networks that resemble cells, or dew drops beading the surface of a leaf. The organic forms reflect Parks’s process of making them—“I’ll decide on a system, or a central form, and I’ll put them together and see what happens,” she explains. The goal is to make them look like they truly grew this way, one shaping seamlessly spawning the next.

The subtle deviations from reality across Parks’s pieces create a tension that simultaneously frustrates and fascinates viewers. “I’ve noticed people want to be specific,” Parks says of visitors’ reactions to the Reno show. “People want to assign a name to it. I think it might be human nature to want to pin down what that thing is, what it’s for, what it does,” she suggests.

But the work quietly defies that urge—“it’s slightly uncomfortable,” Parks acknowledges. The power of her attention is manifest in the uncanny qualities of her sculptures, the bones that aren’t quite bones. If initial recognition draws people in, then ambiguity makes them look a little longer.

Parks questions the political utility of her work, but does believe prolonged looking can be a profound act of witness. “Imposing something so big as a major environmental concern feels a little like a stretch,” she says, “but nature is very important to me. I wish nature were very important to everybody.” The double-takes her work prompt are a means of emphasis. “More awareness,” Parks declares, returning to the notion of attention. “Even in a city.”

Parks’s work will be on view in the group exhibition Earth and Ember at Cal State LA from January 22 to February 29, 2024.