Cruising down the packed blocks of downtown Los Angeles, where open-air storefronts advertising their services in Spanish face the amblers of the sidewalk, I am struck by how much this dense corridor reminds me of Mexico City. Indeed, perhaps the whole of the nation’s second biggest city—from its palm tree and cactus-lined boulevards to the dust-colored desert foothills (even when bedecked with the letters: HOLLYWOOD)—has more in common with the landscapes of Latin America than many other American hubs. It could be that the So Cal metropolis was still a part of Mexican territory when it was founded, or perhaps it is the city’s huge Latino community that lends the place its vibrancy today. In some respects, the LA art scene has more points of commonality with the southernly big cities of Latin America than, say, that of New York.

It makes sense then, that the Getty Foundation has pumped millions into funding Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, a massive series of exhibitions that puts the City of Angels in conversation with the artists of Latin America. Started nearly five years ago, there are now 70 Southern California art institutions that host PST exhibitions between the months of September and January, including a who’s who of renowned museums like the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), The Broad, the Getty Center, and The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, along with scads of other galleries throughout the southern expanse of the state.

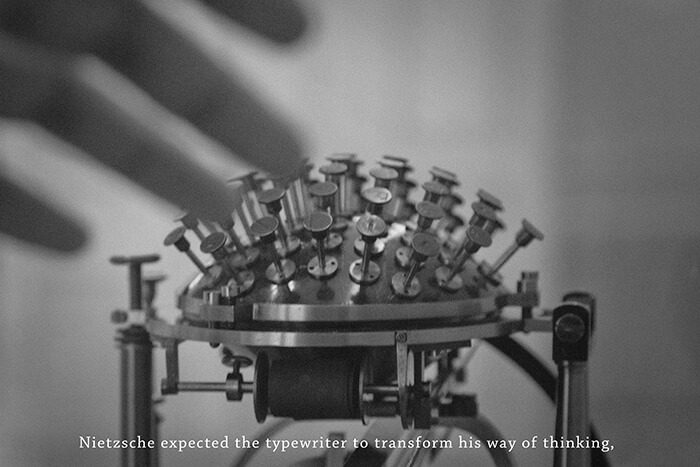

Perhaps the most literal evocation of the dialogue between these places is on display in A Universal History of Infamy at LACMA (August 20, 2017-February 19, 2018), an exhibition that takes its name from Jorge Luis Borges’s first printed collection of short stories. In this series of installations, Latin American artists collaborated with stateside Latino artists during residencies at the 18th Street Arts Center in Santa Monica. The resulting pieces break down topographies contingent on borders and instead emphasize the substance of shared realities and illuminate the complexity of the diaspora. Playing much like the fantastical tales of Borges, there are pieces like Ecuadorian artist Oscar Santillán’s Afterword, which documents German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s frustrations with the newly invented typewriter. Nietzsche believed the machine might make his words “dance,” but a malfunctioning part instead made them illegible. Santillán took a corner of one of Nietzsche’s typewriter throw-aways as an energy source for a psychic, who then brought the “dance” Nietzsche mentioned to the physical world for the first time. Documented with video of the psychic’s dance, framed prints of Nietzsche’s documents, and a short, explanatory film, Santillán’s work—like many in A Universal History of Infamy—breaks down and reimagines the languages in which we communicate and answers why we bother.

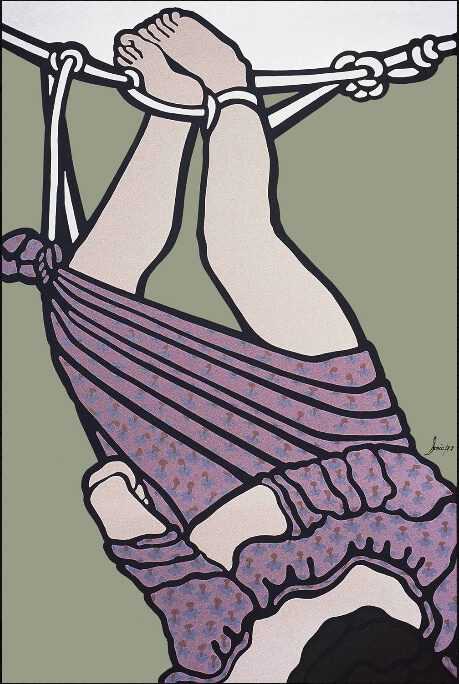

At the Hammer Museum, PST hones in on something more exact—the voices of progressive women through Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985 (September 15-December 31, 2017), an exhibition that finally acknowledges the voices of women in developing the artistic culture of Latin America and the United States, each of which has, in turn, inspired creatives the world over. The women of the 20th century produced impressive work long suppressed from the canonical lecterns of art historians, but here that work refreshingly takes up space. Heavy-hitters like Ana Mendieta are displayed alongside lesser-knowns like Sonia Gutiérrez, constituting the first exhibition of radical art practice exclusively by Latinas. To walk these rooms represents death to a gap in our understanding of the amelioration of contemporary art.

Examining space closer to our New Mexican home are the works currently on display at West LA’s Craft & Folk Art Museum in The US-Mexico Border: Place, Imagination, and Possibility (September 10-January 7, 2018). A locus of migration and political debate, the borderlands also reveal nuance in investigations of identity, physical place, and how those things can inform possibilities—both personal and comprehensive. Striking works that negotiate the divide include Ana Serrano’s Cartonlandia, which brings the layered architecture of many Latin American cities to this side of the border through repurposed, colorful cardboard collage. Others include such stark images as Pablo López Luz’s Tijuana-San Diego County III, Frontera USA-Mexico, an aerial photograph that documents the border wall and the blank sameness of the land on either side. These visceral, evocative works potently bring to bear the realities of space on both sides of the boundary in all their psychic and physical iterations.

New Mexico’s proximity to Los Angeles—and our own profound ties to Latin America—make the vast, diverse works of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA resonant and world-shaping. Locals can get a taste of the work without making the trip when The US-Mexico Border: Place, Imagination, and Possibility comes to 516 Arts (Albuquerque) and the Albuquerque Museum in late January. Until then, 800 miles away in Los Angeles, and worlds away in Latin America, voices are shaping new aesthetics and new dialogues that inform the mind and sharpen our eyes on the world.