Tya Alisa Anthony untangles the meaning of safe spaces as sanctuary and explores the art of social justice, human rights, and identity in the Mile High City.

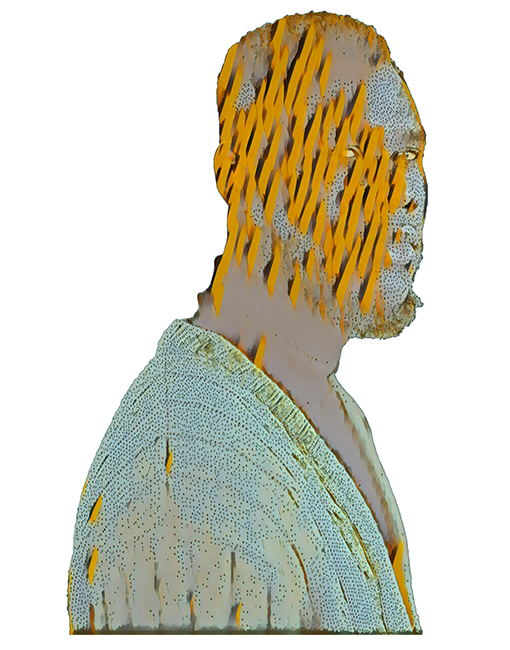

DENVER—Most of the subjects in Tya Alisa Anthony’s works have unfortunately experienced trauma and tragedy. While the Denver-based artist communicates specific concerns, like housing and equity for marginalized people, the underlying message is focused on the general disregard for people of color.

“I want to subvert thoughts around stereotypes and conflicted colonized margins of thought,” explains Anthony, who says that she concentrates on elevating her practice by “thinking about narrative and storytelling in a way that’s representative of my experience.”

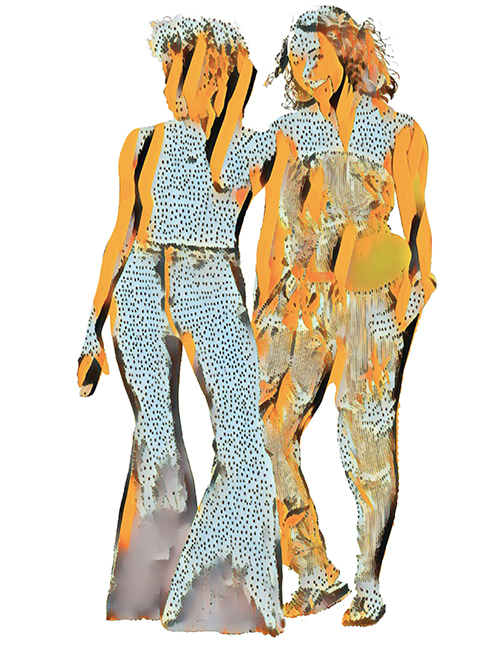

Anthony—an interdisciplinary artist, curator, researcher, and the new director of community education and outreach at RedLine Contemporary Art Center—reimagines histories and creates autonomous spaces for bodies of color through her photographic, collage, and sculptural works.

“I never necessarily felt like art was my calling. More so, it is advocacy, responsibility, and a duty to the communities I belong to,” says Anthony, whose work not only shapes a visual representation of her connectivity to her communities, but also showcases the roadmap of her lived experience with what we think, or consider to be, sanctuary or safety.

“My work has you deal with what happens in society, where I see myself, how we can move forward, and how we resist to understand history,” adds Anthony, who explores themes of social justice, human rights, and identity.

Anthony grew up in Baltimore, where she found herself exploring, as an artist and concerned citizen, the displacement of low-income families and families of color from the city’s thousands of row homes. “These houses are being torn down and turned into open spaces to be rebuilt or, most likely, renovated into spaces that the people who’ve lived there for decades can no longer afford,” she says.

“So many of these homes are condemned and falling apart to the point that trees are growing out of some of them,” adds Anthony, who sometimes incorporates moss into her works to illustrate the idea of nature taking over urban landscapes. She hopes to take a similar social and artistic approach when examining recent changes in her current hometown. “The landscape has abruptly changed here in Denver and not all landscapes look the same in everyone’s experience.”

Recently, Anthony explored the landscapes of local communities by melding interactive performance, photographic survey, and sculptural exploration in her solo exhibition Muscle Memory at Leon Gallery, a non-profit creative space dedicated to mentoring emerging artists across multiple disciplines. The show opened the door for the artist to further one-on-one discussions with the Denver community about several difficult topics, and sought to act as a salve for those grappling with pandemic upheaval, decaying underserved communities, civil unrest, police brutality against people of color, and the country’s broken carceral system.

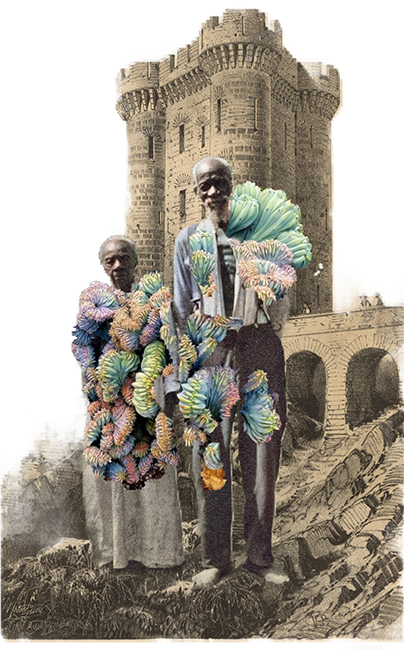

One of Anthony’s favorite exhibitions that she has displayed acted as a slightly less heavy, but just as robust, inspiriting of marginalized voices. For Organic Tarot, which exhibited earlier this year at the Denver Botanic Gardens, Anthony drew from archival historical photos of Black sharecroppers and former slaves, and infused the images with new life, thanks to vibrant botanical symbolism, gold painted embellishments, and the allure of tarot.

“I wanted to elevate [the subjects in the artworks] into a space where they had ownership where they possessed strength,” explains Anthony. “I’m telling a story about my experience and I see these ancestors as representations of what tarot is, the major arcana, the minor arcana, these archetypes, these situations, these explorations of the human experience… it was a peaceful, soft, warm, and inviting series that gave everyone an entry point into the human experience.”

Currently, Anthony is focused on her new role at RedLine, where she builds reciprocal relationships between artists and communities to create impactful and collaborative social change.

“I’m always thinking about social justice as a means of expression as the means of bringing community together as well as thinking of contemporary art as a vehicle to do so,” says Anthony, who has a body of work that permanently lives at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. She’s also a member of the Octopus Initiative, a collective of artists who lend their work, free of charge, to the MCA, which then allows any Denver metro area resident to apply to be chosen to borrow artworks for ten months.

Additionally, for the first time in a few years, she has been able to focus her artistic practice on researching redlining and scouring through historical legal documents—she hopes the scholarly data can enhance her new works. She says this approach allows her to “make art for catharsis and those that need it because I feel that there is still much to be learned and to be supported in the human condition.”

“Would I consider myself a political artist? I think being alive is political in the body that I possess,” Anthony says. “As a Black female mother of two [and a] married artist who’s breathing, that’s a political act every day.”