Debra Baxter has just chucked something across her studio. A five-pointed throwing star sticks firmly into the opposite wall. She’s about to throw another, but first she shows it to me. It’s elegant lace made of metal. The tips have been sharpened.

Baxter’s work occupies several unlikely but generative intersections: between the fierce and the sentimental, between museum pieces and ready-to-wear jewelry. Since her early pieces in alabaster, Baxter has tried to find a way to use sculpture to harness a woman’s voice, her source both of power and of vulnerability. By combining alabaster, metal, crystals, and found objects, Baxter’s sculptures seek to undermine the stereotypes of the feminine. Her breastplates cast the soft fabrics and decorative lace of the Victorian era into bronze. Playing with typically sentimental visual tropes that are often confined to the narrow definitions of the conventionally feminine or “ladylike,” Baxter’s attention to materials evokes a roughness more often associated with the physicality of male expressionist sculptors, such as David Smith or Rodin.

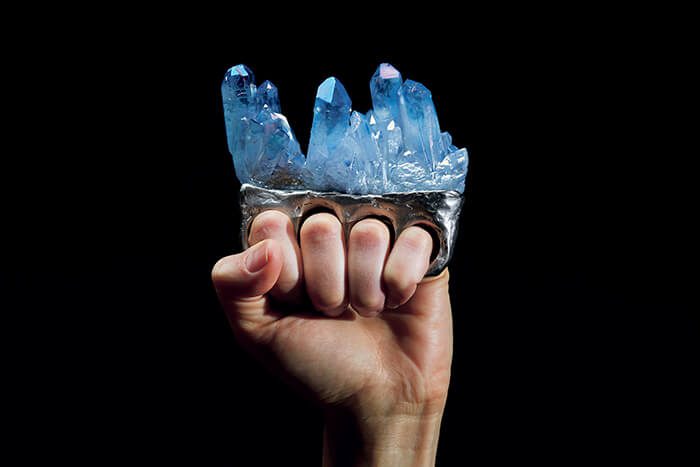

As a jewelry designer, Baxter brings weight and sharp angularity to a traditionally delicate craft. Her necklaces for her line, DB/CB, take the form of shaped metal vessels, somewhat like triangular bowls, to hold outsize coarse crystals. The protective qualities associated with crystals merge with the shielding of metallic armor. Her lace throwing stars, like her Devil Horns Crystal Brass Knuckles (Lefty) (2016), held in the Smithsonian’s permanent collection, ask what feminist weapons might look like and how women can feel not just safe but powerful in their art and in their daily lives.

Jenn Shapland: Tell me about the materials that you use.

Debra Baxter: What am I working with right now? Well, it’s never one thing. My thing is attaching materials that don’t make any sense together. I used to just carve alabaster, and then I got a little bored with that and started attaching things to the alabaster, going off into other crystals and materials. And the funny thing was, during this whole shift—maybe it was a post-grad school thing—I got an MFA at Bard—I was concerned my work was too pretty. At the time, in New York, what was happening was very conceptual, blobby work. One of my professors called it “slapdash.” It’d be a weird lump with, like, a wig on it with a piece of drywall. The works were really cool and interesting and super smart, but I kept going towards more classical and “beautiful” and sentimental, which is not super cool.

Have you moved in a different direction since your alabaster days?

Yes, but I still fight with myself about the pretty—being too pretty and being too traditional. Because I like some really out-there stuff: lumpy plaster and mixed found objects and things. But I keep coming back to metal and rock. The other material I’m really jazzed about right now is rawhide, like a dog’s chew toy. You can buy it in sheets. You put it in a bathtub, get it warm, and then you wrap it around whatever. And then you go and shape it and try to get it to stay that way, because it wants to go back to flat. At the Albuquerque Foundry, they’re doing an experiment for me to see if they can do a direct burn-out, and then that’ll be metal. The rawhide is just really beautiful, like a paper bag: papery, crunchy the more I mess with it. And I’ve been trying to figure out just what the heck to do with it.

It has a fabric quality almost.

I don’t know if you saw those “pillows” that are at form & concept. I’m interested in the history of drapery: in art history, and in drawing classes, and on the body. I’ve always found it very interesting. I used to teach drawing, and having students draw drapery is such a good way for them to learn value. When you shine a light on drapery, you get all the values. With the rawhide, I also wonder: does it need to be metal? I don’t know. Maybe rawhide’s fine and doesn’t need to be rendered in silver. I kind of like the idea that it’s skin.

That’s an interesting set of materials: rock, metal, skin. Why did you decide to make metal throwing stars?

I wanted to make throwing stars, but I wanted them to be lace. And then I was like, “How do I get the lace into metal?” I found a woman who does tatting, which is a way of making lace. This is an idea I had four or five years ago and then kind of rotated away from it and then came back to it. Part of why I came back to it was I figured out, technically, how to do it. I’ve made these blouses that were lace, from the Victorian period, into metal and these breastplates, lady armor, that have crystals embedded in them and various things—well, crystals and rocks I think of as some kind of power source.

I know about the brass knuckles. Have you done other weapon-type things? Is that an interest of yours?

Ever since college, I’ve been interested in both vulnerability and strength and the dichotomy between the two, and how you need both in your life. And this whole idea of protection: almost metaphorical protection and protection that’s actually physical. In grad school, some of this had to do with emotional vulnerability and how much I hated it, even though I knew that it was important. To fall in love, you have to be vulnerable. It started going into my work.

In college, somebody put a note on my car that said something super lewd and disgusting, and then I did this body of work called Women and Weapons. It was black-and-white, four-by-five photography. I had all my friends come—this is so feminist art school—wear masks in their bra and underwear and then hold a weapon. Some of them were made, and some of them were found. Just weird farm implements that looked like they could hurt you. I used to make steel sculptures out of farm implements, too. I was trying to do David Smith when I was between, like, twenty and twenty-five. They’re good photographs, but it just seems like a young, feminist, pissed-off little girl.

What got you into jewelry making?

The first piece of jewelry I made was the crystal brass knuckles, and then I started to think, “Well, I could have made, like, five thousand of them and sold them by now.” But I decided I wanted that to be the sculpture, and then I wanted to make some more wearable things. I liked the idea of the power of an object on your body. How a piece of art changes when it’s on you.

The brass knuckles seem to be at the intersection of several strands of your work, especially form: they’re wearable, but they’re also in a museum. Where do your jewelry and your sculpture intersect, and where do they depart from one another?

My friends who are really incredible goldsmiths and metalsmiths get offended if I say something is art when it has a little bit more of a conceptual basis. For me, jewelry is not conceptual. But when it’s more than just a thing that you wear that makes you feel powerful—it’s a really fine line. When I’m making the jewelry more, I’m just letting my hands do the thinking. I’m obviously making a lot of visual decisions formally. But it’s like knitting. It’s cathartic. I can watch TV and do it. I just love handling the materials and manipulating. I make them out of wax. With sculpture, making a piece of art, you stare at it a long time and try to decide if you made the right decisions and what decisions to make next. And you kind of torture yourself over playing with all the possibilities of it and how far you can push it. I don’t stare at a piece of jewelry for hours. Maybe I should.

Why do you think people responded so strongly to Crystal Brass Knuckles?

I was trying to fuse hip-hop and New Age in this ridiculous way. I think the idea of it being a healing tool and a tool of destruction in one—and it’s also visually interesting. When it’s photographed on the hand, it looks really intense. When it isn’t being worn, it’s not very exciting, I don’t think.

I feel like it relates to what you’ve been saying—maybe I’m just reading this into your work—about taking objects, types of objects, that are thought of as feminine or that come from a traditionally female sphere and bringing them into a zone of violence and protection. Like making throwing stars made out of lace. What or who are some of your influences?

I have some traditional ones, like Louise Bourgeois, and I really like Richard Tuttle. I used to love Bas Jan Ader because he’s such a sap, man. I was actually in a show with his film, I’m too sad to tell you [1970–71], where he just cries. It’s just a film of him crying! I don’t know if the word quirky is right, but I also think of Miranda July and some of her wacky ways. Not that many people make it okay to be sentimental in the contemporary art world. Even some early sculptors that are ladies are pretty tough as nails. And to try to be tough as nails and still sappy is tricky.

And that’s totally the line that you’re walking.

Right now I’m doing a project where I send these prints to 365 people, ladies, that say “so proud of you” on them, and then I have a little description of the project on a card with them. I’m writing letters of what each person means to me, which takes a lot of energy—and have really interesting responses, so they’re going to be people I’m close to, but also people like Miranda July and Björk.

Would you say the events of the last year, starting with the Women’s March and, this fall, the #metoo movement, are really present in your mind as you’re composing these letters and also as you’re working now?

It’s very hard not to let that affect you if you’re a woman. It might be unconscious in some ways, and then it comes out. It’s really seeping into what I’m making and thinking and concerned about. The name of my show in April is going to be Tooth and Nail, and that has to do with Salma Hayek in her article saying, “Why do women have to fight tooth and nail for dignity?” I feel like that theme is there, but it didn’t just start because of this year or anything. In grad school my whole thesis was all about two things: trying to embrace vulnerability, and the female voice. I was doing, and I still do, some tongues and some necks. In an essay called “The Gender of Sound,” Anne Carson talks about how women emote in such a way that they terrify people, and it might go into the whole history of hysteria, so I was making work about that; I even made some vocal chords saying, “I love you.” It’s hard to carve vocal chords out of stone, so it was still kind of this sappiness. I hadn’t quite gotten to making armor, but even now I’m trying to keep the female voice a part of it, because it’s always been a part of it. And I think that’s the biggest strength that women have right now.