This Blanton Museum of Art exhibition highlights how day jobs feed art practices by providing artists with materials, production methods, and ideas.

Day Jobs

February 19–July 23, 2023

Blanton Museum of Art, Austin

At the Blanton Museum of Art, the exhibition Day Jobs explores the impact of paid jobs on artist’s work to debunk the myth of the artist who sits in their studio, waiting for inspiration to strike. From hairstylist to lawyer, the exhibition cards highlight how artists’ life experiences feed their art practice by providing materials, production methods, and sparking ideas.

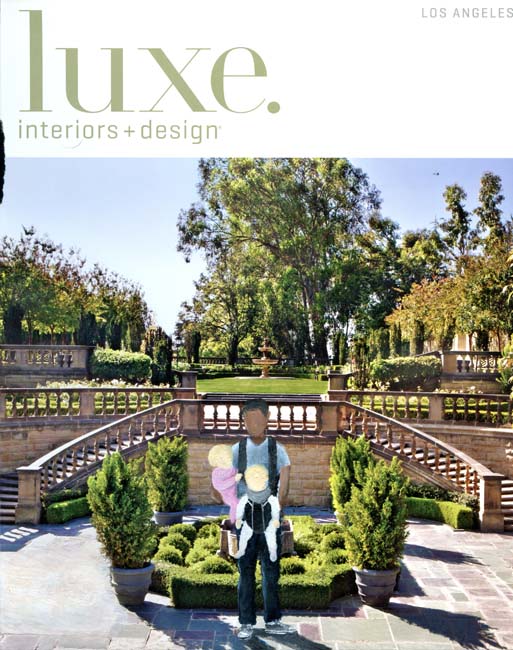

The show provides a straightforward entry point. Most everyone needs to have a day job (or more likely, jobs) to pay for food and shelter. Laser prints by Marsha Cottrell show a depth and delicacy made from the ubiquitous office printer. Work by Jay Lynn Gomez are an intervention. Gomez paints custodial staff and caretakers in high fashion magazine spreads to remind us of the invisible and outsourced work it takes to live in luxury.

Lenka Clayton’s 63 Objects Taken Out of My Son’s Mouth (2013) and Manuel A. Rodríguez-Delgado’s Piloto (Pilot) (2022), where the artist built a climate-controlled crate to hold a notebook of ideas, show how artists must contrive ways to make art while surviving in our society.

When I think of another stereotype, that of the tortured artist, I think of how the artist’s day job tortures them. I think about how people disparage artists and art because they can’t bear to face how their reality crushes their creativity and inspiration. I think about how something that doesn’t readily build financial wealth becomes something not worthy of value in our culture.

In the last sentence of the exhibition text, the word precarious hints at the complicated matter of the value of art in the U.S., but does not unpack the role museums play in it. Museum exhibitions pull work from their own collections or source artworks from other museum collections. Some works are borrowed from individuals who the museum hopes to make into donors or are already current donors. This lending involves insurance and yards of contracts, but as far as I know, no payments to the artists. The U.S. does not recognize resale royalty rights for visual artists, so when artwork makes a big headline for selling for millions at auction, the artist, no matter how big their name, gets nothing. All of this makes me want to know how many, if any, artists were paid as part of Day Jobs.

Reading the title cards in Day Jobs, viewers can follow the lending path of each work. When asked if there were any artist fees paid, Katie Bruton, the Blanton’s PR and media manager, explains:

Most of the artworks in Day Jobs were loans from museums, galleries, and private collections. Some were loaned from the artists themselves. Per the Blanton’s current practice, the museum does not compensate artists directly for loaned and previously created artworks shown in an exhibition. The Blanton does compensate for travel and in-person installation consultation. In this case, there were a couple of artists in Day Jobs that came to Austin to install their artworks; they received a travel and installation compensation. The artists that worked on Sol LeWitt’s wall drawing also received an hourly fee, in consultation with the artist’s estate.

Museums receive great amounts of funding, but when it comes to exhibiting work, it seems they provide payment primarily through prestige. This is understood as way of bolstering careers and pushing artists into bigger collections. Like the winding path any one of the works included in Day Jobs took to arrive to the museum or the many jobs each artist undertook in pursuit of their practice, making a living as an artist is complicated. Day Jobs is the start of what could be a long and deep conversation.

In Chuck Ramirez’s Whatacup (2002) a fast-food drink cup with the familiar orange lines of Texas chain Whataburger is blown up with text added in the middle where a logo would be printed. Ramirez’s marketing work at H-E-B, his HIV diagnosis, his untimely death in 2010, and our current pandemic make the work’s text haunting: “When I am empty, please dispose of me properly.”

It is my hope that this is not all we can ask as we toil away at our day jobs.