516 Arts, Albuquerque

November 17, 2018 – February 23, 2019

This is not an actual credit card, reads the plastic dangling from the handle of a clear acrylic briefcase on the first floor of 516 Arts. Inside the briefcase are stacked bundles, affixed with fake coins and addressed to the artist Jennifer Dalton. Your Name Here (2014) alludes to one of Hollywood’s favorite props—the briefcase full of cash—but replaces the sleek black with transparent plastic and the bundled hundreds with a year’s worth of credit card offers collected by the artist.

Currency: What do you value? puts Dalton and fourteen other artists in conversation about the problem of value in a world where the dollar seems to be the one unit of measurement that everyone can agree on—even if few can articulate what a dollar measures, or means. Manuel Montoya, who with Josie Lopez curated the exhibit for 516 Arts, says he teaches his students that money is the story you tell about an economy. For many of the artists featured here, though, what deserves our attention is not the story we tell but all the stories we obscure.

An adjacent display of identical blue dresses further emphasizes the tedium endured by textile workers, while also evoking the treadmill of consumerism.

The front-room installation, Debtfair New Mexico, resonates with anyone who has ever carried a secret briefcase full of debt. This project of Occupy Museums is animated by the vulnerability of ninety-seven New Mexican artists who made the bold choice to expose their debt: a collective sum owed of $7,338,581.

Even job-juggling, student-loan-burdened artists are indebted to the sweatshop workers of the world, as Christie Chow reminds us in Come Run in Me 2 (2017). Step onto Chow’s treadmill and its screens illuminate not miles walked and calories burned but images of hands feeding fabric through a sewing machine and the day’s schedule (complete eighteen dresses; toilet break; complete eighteen dresses). An adjacent display of identical blue dresses further emphasizes the tedium endured by textile workers, while also evoking the treadmill of consumerism.

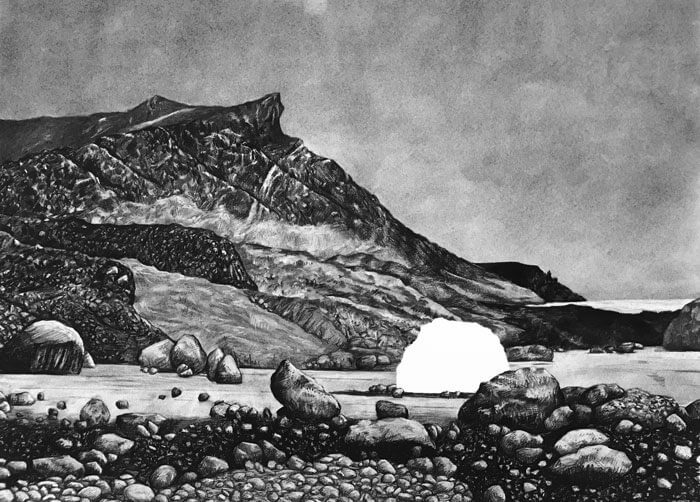

It’s possible to look at Nina Elder’s drawing, Ahnighito Meteorite, in transit to the American Museum of Natural History (2018), tucked upstairs, without at first seeing its subject. Lost in the close detail of chains, ropes, rudder, and sail, I briefly supposed the drawing to be a study in the machinery of money, a depiction of the materials and labor exterior to, but necessary for, the making of any product. Standing back, the meteorite becomes visible as a glowing white void at the center. The caption provides context for its journey: without permission, a white man removed this and two other meteorites from Greenland, where the Inuit had for centuries fashioned tools from the meteorites’ iron shards. In two smaller drawings, a similar white void represents each meteorite in its natural habitat, glimmering and mystical—reflecting the Inuit relationship to these objects while also suggesting that value is malleable, mutable.

The butterfly, a common symbol of transformation, takes on more ambivalence in the hands of Erika Harrsch. In Foreign Aid (2017) and Foreign Development Assistance (2017), butterflies are cut from the currency of wealthy nations whose neoliberal values are embedded in the conditions of their gifts and loans to poorer and developing nations—and in the paper currency itself. There’s Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s intellectually curious petit prince on a French franc note (no longer in circulation), the Queen of England on the pound, and the brutal, victorious General Grant on the fifty-dollar bill. These

butterflies, eerily ephemeral, hint at the very instability of currency.

In the late Tony Hoagland’s poem, “America,” the speaker describes a dream in which he stabbed his father and hundred-dollar bills gushed out. “Thank god,” his dream father says, “those Ben Franklins were / Clogging up my heart— / And so I perish happily, / Freed from that which kept me from my liberty.” The collective work in dialogue here, like the conclusion to Hoagland’s poem, reveals that it’s more complicated. We are enmeshed in a web of transactions that simultaneously reveal and construct our values—and it’s through art, not money, that we can converse about what we believe matters most. Together, these artists invite us not simply to question our faith in currency but to confront the disparity between market value and enduring worth.