Rachelle Pablo (Diné), 516 Arts’s newly-appointed curator who will unveil her first exhibition this weekend, aims to unpack nuance and adjust misrepresentations of contemporary Indigenous artists.

Rachelle Pablo (Diné, of Tachii’nii or the Red Running into the Water Clan and born for the To’aheedliinii or Water Flows Together Clan, of the Tsenjikini or the Honey Combed Rock People or Cliff Dwellers People Clan, of the Tl’aashchi’I or the Red Bottom People Clan) has always been surrounded by art. Her grandmother, who raised her until the age of four, was a weaver and introduced Pablo to fiber arts, textiles, and abstract geometric design. Rather than a “fine art practice,” the highly esteemed act of weaving was enculturated in Pablo’s family and her broader community as a philosophy and an intrinsic value of a way of life—making textiles on a loom is a sacred tradition that invokes deities, creation myths, and more.

Despite being raised in this creative paradigm, the Gallup, New Mexico-born Pablo was sent to a Native American boarding school and assimilated into Western culture, which sequesters art into a much more restricted category. Because of the strict limitations on what counts as art and who can call themselves artists, Pablo spent many years thinking she was or could not be a part of the fine art world. It wasn’t until later that Pablo pursued a career in the art world as an artist and curator by enrolling in fine arts coursework at Albuquerque’s Central New Mexico Community College.

After Pablo completed her MFA in art history from the University of Delaware and earned a BFA at the Institute of American Indian Arts, she understood that her grandmother’s weaving practice was contextualized differently in the institutional art world. This distinction between the way two cultures define art and artistic practice is what informs her work as a curator today.

Pablo is the newly-appointed curator at Albuquerque’s 516 Arts, where she will develop exhibitions and programming that approach themes of migration, borders, environmentalism, and queer identity from a different angle. Along with including work by Indigenous artists whose work has been erased from the canon, Pablo hopes to incorporate ancestral knowledge in the public programs she develops alongside her exhibitions. Among her curatorial goals is a desire to authentically engage and build trust with Indigenous communities by honoring Native artists and adjusting any misrepresentations projected onto them by a Western lens.

Her scholarly research focused primarily on the work of Otellie Pasivaya Loloma, a Hopi potter and dancer whose work is often left out of the traditional art history surveys of the 20th century—as are so many legacies of Indigenous artists. Pablo wants to ensure this erasure does not continue happening by including and uplifting the work of contemporary Native American artists in her exhibitions.

Pablo’s curatorial angle is not only about focusing on Indigenous artists, however. She also wants to emphasize and outline the nuanced communities and cultural exchange of New Mexico and the Southwest. She points out that intersectionality is an important part of the conversation, noting the complexities of Chicano and Genízaro culture that are present in this region.

“I really appreciate that I’m doing curation because it’s pushing me into the reality that we’re not just segmented people, we’re all together,” says Pablo, reflecting on the fact that New Mexico communities are not culturally insulated, but always interacting, associating, and exchanging with one another.

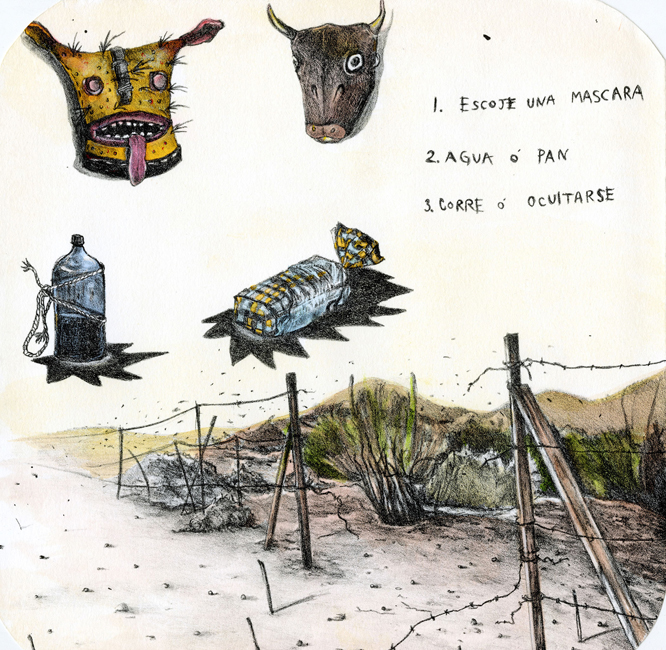

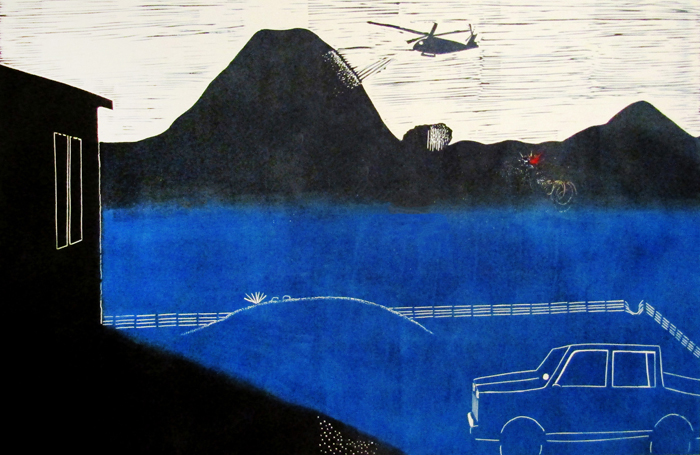

These values of intersectionality and cultural remediation play a big part in her first exhibition at 516 Arts. When the Dogs Stop Barking, opening October 1, 2022 and on display through December 31, 2022, encompasses printmaking, drawing, painting, and sculpture, and explores the humanitarian crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border through the work of Haley Greenfeather English (Red Lake/Turtle Mountain-Ojibwe/Irish), Juana Estrada Hernández, Makaye Lewis (Tohono O’odham), Yvette Serrano, and Joshua W. Wells.

Oftentimes, the best way to thoroughly unpack a collective experience is by looking at it through individual modes of expression to get a holistic perspective. Ideas and messages delivered in the show include the reality of the prison industrial complex, the dangerous journey awaiting people who seek opportunity in the United States, and the process of dehumanization that occurs at the border. A majority of the presented work was made by artists who are living or have lived along the border, and it is their lived experience that’s given a platform.

The exhibition title takes its inspiration from Roxy Didn’t Even Bark, a print in the show by Lewis that portrays a scene of a dog refraining from barking at people crossing the border. Dogs are often prone to barking at threats, but in Lewis’s piece, Roxy’s enduring silence and friendly disposition toward the border-crossing travelers reminds us to question who we consider dangerous.

“It’s about the humanity of the other-than-human dog Roxy who would no longer bark at the migrants,” says Pablo, “and the inhumanity of the Department of Homeland Security.” Pablo cites U.S. immigration policies that are meant to act as deterrents for illegal immigration, but instead force people into environments of human trafficking, exploitation, and carceral violence as the root of the brutality inflicted by Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers.

Beyond the exhibitions currently slated for the next year at 516 Arts, Pablo has a critical eye toward environmental justice. She has an increasingly growing interest in the fraught relationship between Los Alamos National Laboratory and the surrounding Pueblo communities. She notes that LANL employees have tapped into the artisan markets of the Santa Clara and San Ildefonso pueblos, but though there is economic support and exchange, the lasting negative effects of nuclear waste and uranium extraction diminishes those peoples qualities of life.

For certain professional development workshops, she’s lined up organizational partnerships with Albuquerque’s Indian Pueblo Cultural Center. She’s most excited about including and working with the “cultural knowledge carriers” who will share their wisdom with the public through free, hands-on classes such as an upcoming mycelium workshop with Beata Tsosie-Peña (Santa Clara Pueblo). Ultimately, the rich combination of exhibitions and public programs organized by Pablo will serve the community by giving space and visibility to the cultures that give profound vibrancy to this place.

Pablo is also developing more public programs that create career accessibility for Indigenous artists. The art world is an intimidating force and she’s observed that so many Indigenous creatives think that they may not have what it takes to make it as working artists. But Pablo believes that all it entails is someone acknowledging talent and potential to bridge the gap.

“I’m hoping to create accessibility to the many people who believe that they aren’t capable of a career in the arts, like I did,” says Pablo. “I didn’t fully immerse myself in the arts until later in life because I didn’t feel I was of the caliber of a museum artist, but I’ve had a lot of support along the way.”