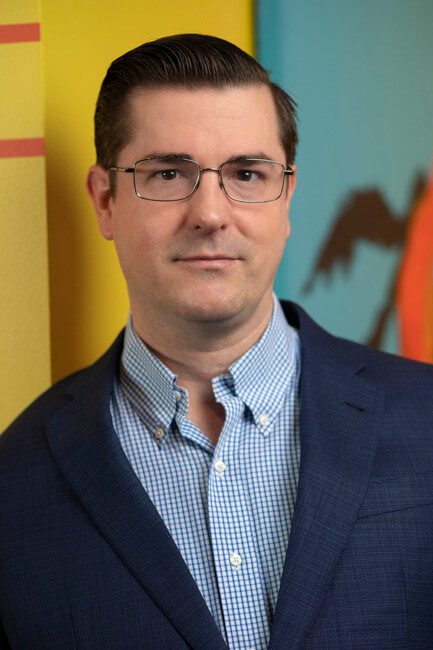

Curator John Lukavic leads the Denver Art Museum’s well-regarded Native arts collection—and its mission of historically and culturally sensitive exhibitions.

DENVER, CO—In the ongoing and crucial conversation on how to present Indigenous art without sidelining Indigenous people, John Lukavic is part of a vanguard of curators advocating new approaches.

Lukavic, the Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Native Arts for the Denver Art Museum, has much to be proud of from the last several years. In 2015, his department debuted Super Indian: Fritz Scholder, 1967–1980, with more than forty rarely seen works. In 2018, DAM presented Jeffrey Gibson: Like a Hammer, the first major museum exhibition of the Native American artist’s multidisciplinary works. And the summer of 2021 brought DAM national attention for Each / Other, featuring renowned Native artists Marie Watt and Cannupa Hanska Luger and their first-time collaboration, a giant she-wolf covered in donated bandanas.

The acclaim doesn’t stop there, though. Lukavic and his team have spent several years overseeing the reorganization of DAM’s vast Native Arts collection, and in the process, have reimagined how the third floor in the Martin Building could look and function. Thanks to their vision, traditional and contemporary art objects, sculptures, and paintings now emphasize context and inclusiveness in their examination of Native history, culture, and diversity. The public response has been effusively positive since the Martin Building, formerly the North Tower, reopened in October 2021.

So it’s a fitting insight into Lukavic’s way of doing things that the first stop in our Martin Building walk-through is the glass text wall in the lobby, which points out how the museum sits on the homeland of the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Ute people, even as the view out of the window takes in the Colorado State Capitol. Lukavic, who’s sensitive to the fact that he’s a non-Native curator of Indigenous art, motions to the text, which notes not only the displacement of tribes but also the theft and historical misrepresentation of their arts.

How can a curator address such misdeeds and bring the presentation of Indigenous arts into the 21st century? About midway into the walk-through, Lukavic makes a comment that seems to encapsulate his philosophy.

“There’s a trend in museums of incorporating Indigenous arts into American art collections, which is a fine, valid approach. Here, we take a ‘yes, and’ approach,” says Lukavic, who adds that when he was young, he developed close relationships with several Indigenous families “who treated me as one of their own,” he says. “I later moved to Oklahoma to study at the University of Oklahoma and had many more opportunities to expand my network and learn directly from elders. That sparked a lifelong passion for Indigenous arts.”

He explains that while the Indigenous Arts of North America collection commands more than 20,000 square feet, there’s much more Indigenous art to be found in the museum’s textile collections, its Western American Art floor, and its contemporary galleries. “It’s a ‘yes, and’ approach because we are incorporating Indigenous art into these global conversations and committing to presenting really good stories that quite honestly would get lost if we put them in the context of colonial stories,” says Lukavic.

Context and inclusiveness matter, and Lukavic shares several examples of art objects that are grouped together to offer a more comprehensive picture of Indigenous history and culture. For instance, in one corner, visitors can find Kent Monkman’s (Fisher River Band Cree) History is Painted by the Victors (2013), an imagining of Custer’s soldiers lolling at a mountain lake, along with a pictograph painting on muslin (circa 1890) by White Swan, one of Custer’s scouts, recording the Battle of the Greasy Grass, also known as the Battle of Little Bighorn. Together, the works are historical and contemporary takes on a pivotal moment in Indigenous history, and they are meant to be in dialogue.

DAM’s installations of its permanent collection over the last decade (pre-Martin Building reopening) proved that historical works and contemporary pieces needn’t be shown chronologically, but can coexist side-by-side, “to show continuity as well as innovations over time,” Lukavic says. Furthermore, “contemporary works can activate historical works” and give the latter new meaning, he says. One example that sits amid contemporary works is a late-19th century beaded Lakota vest bearing inverted American flags. Its “distress-signal” messaging is still relevant today given the long-lasting impacts of colonialism, Lukavic says.

This month marks Lukavic’s tenth year with DAM, where positions in the Native arts department led to his promotion to curator in 2017. His PhD is in cultural anthropology from the University of Oklahoma; his doctoral fieldwork focused on Southern Cheyenne moccasin makers and religious leaders in Oklahoma. In addition to his scholarly research and writing on Native American art, Lukavic was selected for the Getty Leadership Institute in California in 2018, which recognizes emerging talent in the museum field.

Lukavic is particularly proud of the depth of DAM’s Native arts collection and how the museum has kept up with collecting contemporary works across several decades, making the collection one of the best in the country.

Represented artists include Fritz Scholder (Luiseno), Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes), Rick Bartow (Mad River Wiyot), Jody Folwell (Santa Clara), and Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit and Unangax). Many of the contemporary works tackle sensitive subject matter, such as the history of violence against Indigenous peoples, relocation to reservations, and forced removal to boarding schools. A new “Reflection Space” offers a quiet place to process the artists’ messages. Elsewhere on the floor, sections spotlight arts and crafts across the centuries according to region, and a vibrantly colored circular room called “Home / Land” gives voice to the peoples who settled in what is now known as Colorado. Videos throughout the galleries feature interviews with Native artists and community members.

Just below this collection, as part of the second-floor offerings, is the Northwest Coast and Alaska Native Art Gallery, also curated by Lukavic’s team. It’s popular for its monolithic memorial poles and artifacts across several decades, much of which has recently been given new labeling to better explain the objects’ historical and cultural significance.

Lukavic—standing near the Indigenous Arts floor’s monumental Roxanne Swentzell (Santa Clara) sculpture, Mud Woman Rolls On—comments that many of the works on view feel personal to him, given the relationships he’s developed with artists over the years through his roles in acquisition and curation. “But there’s also this sense of responsibility in showing these works,” he says, “because the stories behind them, the emotions that they elicit, are just so powerful.” Lukavic’s passion for doing the right thing aligns perfectly with the words on that glass wall in the lobby: “While we cannot change the past, we can change how we move forward.”