April 21 – July 9, 2017

Center for Contemporary Arts, Santa Fe

In the early 1970s I worked on a radio show at KPFA in Berkeley called Unlearning to Not Speak. It was a historical moment when educated, middle-class, Western women articulated how we had been silenced, marginalized, excluded by the culture we lived in. In some ways the world has changed (imagine world politics today without Theresa May, Marine LePen, Angela Merkel, or Hillary Clinton). This exhibition—ranging from works produced on smart phones to sculptures containing cement or furniture spindles—reopens feminist critical concepts, revealing how relevant the discussion still is and, in some ways, how little has changed—especially for those whose gender identity or sexuality is not normative.

Proposing that women’s experience needs to be seen, heard, and cherished—and that to unabashedly express emotion is a necessary political gesture—CCA solicited works from female-identified artists of varied ages, ethnicities, and geographical areas in an open call for the exhibition Cryin’ Out Loud (April 21-July 9, 2017). Juried and curated by critic and artist Micol Hebron, the exhibition includes over fifty artists.

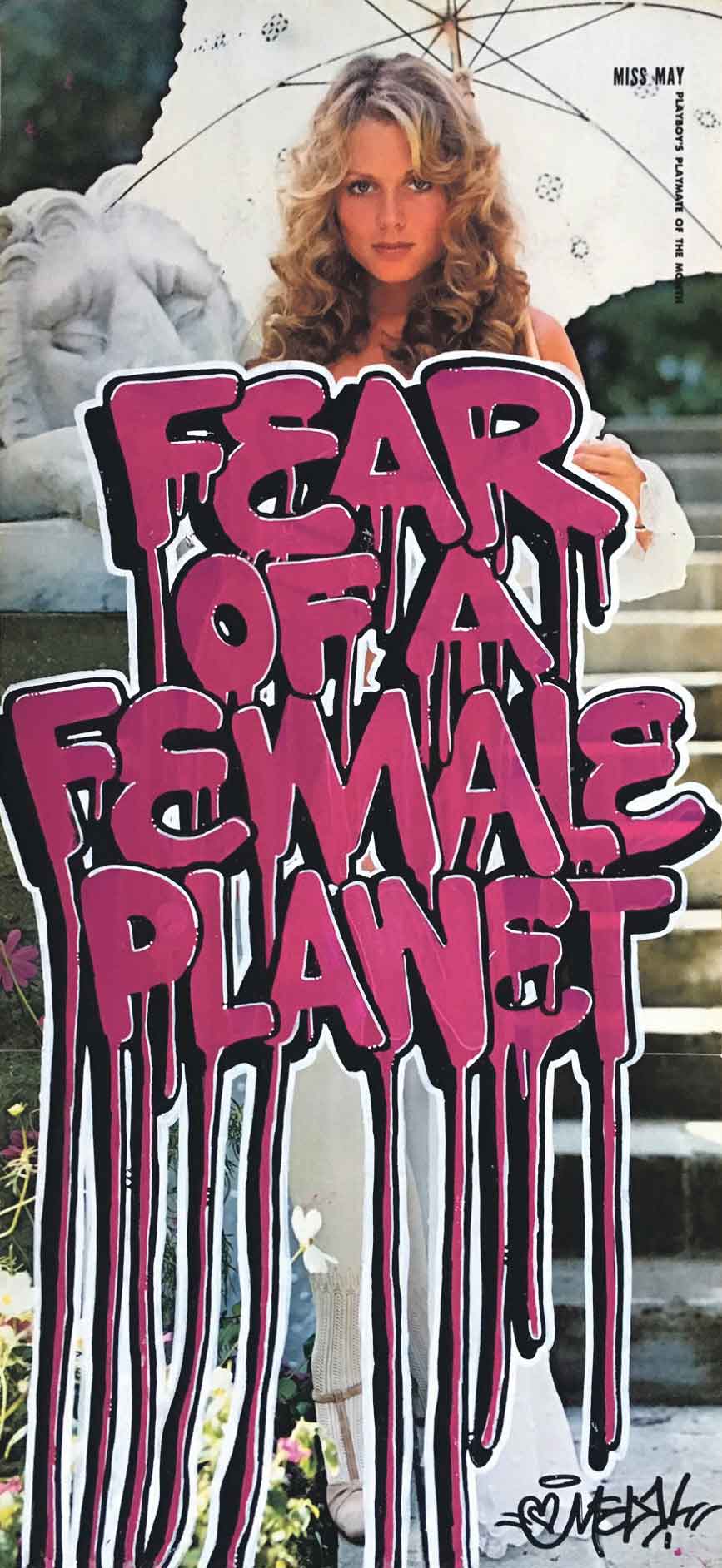

Themes such as “The Male Gaze” organize the displays: “Hidden/Revealed” shows how women have historically been excluded from public discourse yet put on display as bodies to be consumed. Pieces in “Mothers & Foremothers” examine motherhood and childbirth or mock ways in which women’s “labor” has been effaced by society. Hidden Mother by Megan Jacobs sends up Victorian baby photos in which the mother is covered up, substituting cheery, modern flowered sheets. Two Mother Suit pieces by Kasey Jones wittily highlight the difficulties of combining nursing an infant and holding down a job.

Countless monuments honor male leaders and warriors, but how many celebrate the enormous commitment of birthing and nurturing a human being?

Susan Begy’s Precious Possitions (intentional misspelling to also reference “possessions”) called to me from across the room. A large cube covered with shards of glass acts as pedestal for two carved alabaster forms, split like a geode; from them, ambiguous shapes—a baby, a bird, a gun—emerge. Pairing broken glass that one normally throws away with a stone usually associated with flawless classical statues offers a visceral juxtaposition suggesting the asymmetry of value that women have struggled with over the centuries. Countless monuments honor male leaders and warriors, but how many celebrate the enormous commitment of birthing and nurturing a human being?

Cecilia McKinnon’s Home Remedies complicates an armchair with intricate embroidery in such a way that it cannot be sat upon, a sardonic disruption of a time-worn female labor. In Screen Repair, McKinnon “mends” an ordinary window screen with brightly colored threads that transform the utilitarian object and enact a sly insertion of feminine activity, restoring the screen to its original functionality while also evoking the electronic screens that dominate our lives. Stephanie Lerma’s Momma is two aluminum breasts cast from a knitted one. Mother Tongue (print and object), a bronze cast of artist Courtney Kessel’s own tongue, also features in a staged photograph and alludes to the familial genealogy of gender roles and gendered language.

The show includes documents and fragments of performances and many strong graphic pieces, drawings, collages, and paintings: Alison Kuo’s Meter Maid with a blacked out face and Rachel Rivera’s beautifully drawn Mourning Hat I stand out; a large book made up of protest signs (a reviving folk art these days in the US) is presented by Melissa Potter and Maggie Puckett.

In the “Trauma” section, works express grief for injustice and environmental damage; assert ethnicity, gender, and sexual identity; and celebrate survival of trauma. Evincing contemporary influences—Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, or Shirin Neshat—they interrogate and challenge norms of body image and the roles of masking or camouflage. Quintan Ana Wickslow’s Fieldwork is a text and image work that contemplates the femicide region of the US-Mexico border, where the bodies of murdered women are dumped or buried. The “Portraits” section mounts numerous self-portraits, letting both their similarities and uniqueness unfold.

In Nikesha Breeze’s painting, The Space Between, the small, upright figure of an African American child confronts nine Ku Klux Klan figures looming like sinister judges. The hoods are echoed in adjacent works, such as Bette Davis and Joan Crawford (Who’s Afraid of Baby Jane) by Maureen Hawthorne, which offers multiple curtained images of the duo as iconic grotesques of their earlier glamorous personas.

Sallie Scheufler’s Encouraging Banners for the Female Orgasm uses the bright foil letters that usually say “Happy Birthday” to instead spell out explicitly female sexual requests. The tremendous vitality of all the works is reinforced by the installation, allowing them to enact a multi-vocal conversation.

“Speaking Truths” features video works by ten artists, including two works by veteran feminist artist Cheri Gaulke and NO: You Do Not Have My Consent by Eliza Fernand, an animated montage of quilted iterations of “NO.” Jessica Fairfax Hirst’s A Letter to my Rapist enacts the power of speaking out, talking back, and having the last word. I cannot end without mentioning Kate Cassat Tatsumi’s Tit Tub, an inflatable kiddy pool full of round pillows with bright pink nipples. Viewers (shoeless) can wade in. Do so.