Curated by Erin Joyce, the small-scale exhibition at ASU Art Museum posits big questions about art and craft, resistance and identity.

Crafting Resistance

August 19, 2023 – July 14, 2024

Arizona State University Art Museum, Tempe, AZ

Crafting Resistance, occupying the third floor of ASU Art Museum, is a small-scale exhibition with huge impact. Curated by Erin Joyce, the show includes large and miniature installations, cotton “paintings,” a boxing video, and glass works by turns refined, piled, and—when combined with aluminum, rebar, and other material—resembling familiar objects made unrecognizable by an atomic heat blast.

Resisting what, each of the works asks? The answers include: The binary of craft and art. Colonialism. Geo-politics. Environmental degradation. And, last but not least, expectations.

True: the artists use media often related to craft in their work, not only glass and textiles, but also felt, wood, and found objects. But they deploy these materials to charged effect. The “blanket” installations by Eric-Paul Riege (Diné) defy suppositions of craft and its often-embodied definitions of functionality. Using plastic sheeting, packing materials, muslin, polyester, and yarn, Riege creates hanging works of transparency and insubstantiality that confound notions of a traditional blanket’s meaning and purpose. And upend expectations of what the crafting of a “Navajo” blanket entails.

Jayson Musson’s XXII-IV – Periscope and XXIII-III – Diurnal (2023) interrogate cultural memory by weaving mercerized cotton into “paintings” recalling the 1990s Coogi sweaters immortalized by actor Bill Cosby, known as “America’s Dad” for his portrayal of fictional character Cliff Huxtable on “The Cosby Show.” These works unravel any warm and fuzzy associations with Cosby since his convictions for sexual assault. Moreover, the vibrantly colored sweaters weren’t an American invention but an Australian fashion brand also made popular by rappers like Notorious B.I.G. and Snoop Dogg. In these works, then, fine art and craft, visual memory and its associations, even Black identity come into play.

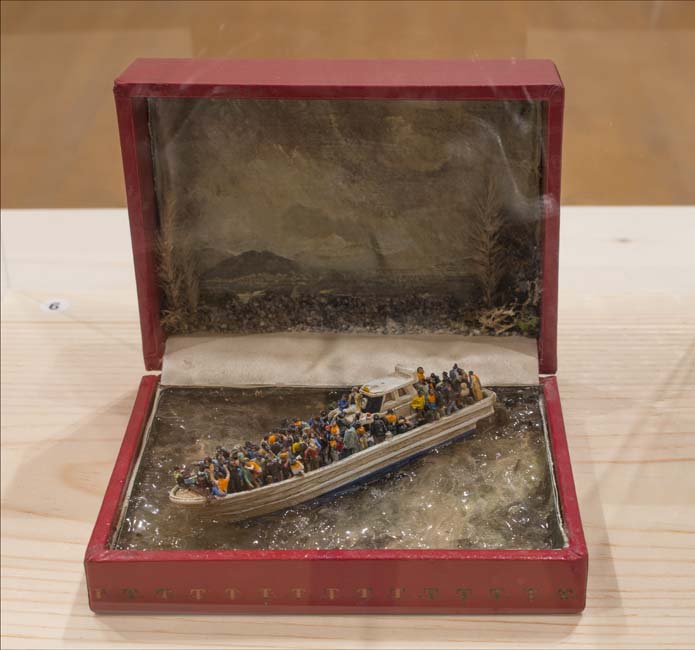

At first glance, the tiny dioramas in Curtis Talwst Santiago’s Infinity Series (2012-present), emanate a vintage charm. Crafted of minuscule objects in old jewelry boxes, the artworks are not, however, precious. Toy boats sit heavily in turbulent seas weighted down by desperate figures. A strange creature has raced across a vacant lot as smoke billows from a house peeling away from itself. There’s a sense of the mythical in these artifacts, encased in vitrine-like plexiglass boxes, while they silently speak to trauma experienced by people in the world today.

Meanwhile, Andrew Erdos’s gorgeous Ghost Vases (2020), with their side splits; his glowing heap of broken antique glass colored with depleted uranium, Before the Great Awakening (Uranium Mountain) (2017), and other works singly and in collaboration with Yasue Maetake agitate in the liminal space between life and decay, beauty and ugliness, shape-making and its destruction. Merryn Omotayo Alaka and Sam Fresquez re-envision Western stereotypes about identity in their beautifully crafted puzzle-like pieces and sumptuous chandelier-like work. And in her video, Sama Alshaibi uses her body as art, literally punching through notions of Indigenous identity with playful aplomb, while merging the visual, aural, and technological in a well-crafted piece that slays.

Resistance, to recast a famous quote from Star Trek, is not only not futile, but alive, feisty, and firing the spirits of artists to create captivating work.

blanket. they get cold 2, 2021, mixed fibers. Photo: Craig Smith. Courtesy the artist, STARS, Los Angeles, and ASU Art Museum.