Container, an offshoot of Turner Carroll Gallery in Santa Fe, offers a model that prizes artists, curators, and artwork—some saved from the ultimate demise—over profit.

SANTA FE—When Swoon could no longer justify spending $2,500 a month to store—for an indeterminable amount of time—her large-scale sculptural installations Seven Contemplations, which had just been shown at the Albright Knox Museum in New York, Tonya Turner Carroll, who represents the artist, hatched a plan.

“The show happened during the pandemic, so I was only able to see it online,” Turner Carroll says, standing inside Container in Santa Fe’s Baca Railyard District. “I loved it so much, having it here grew out of my own desire to see it in person. We literally bought this building to serve that purpose.”

Turner Carroll, who opened Turner Carroll Gallery in Santa Fe with her husband in 1991, couldn’t bear the thought of an incredible body of work being destroyed, which Swoon was ready to do.

Unfortunately, this was a familiar story.

Judy Chicago, another artist Turner Carroll represents, destroyed much of her early work because she couldn’t afford to store it, and Turner Carroll had seen too many museum exhibitions disappear too soon because they had nowhere to go—primarily because the cost to ship or store the work was too steep and curatorial budgets too low.

“I told Callie [Caledonia Curry, AKA Swoon], I will personally take my savings account, and I will pay to ship [Seven Contemplations] here, and I’ll fly you and your team out to reassemble it,” Turner Carroll recalls. “I will get the wallpaper printed—which she designed and which has to be custom-printed every time to fit the space—because I believe this show has a life and needs to travel to other museums.”

Turner Carroll helped facilitate the shipment of part of the show to Japan and exhibited the work there before moving it to Container, the 5,000-square-foot space Turner Carroll opened with her husband and business partner Michael Carroll in October 2022 to give shows like Seven Contemplations a longer run and introduce them to new audiences. Swoon’s exhibition was the first in the space.

“We never wanted to expand, but when it became about the death of artwork we loved, then it became a ‘saving it’ kind of thing,” says Turner Carroll.

Container, quite literally made of shipping containers, is drenched in natural light and boasts ceilings nearly twenty feet tall, allowing for bigger shows and events than those at Turner Carroll Gallery, the space the couple continues to operate on Canyon Road.

“It was clear to us that we needed a different kind of space to do what the artists need to have happen for their careers,” says Michael Carroll. “Part of what is driving that is just size. We couldn’t show the touring museum shows that our artists were having. Container is an extension of our more ambitious goals for artists.”

Though Container is not a museum, Carroll says it’s acting like one. Private collectors are blocked, to a degree, he says, from sharing their work with museums, unless the museums are run by universities, because it’s seen as a conflict of interest. In other words, the exhibition “is perceived as enriching one guy’s whole collection.”

Container is not limited in what it shows—or sells. If someone wants to buy an entire installation, they can, with one caveat. Turner Carroll tells about a man who wanted to buy one of Swoon’s temples currently on display, to which she said, “Yes, you can buy that and get credit for it, as long as you are willing to allow it to travel any time it’s asked. If you’re not, then you can’t buy it.”

Their mission to be art-centric and artist-centric means profit comes second.

“This show [Seven Contemplations] will probably be a big financial loss,” Turner Carroll admits, “but it will be everything we wanted it to be.”

Essentially a private art space, where museum-caliber artwork is collected, sold, and exhibited, Container is a cross between an art center, museum, and gallery. Carroll says he’s not aware of a similar model, and he and Turner Carroll are still looking for the words to define what exactly Container is.

“It’s an institutional space because we only bring institutional shows here,” Turner Carroll says. “We take them out of public institutions that are burdened by bureaucracy into a private setting where we have no one to answer to.”

This new model champions curators as much as artists, and onsite residencies are available for both.

Container will also offer curatorial grants. Curator travel budgets are “unbelievably small,” as Turner Carroll puts it, citing an example of about $200 a year. With this in mind, she and Carroll have created grants for each of their shows at Container. They identify museums that have the physical space to exhibit the work, send them a catalogue, and offer to pay for a curator to visit Container to see the work in person.

During Swoon’s show, Turner Carroll received a call from the director of the Taubman Museum of Art in Roanoke, Virginia, who agreed to exhibit not only Seven Contemplations but also the additional pieces by Swoon that currently hang throughout Container—in effect growing the show from its original form. Finding new locations for shows is one way in which Carroll and Turner Carroll can expand the lifespan of artwork they believe in.

As they continue to run Turner Carroll Gallery, they’ll sometimes use both spaces to realize one idea. For instance, Beverly McIver: Retrospective.

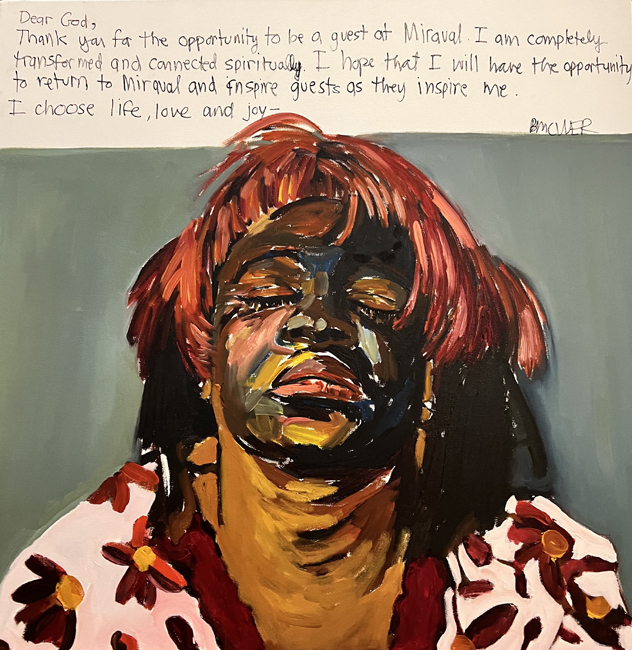

Turner Carroll Gallery is exhibiting a selection of McIver’s deeply personal paintings—often self-portraiture in black-face clown makeup—that explore her vulnerabilities growing up as a Black woman and her relationship with a white man. Some pieces include journal entries that have been torn out and hand-sewn onto canvas. Her Dear God series, which McIver began during Barack Obama’s presidency as a way to express her hopes and fears, is on display at Container. Events coinciding with the show, which runs through March 10, 2023, took place at both locations.

“Container really can’t exist without our other space,” Carroll says. “They have to work together.”

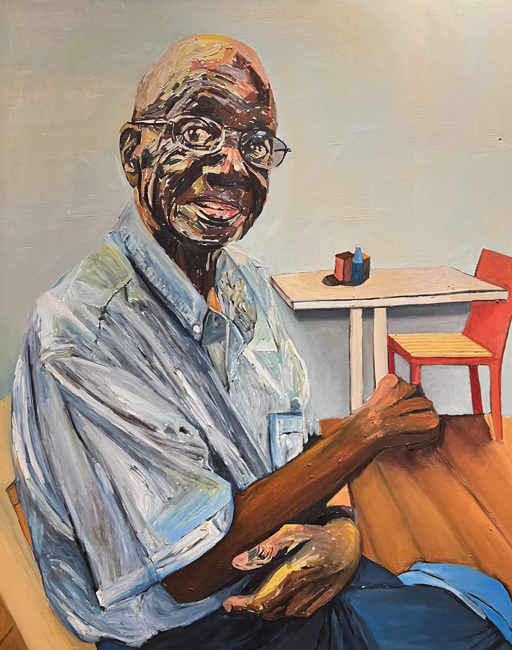

Another component of realizing Container came by way of Hung Liu, the late Chinese American artist Turner Carroll represents. In 2021, Liu died from pancreatic cancer just weeks before the opening of her retrospective at the National Portrait Gallery. She was the first Asian American woman to ever have a solo show there.

Turner Carroll, who considers Liu to be the top Chinese American female artist in the world, worked with Liu’s San Francisco dealer to inventory all of her pieces and halt sales in order to keep the work from being speculatively sold to galleries.

“We worked really hard to get places like the Whitney, MoMA, the Met, and the National Portrait Gallery to get major pieces of hers while all the best work was still available,” Turner Carroll says. “At the same time, we did make money from finding the collectors to buy work, we still got our part, so we decided to invest everything we made into something that would honor her. We took that exact amount of money, and we bought this building.

“We decided we would show work that we believed in so strongly—without limitations of how much it cost to bring the work here or how much effort or how long it took us—essentially with no commercial interest… and, like [Liu], we have a very strong interest in representing people who are war refugees, people of color, women, people who are marginalized in any way.”

A selection of Liu’s work, echoing her retrospective at the National Portrait Gallery, will be shown at Container beginning July 28, 2023. Pieces created by Robert Rauschenberg in China in the 1980s, when Liu was living there, will also be included. Turner Carroll tells how Liu encountered Rauschenberg at the Venice Biennale in 1989 and only had her Chinese passport on hand but wanted his autograph—so he signed her passport and told her, “This is your visa to the art world.”

“In some cases, artists of color have never had the opportunity to show [their work], so they are way behind the ‘old white guys,’” Turner Carroll says. “We are curating some shows of women of color alongside the old white guys so that they then are perceived as equal, kind of a shortcut to elevating their stature.”

This year, Container will also show geometric abstraction pieces by New Mexico-based artist Mokha Laget, life-size sculptures depicting the bodies of slaves in Cash Crop by Stephen Hayes, and a “printmaking performance” by Martin Begaye.

“I love the idea of a building made of containers that have been all over the world as a vessel to hold all of these different things together,” Carroll says.