IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, Santa Fe

July 7, 2017 – January 21, 2018

A single visit to the Institute of American Indian Arts’ Museum of Contemporary Native Arts is enough to prompt wonder at why those visits are not more frequent. It’s a rewarding museum, offering a fresh and significant perspective on what contemporary Native art is and might be. Parking issues aside, the IAIA MoCNA is a near-perfect venue for viewing contemporary art. That the art happens to be made by Native people adds to the pleasure of discovering work by artists who should be well-known to the art world.

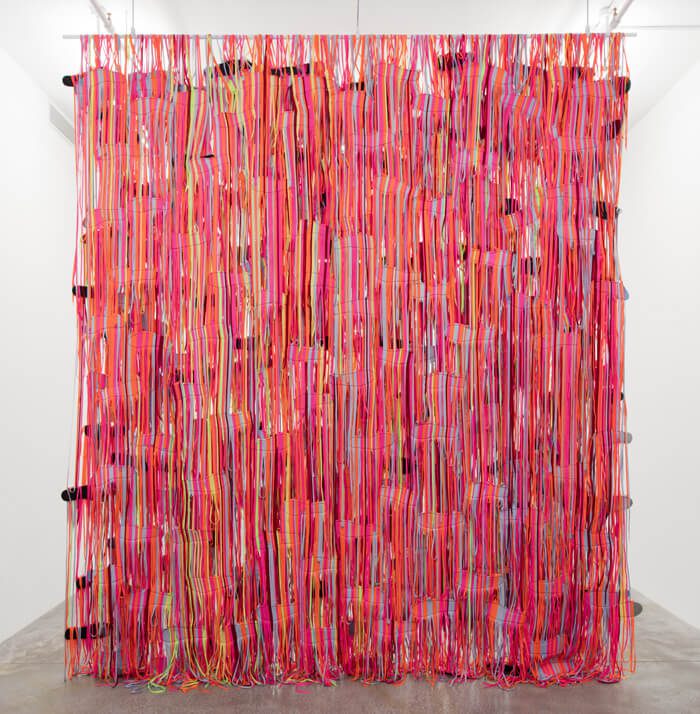

The entryway into Connective Tissue, which is held in the main gallery, doesn’t give much away, aside from what appears to be the visual chestnut of a quilt—rather an expected platitude. Passing inside the center wall, however, is when the fun begins. The main gallery is anchored by Brian Jungen’s striking 27th Street. A hanging curtain of bright pink and orange shoelaces form the vertical warp and Nike insoles stuck here and there form the weft. Jungen’s piece deconstructs objects that take on cultural significance—ridiculously expensive, must-have Air Jordans, for example. It’s also retinally pleasing, and makes for an intelligent centerpiece, replete with the subtext that it’s not only Native people who make objects that are rich in cultural meaning (as anthropologists in the not-too-distant past might have had us believe). The entire exhibition is smart and good-looking, a chic combo that impresses with how curator Manuela Well Off Man has raised the bar—already high—for future MoCNA shows.

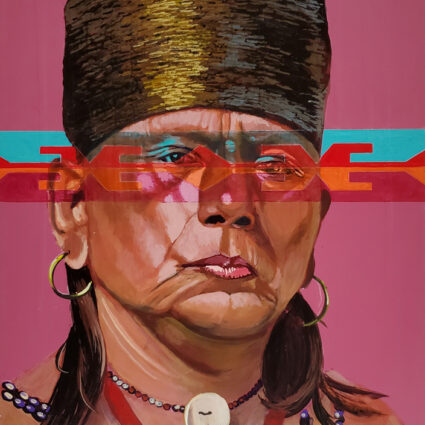

On the house’s left of the central gallery is a stunning installation made by local artist Cannupa Hanska Luger. His Savage Noble is a play on the term “noble savage,” which came into usage in the late nineteenth century, when the Native population appeared to be on the verge of extinction due to genocide, disease, and assimilation. No longer seen as a threat to Manifest Destiny, the Indigenous man was now a figure of nostalgic yearning for the frontiers of yore, the wild and fierce beauty that had been before the transcontinental railroad began its inexorable “winning” of the West. Part man, part beast and fully formed out of a cast of horrors, Hanska Luger’s Noble is a snarling hybrid to behold. Red yarns and other blood-colored fabric bits suggest an apocalyptic slaughter that exists in the past, present, and future. There is a visceral revulsion that feels reminiscent of the old, gory tales about white men shooting herds of bison from the luxury of their rail cars, leaving behind the gore of flyblown carcasses rotting across America’s once-fruited plains. The work is stark, beautiful, and tragic as a fatal car wreck.

Meghann O’Brien’s Sky Blanket (Cloud Blanket), a black-and-white weaving in the style and tradition of Chilkat blankets, depicts three faces: ancestors, their living descendants, and those yet to be born, and aptly illustrates the curator’s point when she posits,

Contemporary artists who work in fiber art are very much aware of the rich traditions and history of this art form and medium. Consequently, one of the most common conceptual tools in fiber art involves the revival, innovation, or distortion of those traditions. …Fiber also engages because of its attachment to gender stereotypes and cultural heritage, as well as the material’s associations with domesticity and homeliness.

Marlowe Katoney’s weaving Angry Birds–Tree of Life functions similarly, using video-game humor to belie the seriousness of water issues on the Diné reservation. Another Navajo artist, Melissa Cody, presents her Dopamine Regression, its eye-dazzling patterns and colors a response to the paroxysms of her father’s Parkinson’s disease. Ashley Browning, of nearby Pojoaque and Santa Clara Pueblos, contributed her deceptively simple collage, Paper Doll, to remind the viewer that the people seen dancing on Pueblo feast days are not mere re-enactors of the past; they are the living and breathing present and future.

In the next gallery, Polar Bear Curl by Sonya Kelliher-Combs is a piece that unabashedly uses the vocabulary of Eva Hesse’s postminimalist serial repetition to convey a sense of intimacy. Each skin-like layer of acrylic polymer is permeated by reindeer and polar bear fur and shaped into a curled sconce, about twenty of which hang in a long, ritualistic row on the wall. The curls mark time as endlessly as the surf and the seasons, and convey a hominess that is comforting and strange.