Phoenix-based artist Claire A. Warden experiments with camera-less processes to push against the boundaries of photography and identity.

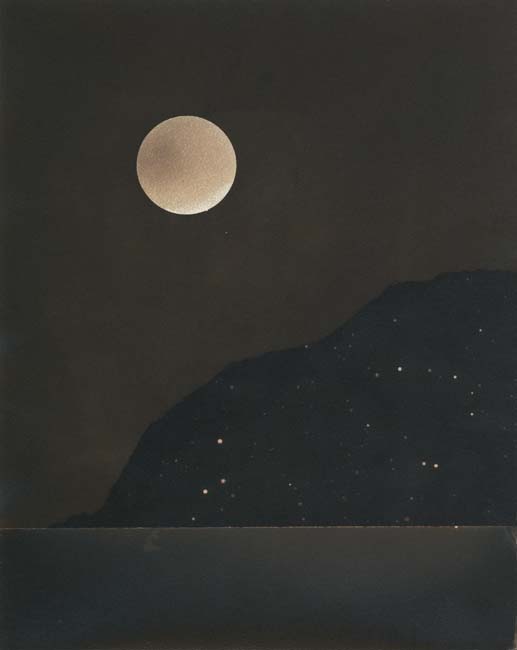

During the height of the pandemic, Claire A. Warden was posting moons on Instagram. Social media was becoming a toxic space, and these photographs inserted moments of awe, joy, and hope into the feed. A universal and unifying symbol to interrupt the divisiveness.

The “99 Moons [@99moonsproject] is a necessary balance that I maintain in my practice,” Warden says. The Phoenix-based photographer creates works without a camera in a process that is expressive, intuitive, and abstract. These one-of-a-kind photographs depicting moons and nightscapes are made in a chemigram-like process in the darkroom, “by contaminating the chemistry,” which brings out different colors in each silver gelatin print.

In her photography classes at Arizona State University, where she received a BFA and BA in 2010, conversations often revolved around the synecdochical nature of photography—a mere moment, a flash, representing the whole. “I was thinking about these ideas: this fraction of a second for a perfect exposure in-camera, the perfect time and temperature when developing film, everything perfectly timed to ultimately get this perfect print,” she says.

Warden began thinking about the finite processes of photography and comparing them to the infinite processes of other media. In contrast to the split second of a camera shutter, “you can work on a painting your entire life,” she says. “Trying to find a way to extend that moment, to make a photograph that is not constricted to a certain time,” Warden found that camera-less processes allowed her to do just that.

“For me, photography’s edge might be related to time,” she says, “and also related to representation. I was trying to push those walls out a little bit and see what I could do if I started breaking some of those rules.”

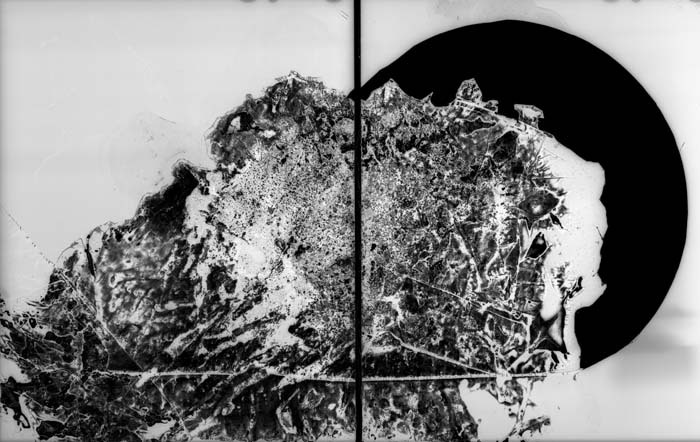

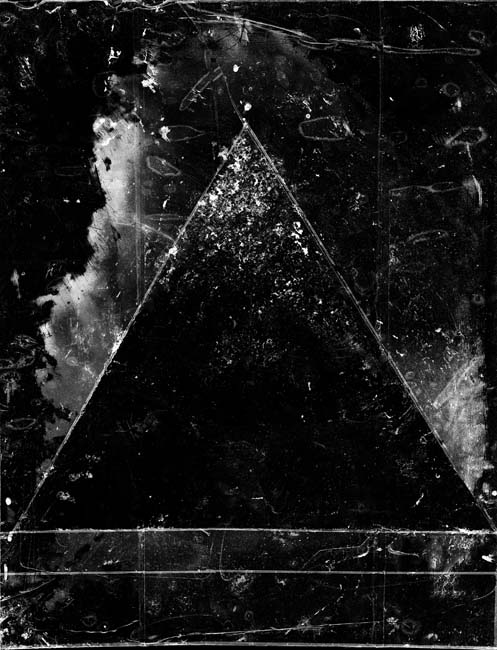

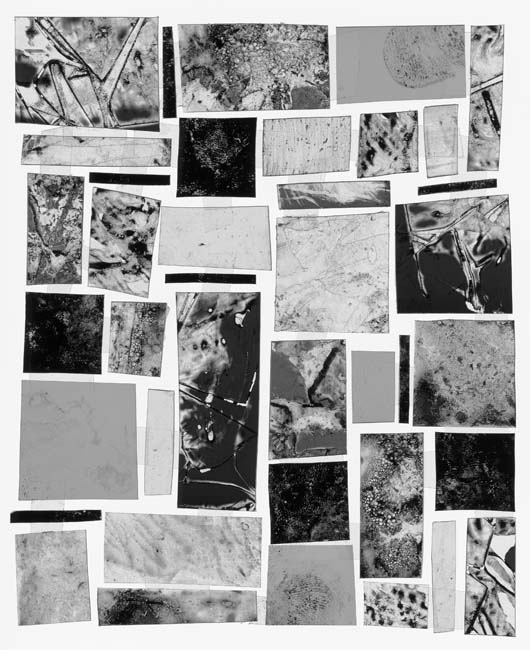

In 2013, she began experimenting with her own saliva to alter the emulsion on developed film. The digestive enzymes slowly break down the gelatin in the emulsion layer, and the result is the remaining biological matter and metallic silver, akin to etching. It takes months for this process to take place, during which time they have to stay wet, “which in Arizona, is a particular kind of challenge,” she says.

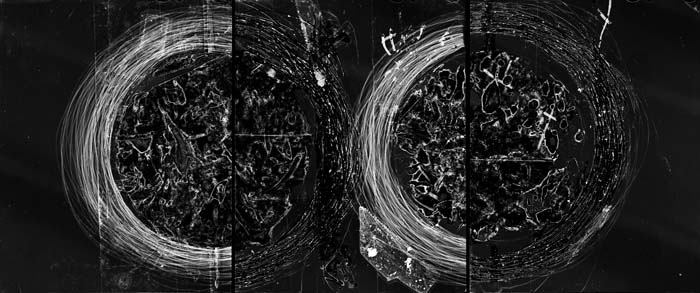

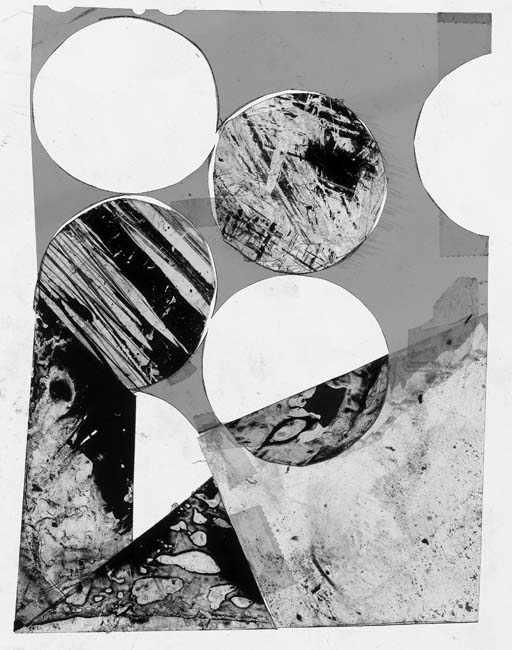

The resulting body of work forms a continuing series entitled Mimesis. The slow process allows Warden to invest in each piece a long regard, watching for interesting forms to emerge, then, finally, fixing the image and performing either additive or subtractive mark-making on top of it.

Born and raised in Montréal, Canada, to parents of multiethnic heritage, when Warden moved to the United States, she was often confronted with the question, “What are you?” from people trying to pin down her ethnicity. Mimesis engages with that inadvertently existential question through biology and abstraction. “The mark-making process [in Mimesis] is really influenced by personal experiences and research based on my questions about identity and racial issues in the U.S.,” she explains. The triptych No. 59 Double Consciousness (2016)—referring to the term coined by W.E.B. Du Bois—for example, relates to Warden’s awareness of being perceived and experiences navigating the differing cultures she belongs to. “I wanted it to be clear that it was two separate worlds and the central piece doesn’t quite fit,” she says.

The series, in its process of intentional mark-making and enzymatic development, confronts both the construction of identity and photography. “It’s quiet in a sense because it’s not telling everybody what this work is about,” Warden says. While the photographs undoubtedly are derived from her person, from her own matter, she says, “It’s not a portrait of me in a traditional sense, what most people likely understand portraiture to be, but I view each piece in this series as a portrait.”

Along with her spouse, photographer David Emitt Adams, Warden just opened a new studio and educational space centered on analog and digital practices in downtown Phoenix. She is currently pursuing an MFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and is experimenting further with the medium of photography along with textiles and analog moving-image work. But now, ten years on from beginning the series Mimesis, she doesn’t see an end to it. “It may be a lifetime body of work,” she says, “because it’s changed so much since I started it, and every piece is new, a step further.”