Center for Contemporary Arts, Santa Fe

February 9 – April 29, 2018

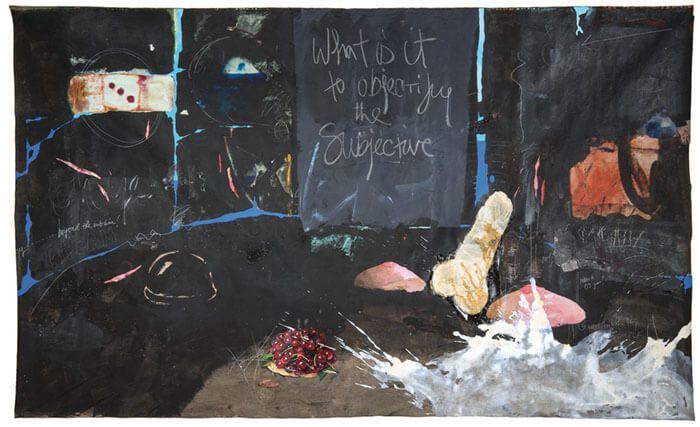

What is it to objectify the subjective…

text from Ciel Bergman’s painting Crimes of Passion

Begun in 1970 and ending in 1977, the late Ciel Bergman’s series, The Linens, is in truth the work of an “emerging artist.” Bergman (1938-2017) was thirty-two when she began these large-scale paintings on unstretched linen, an age in keeping with the beginning phase of most artists, yet Bergman had already had another career. She married young, became a nurse, had two children, and ended her marriage around the time that she enthusiastically embraced the role of artist. It was then that she began to tilt at her own self-assigned windmills relentlessly turning in the shadow of Marcel Duchamp. But what artist living in the twentieth century has NOT been influenced by that gender-bending trickster figure and Prince of Visual Irony?

Duchamp’s presence hangs over The Linens in ways that could have been annoying, but Bergman’s assimilation of Duchamp’s ambivalence towards art and the role of the artist proves a bracing tonic in this exhibition. She accepted Duchamp’s challenge to interrogate illusionism and the questionable presence of symbolism in modern painting; and at the same time Bergman’s own confidence in a personal vision of painting on her own terms gained the upper hand in this series. Bergman’s ongoing dialogue with Duchamp resulted in a multivalent fruitfulness—work that is witty, visually arresting, and full of insights into the possibilities for aesthetic engagement.

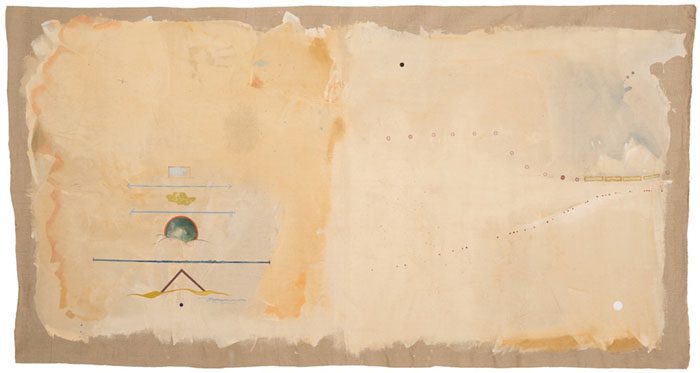

I came to feel that The Linens were akin to contemporary cave paintings that represented maps, environmental affinities, elemental gender distinctions, cellular realities, and symbolic forms that both hinted at a knowledge of art history and a desire to transcend that history with the invention of personal mark making. One of the artist’s visual inventions is something I think of as Bergman’s Phallo-Fallopian Signifier—a sexualized shape that appears repeatedly as The Linens morph from the pure reductive spaces seen in the Spiritual Guide Maps to the intense juggling of the artist’s vocabulary of symbolic forms that comes in the series’ later paintings. Bergman’s symbolism is manifested through color, atmospheric spatial relationships, and precise depictions of objects like a ladder, breaking waves, a blood-stained band-aid, and apertures opening into hints of a distant sky and water. There are also circles, lines, dots, and subtle visual references to images like Duchamp’s iconic “three standard stoppages” and his “malic moulds”; and in one of my favorite passages in the work Crimes of Passion, there is a plate of perfectly rendered succulent cherries anchoring this mysterious juggernaut of painted conceptual relationships. For Bergman, pigment on linen became the perfect gateway to an exhilarating apotheosis of what art, in the end, is all about: the artist’s need to objectify the subjective—because of, or in spite of, what “masterpieces” came before, or, in the painter’s lexicon of ideas, what absolutely needs to be embodied in the here and now. Bergman achieved a genuine monumentality in The Linens, and the work in the Tank Garage is but a fraction of the whole series.

For Bergman, pigment on linen became the perfect gateway to an exhilarating apotheosis of what art, in the end, is all about: the artist’s need to objectify the subjective—because of, or in spite of, what “masterpieces” came before, or, in the painter’s lexicon of ideas, what absolutely needs to be embodied in the here and now.

I can only wonder at the timing of this work’s grand entrance into the narrative of Bergman’s vibrant, passionate, two-fisted, but too-short life. One that encompassed the traditional roles of mother, devoted partner, and committed friend, and extended beyond her quixotic path of artistic foil to Duchampian irony to that of engaged environmentalist who saw the degradation of our planet as a moral failing of epic proportions. This latter theme is something Bergman would go on to address in her later exquisite Antidote series.

Bergman was her own Bride Stripped Bare, her own Large Glass with its inevitable cracks and fissures, and her life’s work incorporated a vision of art that was a kaleidoscope of objectified subjectivities—a painter’s destiny of being double and doubling down on notions of abstraction and representation. Bergman took some of contemporary art’s ambiguous conceptual spaces and painted them in successive layers where personal meaning and self-driven myth gave birth to new incarnations of what painting is and why, after all these thousands of years—from newly discovered Neanderthal cave art that pushes back the dating of our pictorial record, to the one-hundredth anniversary of Duchamp’s last enigmatic work on canvas, Tu m’—painting is more alive and well in the twenty-first century than we ever could have hoped for.