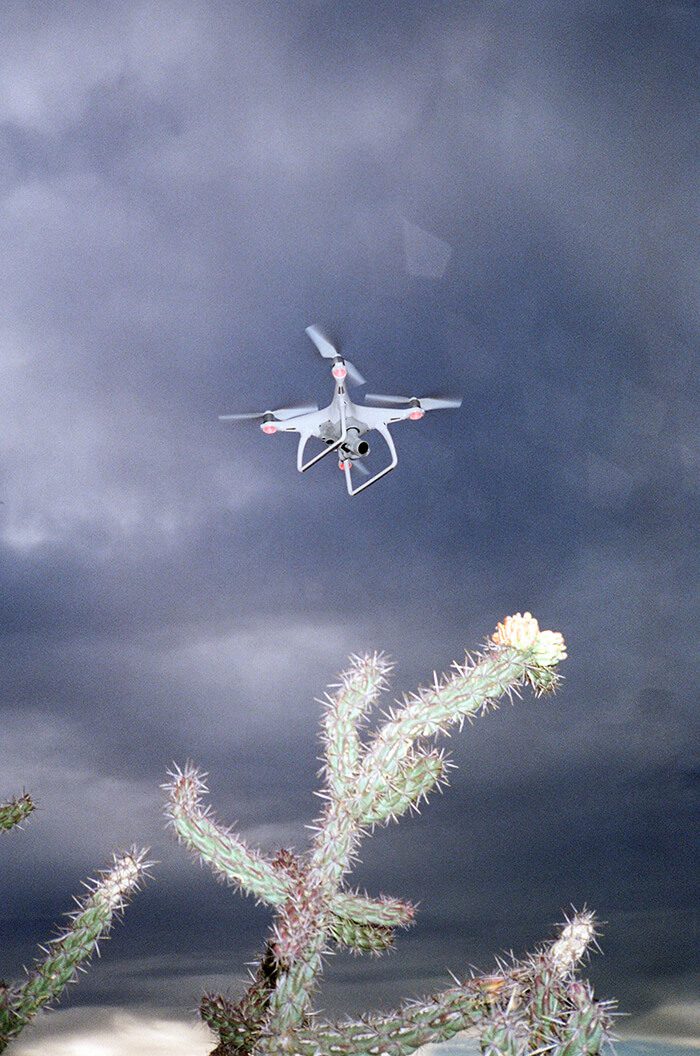

Christian Michael Filardo takes photographs constantly. A hand holds a switchblade near a blurry-socked leg; a drone floats in a twilit sky above a cholla cactus; soap suds cover the windows of a car. A tattooed arm, melted candles, broken glass, leafy houseplants, tainted concrete, dirt, cats, the back of a shaved head. An omnipresent flash, now a nearly obsolete tool since the onset of advanced digital cameras, often provides a slightly garish contrast, sharp shadows, a bit of manufactured nostalgia.

Perhaps because of the flash, the colors in Filardo’s Santa Fe don’t look natural. They’re at once too bright, too vibrant, infused with too much man-made material to look idyllic. Even the photos of flowers have a sharpness that defies serenity. Filardo is not out to capture the natural beauty of the desert so much as to intervene in it and create a mood at once edgy and sentimental. They are documenting their world, their friends, their daily activities, glimpses of symmetry or action that stand out amidst routine. But unlike photographers like Ryan McGinley or Nan Goldin, who also chose their intimates and environs as subjects, Filardo seems more interested in objects—as evidence of human interaction, or as the mise en scène of passing events. Portraits in Filardo’s photographs are rare, and if they exist the faces are often obscured.

Filardo’s photographs are foundational to their practice, but many of their projects span media and disciplines. Their works often involve taking photographs, performing music, curating exhibitions, publishing, and/or creating sculptural installations. The artist doesn’t have a studio, yet always seems to be working, observing a room, composing a shot, looking at books, always ready for a conversation or a story. In February, Filardo and four other Santa Fe artists (Sarah Bradley, Angelo Harmsworth, Drew Lenihan, and Theodore Cale Schafer) opened Etiquette, a gallery and performance space off Siler Road. Filardo describes Etiquette as “a multifaceted art organization looking to facilitate conversation between music and the visual arts, with an emphasis on incorporating the local with the global.” Clayton Porter and I spoke to Filardo in their house, replete with an elaborate indoor potted garden, which they share with other artists and musicians, and doubles as their workspace.

Chelsea Weathers: How did you get into photography?

Christian Michael Filardo: Photomaking has been an interesting path for me. I got my degree in performance art at Arizona State University, and I did some photographic study there as well, but then I sort of fell off with photo for a bit. Then, when I moved to Baltimore for graduate school, I didn’t have a studio space, and I really needed time to work on my art. I was walking everywhere, and my time was basically consumed by walking, so I just started carrying a camera, and it was sort of like a love affair from there.

CW: Is that still how you work?

CMF: Yeah, I carry a camera everywhere. Back then I was shooting digital, but now I’m doing only film.

CW: What made you decide not to use digital photography?

CMF: I love the immediacy and the excitement of digital, but with the film process you can’t see the image right away, so facilitating a certain type of patience or trust in my eye was something I wanted to develop in myself.

CW: What was your performance practice like?

CMF: It was largely self-exploratory, like exploring the ideas of race and gender and identity. I did a lot of video performances and also a lot of music-influenced performances and things like this. I have always gone in and out of that. It’s a funny relationship.

CW: When you were exploring gender and identity in performance, was part of this your own identification as Filipino American?

CMF: Totally. My dad is from the Philippines, and I grew up there as a kid too. And being biracial there is like… people don’t necessarily accept or embrace that very well. But I was quite young. I have a desire to understand that part of my identity in a way that facilitates my having an open communication with my Filipino side and heritage, so my performance was a lot about that, and exploring what it is being a mixed-race person in contemporary American society, because it’s confusing. You’re not white and you’re not Asian.

CW: What’s an example of an early performance that explored your identity in this way?

CMF: Oh, gosh… I did a multichannel video piece where I would basically show these slides that I found of my dad coming to the U.S. on two screens, and I was fully wrapped in saran wrap and just sort of in the middle of the two screens and trying to get out of the saran wrap, so that was like I guess an example of that. [Laughs.] I’m so distant from it now that it’s funny to think about.

CW: You still perform music, though.

CMF: Very often, yeah. My musical performances are largely based around voice and clarinet, and I’m much closer to that these days. I’m still exploring contemporary identity but more from a millennial standpoint, I guess.

CW: It seems like there’s a connection between your earlier performances and your musical practice, but it isn’t totally obvious.

CMF: So I wanted to get a saxophone, and I took a bunch of stuff to the pawn shop and I sold it all. And then I said, “Do you have any saxophones?” and they were like, “No, we only have clarinets.” So I bought a clarinet. This was two and a half years ago, now. So I bought that, and I started practicing, mostly just trying to figure out free improv or free jazz, and then I started to learn funny facts about how the clarinet was in my life. Like my dad told me that my grandmother used to play it in the brothels in the Philippines when they needed money. Then someone told me the clarinet is the instrument that sounds most like the human voice, so I started to get really interested. I really like Meredith Monk and Robert Ashley, and I started exploring how I could use the clarinet as a voice in conversation with myself. I would play the clarinet and I would also say something like “received text message at three in the morning, hello” or “fall asleep after reading text message” or this kind of thing. And it’s all very improv, just flying by the seat of your pants or adding elements. When I play, there are usually strange objects around, so I’ll play the clarinet, pick up a thing, put the thing down, so there are object-based interactions in the performance too.

CW: What do you mean when you say you’re interested in millennial identity?

CMF: We spend so much time on our cell phones, and I think that’s a core, defining thing for the millennial. Social media is insane: we participate and communicate and share so much. I’m very intimate with my phone because of these relationships I have with people where we communicate via text message and have these conversations that are like that [snaps finger]. Sometimes it’s good to not always be absorbed in this, but we exist this way. At least I do. My phone is my alarm; my phone is my communication, all of these things. So when I reference that in my musical or spoken work, I think it’s about trying to understand these relationships in a physical realm. We have friends that we’re intimate with, people we desire, and we communicate in this hilarious way, and we can’t always be present.

CW: You have put sound in your photo installations, too. Are your music and photography complementary practices that inform each other?

CMF: I think with photography I’m always trying to distill images down or pare them down so they have a sequence, and I don’t believe that’s very different from making a musical score or a musical composition. The sequence doesn’t necessarily have to be linear; it can be very abstract and non-linear, but I think that photographs can be like notes that have a conversation or make a conversation. So they’re very similar in that way. I also do think that photographers perform too, and to be given the power of the camera and basically being the designated person who is looking at something is not dissimilar to being a person with an instrument.

CW: When you carry your camera around, does it affect your social interactions?

CMF: I often have a hard time taking pictures of people if I’m not intimate with them, but I do like to carry it around constantly, because you never know when you’re going to run into something. And also I have relationships with some objects that I see every day that I want to document every day, or think about at least. And so, yeah, it does change how I socially exist in the world, because a lot of the photos are pretty flashed out. So I get fairly obnoxious, and if somebody is like, “What are you doing?” I’m just like, “It’s fun. I’m having fun.”

CW: A lot of your photographs have a very everyday quality, which makes sense because you’re carrying your camera around and documenting your everyday life. They are also very carefully composed, but the things you choose to photograph often have this junky, kind of ramshackle quality to them.

CMF: Early on, I found that I was constantly looking down for some reason, and things I would be interested in would be like [points to floor] this bundle of wires in a bag. And I’d think, “That’s strange: there are three colors there and all these weird lines happening, so maybe I’ll just bend down and take a picture of that.” Then that sort of evolved intomy going out at golden hour and seeing like—I’m really into plants, so anything that is back-lit, that I can flash from the front, I just get really into that. And I’m really interested in anything being subtly askew or off, even if it’s something that is arguably fairly normal at the same time.

CW: Obviously a lot of your practice involves your just being out in the world, but in terms of your home and not having a studio, how does that work for you in your domestic space?

CMF: It’s crazy. Luckily I work at a photo bookstore, so I will get books constantly, because they’re either damaged or I’m interested in them. I’m just constantly checking this stuff out all the time. [Flips through books.] A lot of my practice is really just that, and I try to go on a walk every day and designate that I need to shoot like six rolls a month. If I’m shooting less than that, it’s like I’m wasting my time. And my roommates are both musicians, so there’s sort of a constant workflow here, and we have the other space [Etiquette] as well, so if I’m not here, I’m there. It’s like a snowball.

CW: When you are showing your work, what is your preferred mode of display? What are some different ways you experiment with the physicality of the image?

CMF: I’m a strong believer that a photograph can be anything, pretty much, and the idea of limiting it to two-dimensional space is something I’m interested in playing with but also rejecting. So for a second I was putting everything on metal, and I can show you some of these little guys. These are from a show in Baltimore.

CW: It feels like a tintype.

CMF: Totally. It feels like it’s some nice object, but it’s not. I’m interested in showing things really low to the ground, on the ground, covered in dirt. There’s this idea that photography is this visual myth and that you basically see what’s here [inside the frame], and then there’s all this other stuff obviously existing in the periphery. I’m interested in abstracting that. What happens when you just take this [grabs some dried yellow roses and sprinkles the petals onto the photo], and what does that mean?

CW: You like to place organic materials with your photographs: you rested two photographs on top of watermelons at a group show at David Richard last year, and at Etiquette you displayed your photos in the leaves of houseplants. How did that start?

CMF: I think I first got really into watermelons specifically in a visual sense from a Frida Kahlo painting of watermelons. I was taking this class called The History of Mexican Photography, and we talked about watermelon metaphors. I was really quite interested in this thing that represents fertility and sex and femininity. The piece at David Richard had photographs from inside Dan Flavin exhibits. So there’s this strange organic object that you can grow, that everyone can grow, and it’s supporting this sort of bootleg of a very high-art thing. It’s just this weird conversation I’m interested in having. I think plants are pretty punk. You put a plant with something, you have access; it’s not above anyone. You know what this is. It makes the relationship with the viewer a little bit softer and more exciting, I think.

CW: Etiquette is one of only a few spaces in the Siler area. Do you feel like there is starting to be some growth and a feeling of community there?

CMF: I feel like there’s great potential for a really good community. One thing that I do find—and not to be too critical of Santa Fe or anything—but I do find that people are too nice. I’d prefer there to be more critically curated things, or things that felt a bit more thoughtful to me. But I think, yeah, there are more things that are happening that I’m excited about.

CW: You just curated a show, 8 Photographers, at Etiquette. How does that exhibition cohere for you conceptually?

CMF: 8 Photographers was basically an experimental color photography show. We had two weeks to put it together. One thing we have going at Etiquette is that the space has these high ceilings and a lot of dynamic presentation, and so I wanted to get some fairly different people in there and have it be focused around the idea that photography isn’t necessarily conventional. It can be conceptual and sculptural. Also, it can communicate with itself and have that conversation with vibrancy and color and abstraction.

Clayton Porter: Now that you have your own space, do you feel like you’re moving away from showing in other spaces?

CMF: I would love to show in other spaces; it just depends on the work. If they’re down to let me put a watermelon on the floor, I’ll do it. I would like to continue showing in spaces that are well prepared to show work on the walls—and also maybe have the potential of selling work.

CP: Do you see that as being a possibility, with your work being, like the watermelons and photographs, commodified but also not?

CMF: I’ve sold work through books and prints. Angelo Harmsworth just put my first book out. I can show that to you. We did this together, and he made an hour and a half of musical compositions that also come with it. It’s called The Voyeur’s Gambit. We’re both really into chess, hence the gambit thing. It comes in this little black pouch, and it’s thirty 4×6 photos on a ring.

CW: Did you construct these?

CMF: Yeah, we made them and designed them. It’s just a loop of thirty pictures. I find the sequence does matter, but it doesn’t necessarily in concept. This just came out two weeks ago. I’ll also do print sales: say, if you want a print, I’ll print one in a certain size and edition. So, yeah, I’d like to sell work. I’d like to figure out how. I remember I was taking this book arts class, and the professor said that Baldessari said that every artist needs a “small.” A small was just like a small item you can sell for a good amount of money to help you eat, and I’ve always admired that and wanted to figure out how to get the right small.

CP: Do you think this is a lifelong journey, to try to do that?

CMF: I think it’s like things have been. I think it’s a lifelong journey, for sure. It’s interesting. I do this because I want to figure out how to present the work and communicate and show people the work. Just trying to communicate with pictures in as many ways as possible.