The virtual-reality installation Carne y Arena, the brainchild of acclaimed director Alejandro G. Iñárritu, is an unforgettable twenty minutes of walking in migrants’ shoes at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Carne y Arena (Virtually present, Physically invisible)

October 30, 2020-January 30, 2021

The Hangar at Stanley Marketplace, Aurora, Colorado

Many of us feel secure in our liberal ideals in denouncing what’s happening at the U.S.-Mexico border as Mexicans and Central Americans fleeing violence, drugs, and gangs attempt to cross into supposed safety. But we can’t really know the physical, emotional, and mental toll of that attempt at a new life; most of us can’t walk the proverbial mile in a migrant’s shoes.

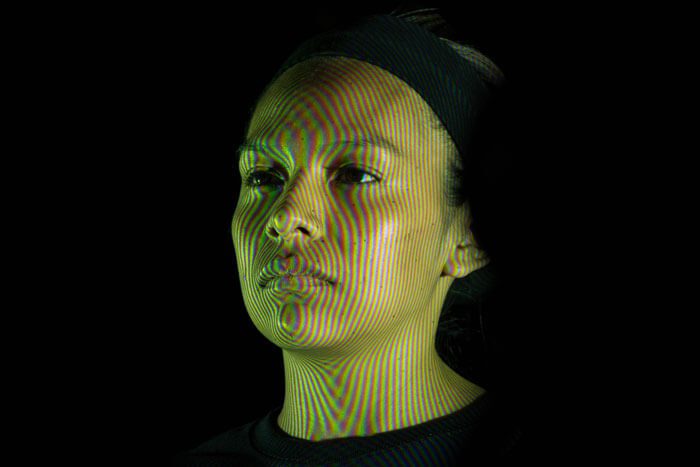

Alejandro G. Iñárritu, the renowned director behind Birdman (2014) and The Revenant (2015), has changed that dynamic into a masterful virtual-reality experience called Carne y Arena (Virtually present, Physically invisible). It is an unforgettable twenty minutes of immersive art. Even beyond its undeniable success as a vehicle for creating empathy for migrants into the U.S., Carne y Arena is a beacon of things to come, showing art lovers how immersive, experiential, three-dimensional art can transport them into unfamiliar worlds. Virtual reality upends the paradigm of the white cube–and is just as aesthetically vital.

Each who enters the small gallery where Carne y Arena is projected is likely to have different takeaways. The time in the experience rushes by, at least it did for me. I began to feel tense the minute I entered the “detention cell,” where shoes and socks are removed and participants wait for a loud alarm signaling the door to the VR gallery. The gallery is covered with sand—not unlike the desert floor. Adding to the sensory input are the backpack, heavy VR goggles, and headphones everyone must wear. As soon as the lights went out and the gallery assistant started the projection, my breathing grew a little ragged. All around me were figures seemingly heading through a vast desert landscape toward a destination—they looked spectral and real at the same time. Then the tension was heightened by bright lights and ominous sounds of helicopters, Border Patrol truck headlights, barking dogs, scuffling, screams, pleading dialogue in Spanish and English, and a general atmosphere bordering on not just uncertainty, but terror. Whenever a BP agent yelled, “Hands up!” or “On your knees!” I was ready to comply.

Virtual reality upends the paradigm of the white cube–and is just as aesthetically vital.

The feelings of disorientation and distress were quite visceral for me because I was too absorbed to stop and think, “This isn’t real.” As viewers soon learn, however, the scenes are based on the actual experiences of undocumented individuals. As the experience unravels, it’s not always easy to comprehend the multiple narratives, as far as who’s traveling with whom, from where these travelers of varying ages have come, and how they’re hoping to make it to safety. What is evident, though, is the exhaustion and fear on their faces and in their movements, borne of dehydration from days and weeks of walking, as well as uncertainty about what lies ahead.

The stories become clearer after exiting the gallery. A darkened room is lined with shadow boxes that hold the photos and biographical texts of several of the migrants. For instance, a middle-aged man describes the unlivable conditions he’s leaving behind, a young man recounts being separated from his brother, an older woman recounts how fellow travelers tried to revive her, and a BP agent expresses his compassion for all those who attempt the harrowing trip.

In creating the touring installation in collaboration with cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, the ILMxLAB, and producer Mary Parent of The Revenant fame, Iñárritu listened to the haunting stories of a number of refugees, then asked several of them to reenact a fragment of their journey so that it could be captured on film. In an artist’s statement, Iñárritu explains he turned to VR because of its evocative storytelling power and because he wanted to “break the dictatorship of the frame.” With VR, instead of mere observation, the visitor has “a direct experience walking in the immigrants’ feet, under their skin, and into their hearts.”

Carne y Arena premiered at the 2017 Festival de Cannes as the first VR project ever included in the official selection. The same year, Iñárritu received a special Oscar for the work. It is now on a multi-year international tour.

For someone like me, with a liberal stance on immigration reform, to spend a short time immersed in an uncanny VR version of border crossing was enough reason to see Carne y Arena. And for anyone seeking a glimpse into the future of art exhibitions, Iñárritu’s work is an outstanding example, offering another worthy reason to experience it.