The Museum of Modern Art and MoMA PS1, New York

October 21, 2018–February 18, 2019

In Santa Fe, Bruce Nauman feels to me like an invisible figure. I know he lives near, I know he frequents the same diner I frequent, I question every tall, bald man in my vicinity, but I never see him. He is shadowy, reclusive, distant. To see his retrospective at MoMA (scanning the crowd at the opening, asking, “Is that him? That?” about the same bald man, who was never him), is to be confronted not with disappearance but with the artist’s body.

Spanning a floor of MoMA and the entire labyrinthine MoMA PS1, Disappearing Acts eventually centralizes the body of the living artist. Several wall-sized screens, one filmed in 3D, show Nauman in his studio, jeans and t-shirt, walking like he once did in his video Walk with Contrapposto (1968), up and down the room toward the camera and away. His top half is on a different time loop than his bottom, so he wobbles, dances, the uncertainty and the carefulness of each step heightened. In Contrapposto Studies, i through vii (2015/2016), we see the artist has aged, the artist who disappeared, who faded into the New Mexico sunset in the 1970s. He’s bald, he has a belly. That belly. So pronounced. Something outlined beneath the t-shirt—a microphone? A colostomy bag? Some other marker of his battle with cancer?

This recent work offers us the fragility and vulnerability of the aging human body in the midst of a body of work that gazes unflinchingly into all those things that seek to control, corral, and damage the human. His ongoing play does not shy from the darkness of the state, surveillance, torture, terror. A steel cage within another cage with a narrow open door offers itself up for viewers to enter, wherein they find themselves able to move only sideways, if at all. The idea of circling the entire cage, the time it would take, the time one would remain trapped, is its own imaginary form of terror. The use of video surveillance in Nauman’s corridor works, like Going Around the Corner Piece (1970), only allows you to glimpse your own back in the monitor as you round the corner. (I kept wondering, “Why do I want to see myself?”)

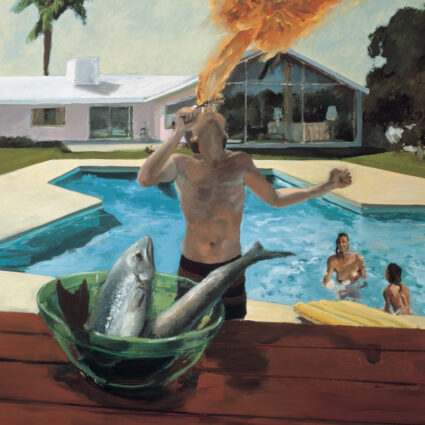

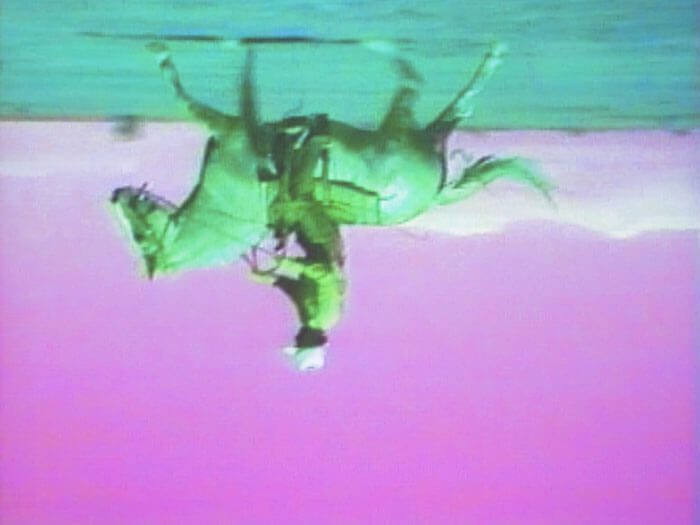

Even the moments in his work that give a glimpse of freedom—like Green Horses (1988), a two-channel video installation of a man (the artist, again) on a horse, in the open New Mexico landscape—are constrained by shapes, repetition, by the narrow tight paths he guides the horse through. Bruce Nauman: New Mexico artist? Certainly he draws on the visual language of New Mexico: the ranch and its activities (fence-building, horse-riding), its attire (jeans, boots), the taxidermy models ordered from ranch supply catalogues.

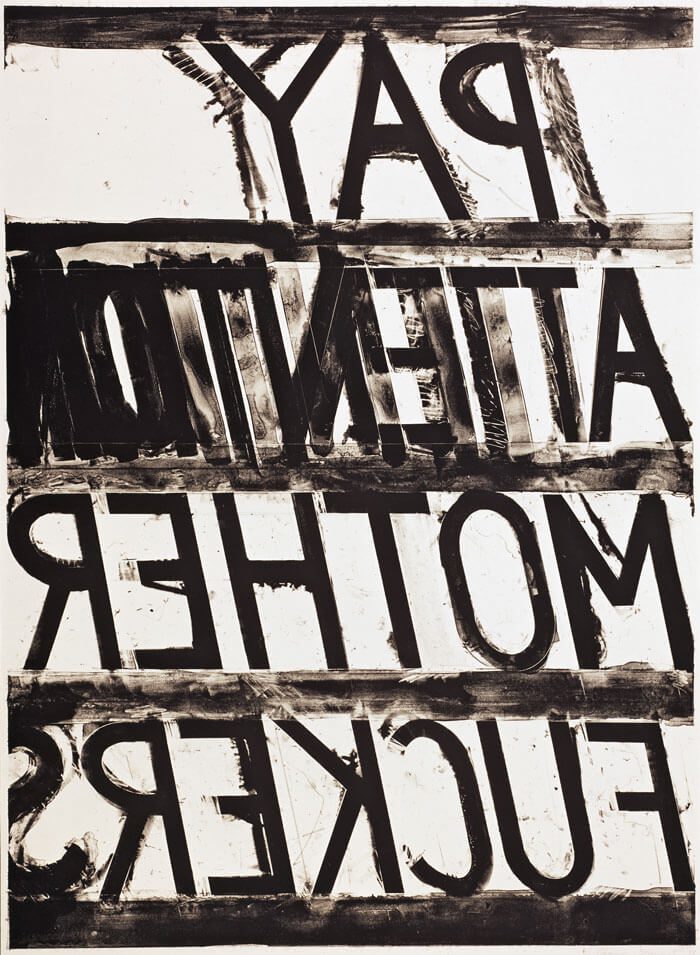

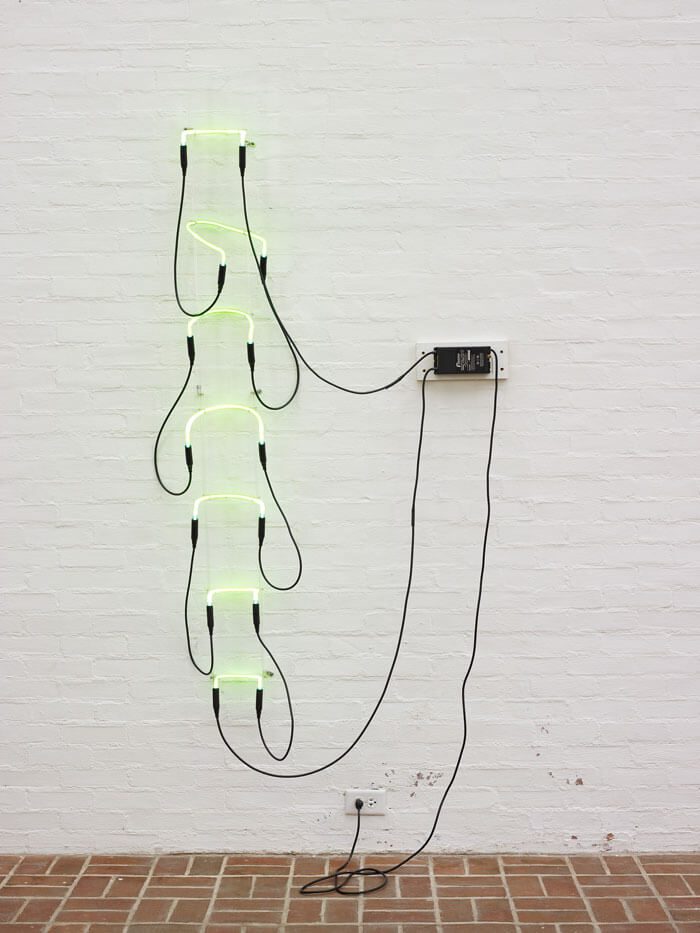

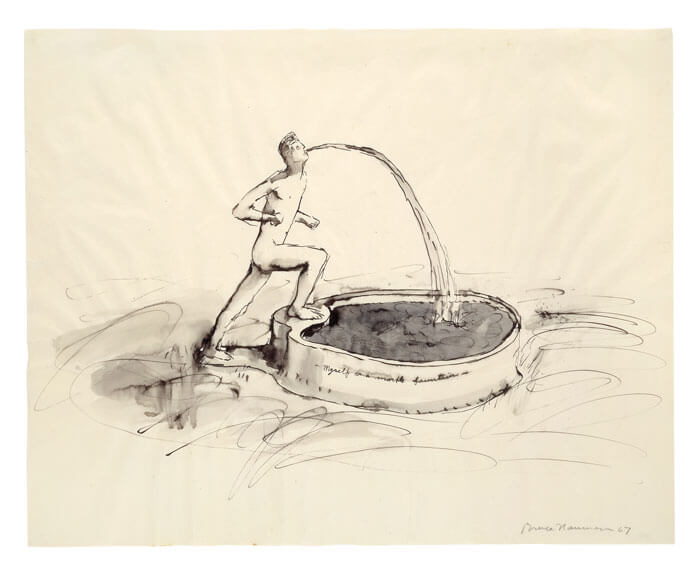

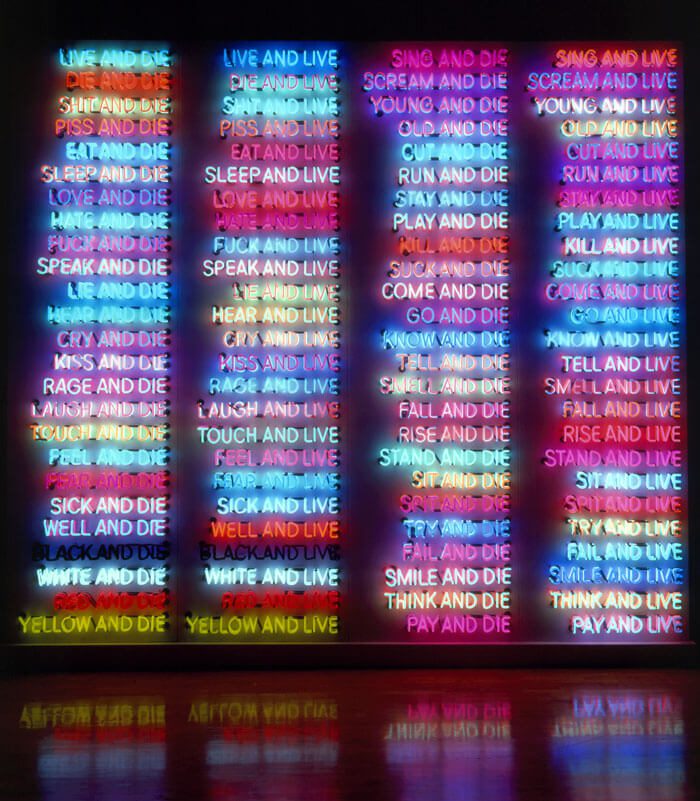

Nauman’s work visualizes the body in space, with a dancer’s feel for the intricacy of small movements. His subjects are often acts of making: a video of him bouncing balls in a square taped on the floor, or tapping the sides of the square with his feet, testing the waters, testing out possibilities, the act of experimentation, of play, the process itself as the product. Making work about making his work is also then about repeated trials, repetition, the days of the week recited in a room in varying tones. Repetition is at the heart of his work about language and power: gravestones carved with the seven deadly sins overlaying the seven cardinal virtues; talking heads of a young black man and an older white woman, telling the viewer they were a bad boy, a bad girl, reciting a script in different registers until the words could mean anything. But the work’s aggression, or the viewer’s resistance, is not always so sinister in tone. It also comprises the humor of a boy in a bathroom stall, lighting up sexual positions in neon (what Catherine Lord, in the exhibition catalogue, calls “flatulent masculinity”); the puns, so many puns, dad jokes, things you just don’t want to laugh at, language games: All Thumbs (1996). Disappearing Acts shows the life of a restless and obsessive mind, reflecting on the role of the artist and the state of human vulnerability in a constricting, incarcerative society.