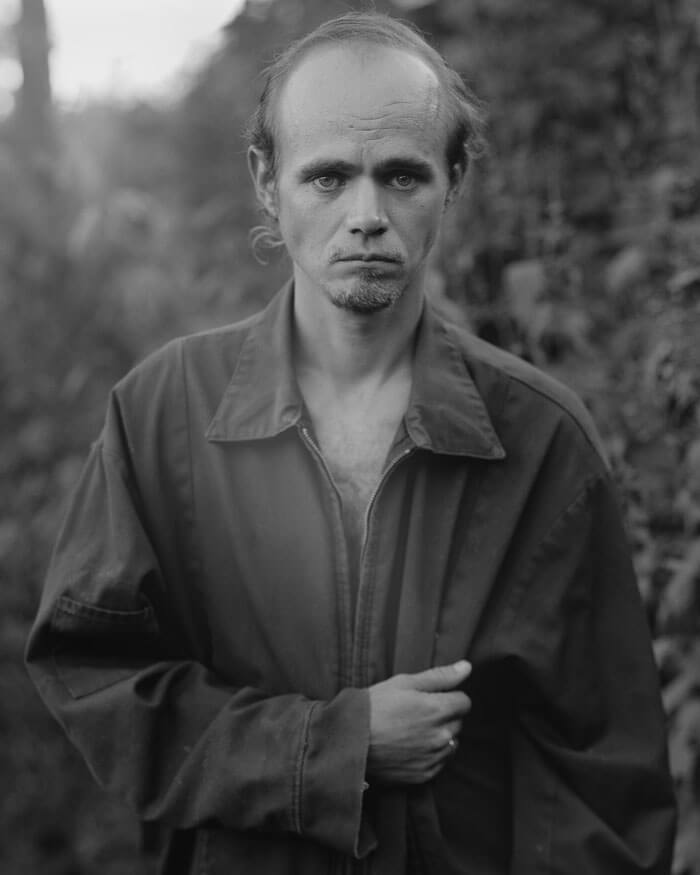

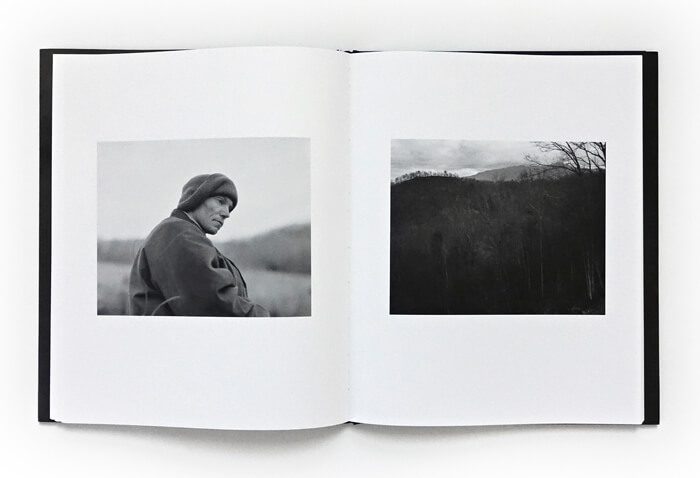

Jasper is the first book from photographer Matthew Genitempo. While the images were made in the Ozarks, they recall an atmosphere of rural America more than they reflect a specific place. The name Jasper, too, has a particular generality: it could refer to a number of sparsely populated towns across the United States or could be a fitting name for any of the men pictured in this book. A place name, a person’s name, really it doesn’t matter. Jasper is evocative of a feeling.

The fantasy of running from society is a desire separate from the reality of living at its edges. Both are depicted here, and the tension between the two suspends Jasper in a state of stark buoyancy. The paleness of smoke or a motion blur or the whiteness of a reflection gives the black and white images a dream-like haze. We are not so much put into the world of those who inhabit these areas as we are put in the position of an outsider, one traversing and stumbling upon them. Dark ridgelines of bare trees and rolling fog become refrains between images of tangled landscapes and portraits of the men Genitempo encountered. We see the details of their rough hands and the eerie timelessness of their cobbled-together homes. They live in the places where the density of the forest ends, buildings tucked in small clearings, away but not always beyond powerlines. We hang at the edges, where the cut of a tree line indicates both wilderness and the man-made nature of that boundary. We seldom glimpse past it. Only the domestic scenes feel over an edge, resonating with isolation and anxiety.

A run-on poem by Ryan Paradiso opens the book and moves in parallel, its images foreshadowing the photographs. It is a block of text without breaks or punctuation—or at times coherent wording, evocative rather than descriptive: “This is not a story of ruin for ruin has no ghosts it is a story that ends with a waterfall deepening like two closed eyes in the throes of loss or bliss it crawls…” Though the analogy to poetry is clear, Genitempo cites poet and land surveyor Frank Stanford as inspiration. Some photo books are catalogues of images, and others read like poems. The latter rely on photographs for a special type of description that is less concerned with the agendas of singular images and exploit what is fundamental of a photobook: sequence. Like the lines of a poem, images are read cumulatively and in proximity.

In the penultimate photograph, a cascade of luminous foliage descends on the folded frame of a shirtless man pulling himself in or out of a tent. It is both gorgeous and grim, the beauty unresolving of the pain.