Bill Gilbert’s ceramic works at the Anne Cooper Occasional Gallery share with us his relationship with the land and the “appendages” we employ in our experience of the world.

Anne Cooper has had a long career in the arts, making and showing her own work—including indoor and outdoor installations using wood, steel, beeswax, clay and, at times, sprouting seeds and growing grass and, more recently, finely detailed pencil drawings of seeds and grasses—but also participating in events and organizations in her local art community. About fifteen years ago, rather serendipitously, she started using the meditation room adjoining her home studio for exhibitions of other artists’ work on an irregular basis, eventually naming it the Anne Cooper Occasional Gallery (or ACOG). Now, several times a year, she invites artists to exhibit their work in the small but serenely beautiful space, and hosts an early-evening viewing for those fortunate enough to be on her mailing list. The gathering is not an “opening” because the exhibition typically comes down immediately after the event. The works are for sale but Cooper doesn’t take a commission or handle transactions, which are the responsibility of the artist. Her focus is on artists who are relatively unknown or who are established but may not have gallery representation and, perhaps most importantly, whose work she respects and believes deserves exposure.

Last fall, Bill Gilbert showed some of his recent clay works at ACOG, which made for a particularly evocative evening since he and Cooper share a strong background in ceramic arts and a passion for experiencing the natural world through artmaking. Gilbert is well known for his decades-long focus on the relationship between humans and place, making art with native materials of Northern New Mexico, where he lives, to “develop an intimacy with the land,” or creating “a portrait of place by walking the surface of the planet” at sites across the United States and internationally. Since 1981, he has explored how we perceive and interact with the land and with a place, whether by bringing nature into the gallery space (literally or via various media), working outdoors to create site-specific installations from locally sourced materials, or guiding his students on trips to Land Art projects throughout the American Southwest. In addition, during this time, he was a professor of ceramics at the University of New Mexico where he also established the Art & Ecology and Land Arts of the American West programs, and authored two books, among many other endeavors.

His 2019 book Arts Programming for the Anthropocene: Art in Community and Environment addresses the need for updated curricula for upper-level art education programs so that students may be better prepared for living and working in the age of the Anthropocene. Gilbert describes this age as a new epoch in which humanity has intervened in the environment to the point that we have fundamentally altered the earth’s ecology. His art practice has become one that enables him to “act as a human in a manner that doesn’t add to this problem…and instead builds a relationship with this…unknown ecology that we have messed up.” One way he does this is by walking the land and then representing his experience in maps, videos, sculptures, and other forms and media. His activity of walking is the physical embodiment of this commitment and his primary art practice. The artworks he creates to record these walks are secondary to that practice, and serve as a means of sharing his experience and inviting others to become more aware of their own relationship to the land, a place, and our planet.

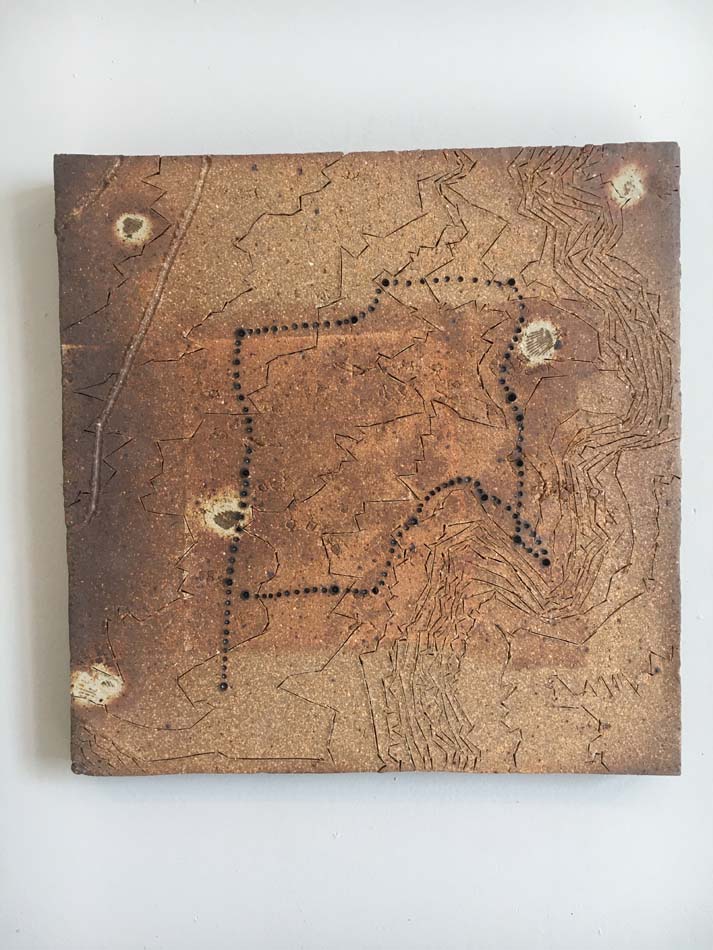

At ACOG, Gilbert exhibited seven “maps” based on two series of walks: For John Wesley Powell: Attempts to Walk the Grid (2005-2011) and Celestial/Terrestrial Navigations (2012-ongoing). The works shown here document these walks at sites around the American Southwest, during which he set out to navigate the land using USGS grid lines and GPS calculations, and tracing patterns of stars created by ancient cultures onto the contemporary landscapes. The maps are made using clay Gilbert harvested himself from locations in Northern New Mexico, and average about sixteen inches square and one inch thick. Lines incised into their surfaces render the elevation contours on USGS topographical maps of the area. Small, shallow holes form black dotted lines indicating the routes of his walks (due to features of the landscape, they necessarily diverge from any straight path from point A to B) and the patterns of “star points” on the ground that mirror constellations in the night sky overhead. The clay panels are wood-fired, resulting in their somewhat misshapen square shapes and mottled glazing that ranges in hue from deep smoky brown and rich ochre to terracotta and a kind of bleached sand. Their surfaces are rough and studded with imperfections and bits of soil. So although these works function as maps of places and depictions of Gilbert’s walks, that is, as representations or images, they are also literally pieces of ground, real slabs of earth that bear the physical marks of human intervention. They invite us to consider the impact of our presence on the land and on the natural world as well as to recognize how nature’s physical inevitability can disrupt and alter our best intentions and humankind’s tendency toward rational order and systems.

Also included in the exhibition were four wall sculptures Gilbert calls Appendages (all 2023). The emailed invitation explained that they are based on the shape of a polishing stone given to him by Acoma Pueblo potter Mary Lewis Garcia. Polishing stones are tools used for burnishing pottery to a smooth, glossy surface, and are themselves necessarily very hard and smooth. Ideally, they fit comfortably in the hand so as to become like a part of it, extending the practitioner’s sense of touch and contact with the work. With these ceramic sculptures, however, while Gilbert has retained the shape of his polishing stone, he has scaled up its size from two to fourteen inches into a biomorphic form that may suggest part of the human body, or even a torso. Simple in shape yet richly glazed and wood-fired, each sculpture has its own complex palette and texture. Gilbert has abstracted the form of the hand-held tool into “appendages” with allusions to human form, detaching them from the object on which he based them and creating sculptures that exist independently of it. Indeed, the polishing stone, if we know about it at all, is absent here and present to us only as an idea. While these works conceptually and formally relate to that idea, we may experience their physical presence as engaging aesthetic objects without knowledge of that relationship.

A third group of works was a set of twenty bowls displayed on a long pine shelf. Gilbert doesn’t claim to adhere to the age-old tradition of Japanese tea bowls but, like the centerpiece of the Japanese tea ceremony, his bowls have no handles and are made to be held in both hands (visitors were welcome to pick them up). They are crudely crafted with subtle variations of shape and emerged from the kiln with unexpected colors and textures that give each one a unique appearance and tactility. As vessels, these bowls are clearly utilitarian and more conventional than Gilbert’s other clay works shown here. And even though he intends that in their use they suggest an intimate dialogue with the human body—they are brought to one’s mouth with two hands and as bowls or cups have “lips” and “feet”—they function sufficiently as aesthetic objects that directly engage our senses and manifest the inherently unpredictable beauty of wood-fired clay.

In Cooper’s introduction to Gilbert’s gallery talk prior to the main event, she read from an early journal entry about the uniquely speculative and uncertain process of making and firing clay works: “Working with clay is audacious. At every stage disaster can occur, broken greenware, cracked bisque, glaze that runs, or doesn’t respond correctly, a pot can blow up and destroy everything in the firing…. Ceramicists are patient and optimistic; otherwise they need to do something else.” Gilbert reinforced her observations in his talk as he described the often-explosive results of salt firing, the unexpected colors and textures that occur with wood firing, and how a week-long reduction firing in a wood kiln requires constant attention from a number of people to keep it fueled. Unfamiliar with the techniques of clay work, I was struck by this untamable process and the fact that even the most experienced and skilled ceramicists, like Gilbert and Cooper, cannot fully control the outcome. They actually seem to anticipate and relish the many unforeseeable factors and results that determine the character of each work.

The intentionally accidental aspects of Gilbert’s clay works may be regarded as consistent with his walks on the land, which also are enriched by encounters with the unexpected and by the activity’s transformative effects. As potter Mark Hewitt wrote:

I think that wood firing symbolizes wildness, and that in our practice there is primal poetry, a raw, elemental directness, and a sanctifying of natural materials and processes. We take the earth. We light a fire. We make beauty. Our pots are landscapes; they are about particular places, particular clay deposits, particular trees and forests… Wood-fired pots are not decorative, pleasant, and safe. They are secretive and possess a refined agency that allows them to inhabit our consciousness as symbols of our relationship to the earth, as reminders of our history, and as talismans of hope.

I imagine Gilbert would agree and intends that we experience his works not only as objects to be explored visually and tactually, but as embodiments of the process that gave them their character and, as he says, adds to them a “physical imprint [as] a marker of a specific moment in time.” Such an experience may lead to our own sense of agency, which allows us to incorporate the unpredictable and the ephemeral, even a wildness, into our relationship with the natural world.

Gilbert’s three groups of works shown here, while at first appearing unrelated visually and even conceptually, are connected in that they all seem intended to explore—and to remind us—that our relationship with tools such as maps, polishing stones, and bowls is not merely one of utilitarian purpose but a physical, bodily experience. Further, in the right hands, they may become aesthetic objects with no use at all other than to give us pleasure and perhaps invite us to reconsider how we relate to them and to the world around us.