Danny Lyon—photographer, filmmaker, ally of marginalized people, and heart-on-sleeve wearer—is celebrated in an Albuquerque Museum exhibition featuring selections from a prolific sixty-year career.

“Is what I see the same as what I feel? What I feel, is that the same [as what] I am? Is that what this was all about? Leaving behind a copy of what I saw?”

—Shadowman (2010), a short film by Danny Lyon

Surveying Danny Lyon’s creative career is overwhelming—the emotional weight of his impressive and extensive body of photographs and films is staggering because Lyon has, for more than sixty years beginning in the early 1960s, restlessly sought to document a diverse range of human-centered subjects that include civil rights activists, outlaw bikers, incarcerated individuals, and those of marginalized communities throughout the world.

Lyon was born into a German Russian Jewish immigrant family in Brooklyn in 1942 and raised in Queens, New York. His father, an ophthalmologist and amateur filmmaker, spurned his son’s film and photographic interests. By his early twenties, while attending the University of Chicago, Lyon had embarked on his photojournalist career as the staff photographer for the youth-led, direct-action Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC. Through his involvement, he met SNCC co-founder Julian Bond, future Congressman John Lewis, and Dr. Martin Luther King. Lewis and Lyon would remain lifelong friends until Congressman Lewis died in 2020. Lyon’s photographs from this period remain a primary record of this fundamental struggle for equality and racial justice.

An adherent of the New Journalism championed by writers Hunter S. Thompson and Tom Wolfe, Lyon next chose to immerse himself in outlaw biker culture (by participating directly as a member of the Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club) to produce one of the most recognized bodies of classic street photography—his influential photo book, The Bikeriders, published in 1968.

Beginning in 1967, Lyon spent fourteen months embedded in six Texas prisons with nearly unrestricted access granted by the Texas Department of Corrections. During his tenure, he intimately documented the lives of incarcerated individuals on death row or life imprisonment while exposing the grim reality of those forcibly laboring at prison farms—now viewed as an extension of the Deep South’s historic slave economies. This experience led to his revelatory 1971 book Conversations with the Dead, which brought awareness of the systemic brutality of the burgeoning corporate prison-industrial complex. In addition, Lyon would form close relationships with some of the inmates he had befriended inside, returning to these prisons to bear witness to the lives of these individuals in films and non-fiction books, including Like A Thief’s Dream (2007).

Other significant bodies of work would follow, including his haunting memoir of demolished 19th-century buildings of New York City’s Lower Manhattan, an area razed to make space for soon-to-be-constructed World Trade Center’s Twin Towers in The Destruction of Lower Manhattan, published in 1969.

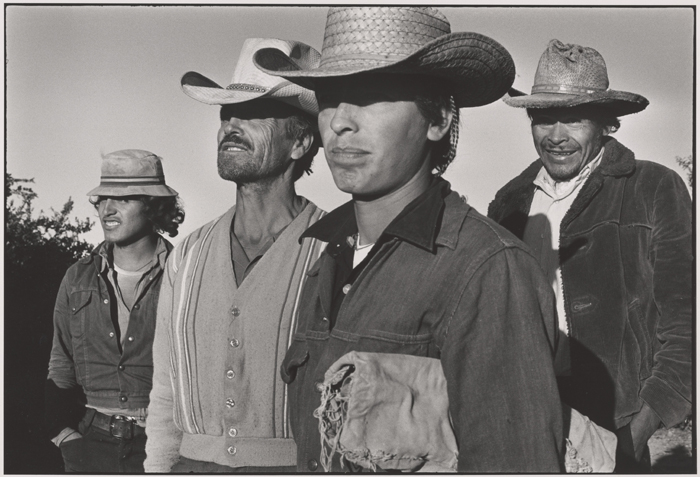

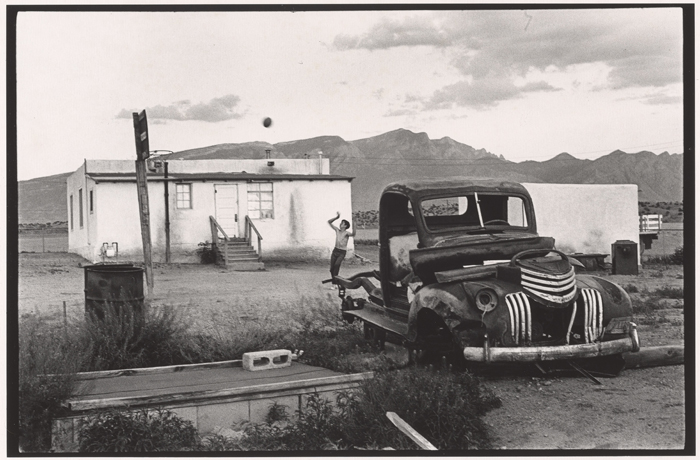

Like his friend and mentor, the formidable photographer/filmmaker Robert Frank, Lyon made raw, poignant personal films of and with the help of his own immediate family and friends (occasionally incorporating footage and photographs filmed by his father, Ernst). Other films document the intermittently beautiful but mostly harshly lived existence of people from his adopted semi-rural community in northern New Mexico’s town of Bernalillo—where Lyon had relocated during the early 1970s. His ongoing documentation in photographs and films of the lives of Willie Jaramillo, his siblings, and other neighborhood children from the early 1970s onward is of particular note—most of these young men would suffer tragedy as adults through violence, death, or systemic incarceration.

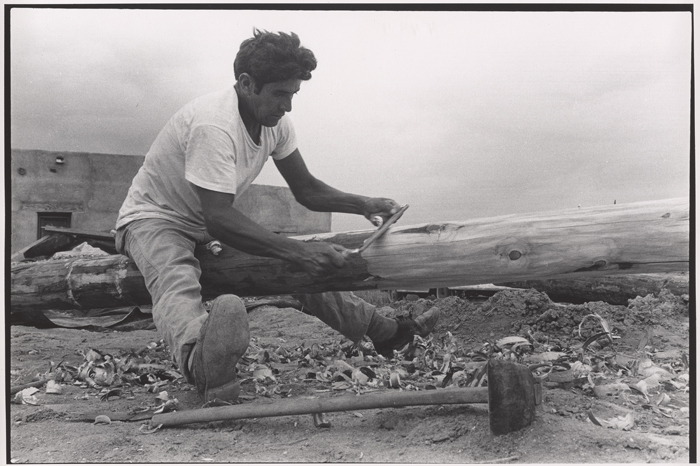

Starting in the early 1970s, Lyon and his wife Nancy would build a traditional adobe home with the assistance of Eduardo Rivera Marquez (Eddie), an undocumented laborer from Mexico. As always, those around Lyon became collaborators and co-conspirators in his poetic but straightforward films and photographs, and Eddie was no exception. By the end of the 1970s, the Lyons would leave New Mexico to raise their family in New York State but would return to Bernalillo whenever possible. They now live most of the year in New Mexico.

I first met Lyon during the mid-2000s when he gave a lecture at a Stanford University photo conference. (I have been a fan of his work since I began studying photography in the 1980s.) We connected through our shared photographic interests, offbeat sense of humor, and a mutual interest in documenting the diverse communities of the American West. We have remained friends ever since. Additionally, in 2016, I worked with Lyon to publish his essay and photographs, in a now-defunct online journal, from Burn Zone, his prescient memoir of a series of post-2000 devastating fires fueled by anthropomorphic-driven climate change that engulfed the forests and wildscapes of Northern New Mexico’s mountains over the past years.

With the exhibition launch of Journey West: Danny Lyon at the Albuquerque Museum, on view from March 11 through August 27, 2023, I spoke with Danny in late April 2023 about the exhibition.

Kim Stringfellow: You continue to bear witness to underrepresented and marginalized people, places, and events. Why is this so important for you to do so?

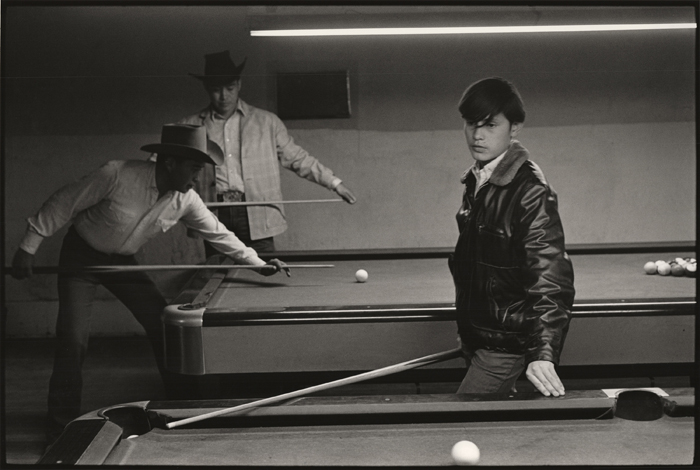

Danny Lyon: I went to the show the other day. When I got there, a guard came over and said there’s a guy who works here whose uncle is in my film, Willie. Shortly after, another young museum employee approached me, commenting, “I love this picture,” (pointing to a photo taken in a Navajo pool hall). Then he said, “I’ve never seen anything in this museum that interests me until this show. I love playing pool.”

Lyon comments, “When the guards come up and comment, ‘I love this show,’ you know you’ve done something right.”

Elaborating, Lyon states: I would like to think that in the show, in the books, and in the work that I do, I’m speaking to people about the nature of humanity—the nature of who we are and the nature of who the viewer is and how they act. In that sense, I hope to change people. That’s what I do. I don’t know whether it works—ask me in 100 years because, in the end, people do change.

Stringfellow: Looking over your immense body of work presented in Journey West, your dedication and commitment to exploring the world around you, no matter where you land, seems inexhaustible. Can you discuss this aspect of your work?

Lyon: I think the media is a very powerful platform, and you and I are part of it. We have a megaphone that the guard in the museum doesn’t have. But on the other hand, it is just a show. It is up to the people who come in there to make sense of it. But the arts can ultimately change people. Even one person can change others.

Stringfellow: In an earlier interview, you stated to your friend, the celebrated documentary photographer Susan Meiselas, that your greatest strength is empathy. Why is empathy so central in your work?

Lyon: We wear our hearts on our sleeves—this is something my father said of my mother. Like her, I have this ability to empathize with people, and I feel that you become that person—when you empathize and experience their lives emotionally. If you do that long enough and you do this professionally, then you have to raise the question, “Who are you then?” In other words, if Billy McCune is an alter ego, if Willie, Joselyn, and Jimmy Renton also are—then who am I?