Autumn Knight’s multimedia work at the Visual Arts Center connects video, vinyl drawing, lecture, and performance to challenge audiences to re-think their ideas about disappointment, doing nothing, and sounding.

A few weeks back, I drove from Houston to Austin to see the exhibition If we are here…, organized by Nicole Smythe–Johnson at the Visual Arts Center at the University of Texas at Austin. The show’s title suggests the formation of a “we” who is present in a space, in the here and now. The title’s conditional “if” leads to the implication, nay the expectation, that something else might happen once “we” are in the space. What would happen if “we” are here? Who is the “we?” The curation of three Black women artists into the show—Deborah Anzinger, Tsedaye Makonnen, and Autumn Knight—suggests that the presence of Black women artists in a space creates a situation of grammatical conditionality: if these individuals are present, then other things might occur. There might be an otherwise. And yet, the title leaves an openness about who the “we” might be, and the show seems to insist on this generative slippage.

I drove over to see the show because I knew that I wanted to see the two performance interventions that Autumn Knight was scheduled to undertake on the campus: Nothing #51: UTA on Friday, February 16, 2024, and Broad: Say Less on the following day with artist Li(sa E.) Harris. I’ve been following Knight’s work for many years, ever since we met almost twenty years ago in our hometown of Houston through an innovative community-based arts organization called Voices Breaking Boundaries. I’ve been watching Knight’s work for years, but several moments stand out: seeing her improvisational group Deep Fried in 2007, participating in her Performance Prescriptions at Diverseworks in Houston in 2011, her installation futz at Project Row Houses in 2013, and collaborating with her on a series of performances around the activity of “reading” in 2013 and 2017.

Over almost two decades, engaging with her work has enriched my own thinking about improvisation, presence, performance, groundedness, movement, and text. Her 2016 move to New York City for a residency at the Studio Museum of Harlem took her far away from the Southwest though. Throughout the pandemic, I watched her videos and performance work—Sanity TV, Nothings, artist talks, and more—and I was keen to catch her work back in Texas for the first time in a while.

These past years have brought me to new levels of anger and sadness. Despite decades in social justice organizing, “we” find ourselves witnesses to the continuing fascist takeover of Texas and the entire country and world, and watching Knight in action has always served as a balm. She does not provide an easy sense of solace though, rather a set of provocations and challenges that drive both inward and outward, arriving to critique and a sense of complicity. As Smythe-Johnson writes in the show description, Knight’s work provides a space for the spectator to sit “with our disappointment and discontent, not only as a motor of political engagement but as essentially human and valid in and of itself.”

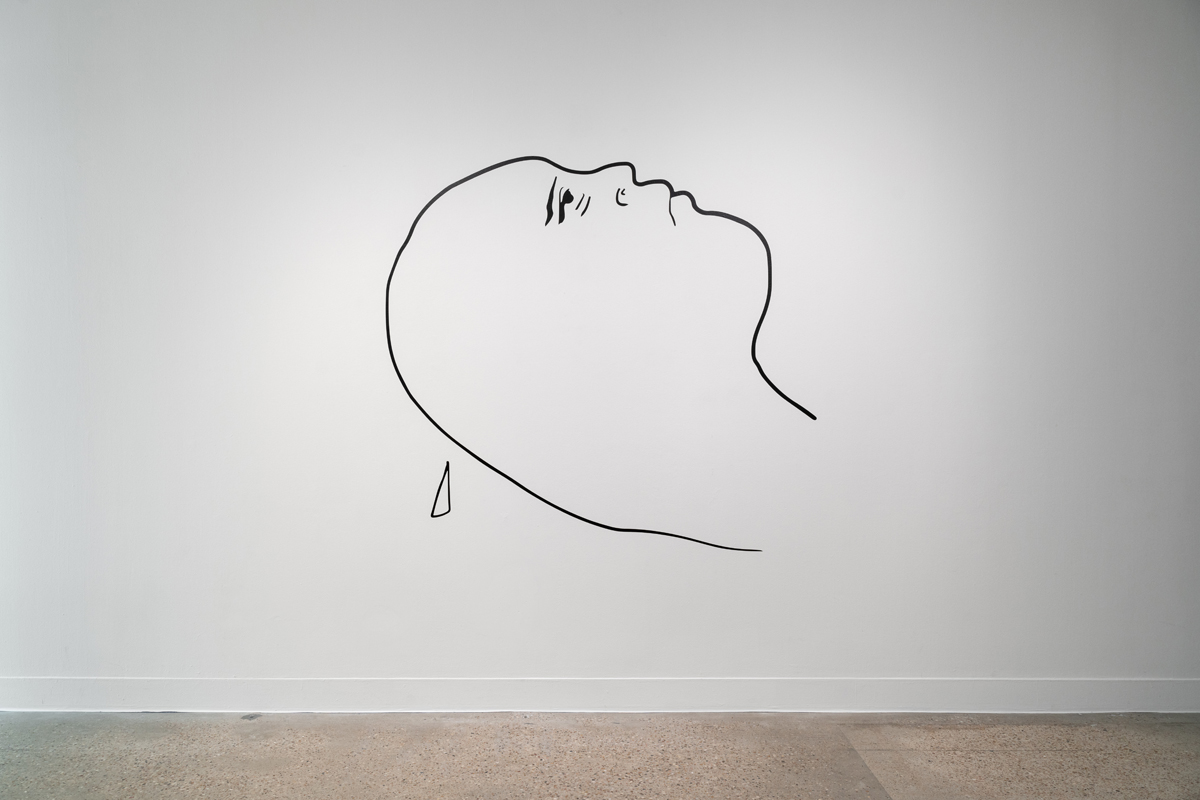

Before I took in the two performance works, I visited the exhibition in the Visual Arts Center, which features four pieces by Knight—one fifteen-minute video work entitled WV #1 Disappointment from 2020 and three vinyl drawings. The drawings are part of a newer body of two-dimensional works, many of which were shown last year in a large solo show at the Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University in New York City, which I was lucky enough to see, marveling at the two-dimensional and three-dimensional iterations of Knight’s work. The three vinyl drawings at the VAC are minimalist and gestural—a small number of black lines on the white walls of the gallery bring to life the stark outlines of three faces: one seemingly sweats a single drop from the back of their gender-unidentifiable head, another gives proverbial side eye, and the third quivers in extreme anxiety. The lines suggest faces that barely congeal on the wall, more suggestions of emotions than portraits. The outlines of these faces are haunting and strange, cartoonish in an uncanny way.

The video work that occupies one wall of the gallery begins with the voice of the late Texas Congresswoman Barbara Jordan intoning firmly, “All of us are going to suffer,” as images of a European metropolis float by from a moving vantage point in a city street flowing with cars. The video proceeds into a disquisition on the nature of disappointment, text flashing across the screen: “This is a wellness video about disappointment. / Has the subject matter alone set you up for disappointment?” Soon, numbered pithy Wellness Tips appear out of order: “#5 Manage Expectations,” “#3 Write It Down,” “#6 Listen to Black Women,” and “#1 Enjoy the Color/Colour Green.” Background shots from Paris and Venice and tranquil country scenes from the South of France, while Knight was at the Dora Maar residency, are paired with an upbeat soundtrack of songs: from the Cuban jazz orquesta music of Felix Valvert to the R&B song “Float On” by The Floaters. A twin voiceover features the artist’s voice seemingly deepened into masculine intonations in the first half, and then made higher and feminized in the second portion.

Drawing on the work of philosophers like Bill Lawson, Knight investigates disappointment—and particularly Black disappointment, the experience of a continual promise of justice while conditions of oppression and marginalization intensify. There is a sense of the perilous nature of disappointment at the end of the piece when Knight asks, “What should you take away from this wellness video on disappointment?” Then she wagers a few responses: “Hmmm… / Lean into disappointment. / Disappoint yourself everyday. / Do NOT turn disappointment into creative fuel. It is not made of the same stuff.” This is an important contradiction: the need to recognize disappointment, while keeping a certain distance from it, not allowing it to poison oneself or one’s work. As she says at another point in the video, “Be careful: one’s own disappointments can blind one to the disappointments of others.”

By the time I walked into Knight’s first performance on Friday—Nothing #51: UTA—I was excited. These numbered talks on nothingness have been a key part of Knight’s practice for the last few years. It’s a format she began in 2022 in Venice with Nothing #59, performed as part of the gathering of Black women artists and thinkers called the Loophole of Retreat. These nothings emerged while Knight was a Rome Prize Fellow at the American Academy in Rome, where she dedicated herself to a study of dolce far niente, the sweetness of doing nothing. As she has written, “I work improvisationally a lot, and that comes from a place of starting with nothing. I’m coming into space with the idea that I don’t know what’s going to happen. Nothing might happen; everything might happen. I think that’s what is so frightening to people about performance: there is a fear and discomfort to witnessing failure, but that’s the thrilling thing to me about this art form.”

In the performance of Nothing in Austin, Knight showed fifty-two slides of images—that varied from bears to puppies, performance shots, personal photos, abstractions—while reading out fifty-one statements, anecdotes, quotes, or observations, seemingly developed quite recently, with evidence of being written over the past week in residence in Austin. Knight’s nothings spanned from reflections on racialized silences in neighborhoods in Rome to flooding in Southeast Texas, from definitions of “haptic” and “embolalia” to quotes from bell hooks and Susan Sontag. She concluded with a list of jobs that she wished existed, including nothing maker, sadness alleviator, pencil therapist, and more. Between her readings of the numbered texts, Knight improvised with materials found on stage—a chair, a light, a beanie—and posed for photographs whenever she found a particularly illuminating position, often making suggestions to the photographer tasked with documenting the event. Knight is conscious about how the present event will continue to exist into the future. Because the frame of gendered and racialized expectations, projections and histories is always present, the performance begins and begins and never quite ends. It ends and it ends, and it never quite ends.

This frame of expectations and projections is also operating at an institutional level, as curator Amy Powell has written about in a book—entitled In Rehearsal—produced as part of a survey of the artist’s work at the Krannert Art Museum in Illinois in 2017. As Powell writes, “What knowledge is produced, and for whom, when a Black woman is at the center of a university art museum?” I returned to this question repeatedly over the course of the weekend in Austin.

I was left asking: what is it to respond to the state of the world currently with nothing? When does nothing become its own answer? Who gets to do nothing? And how is that nothing made to mean something by all the projections of audience members onto that nothing?

Answers to these questions are difficult to arrive at, but I have a profound sense of respect for Knight’s response to the increasing amounts of labor she has been asked to perform in arts institutions. For example, in response to the requests of historically white institutions for artist talks and explanations and contextualizations, Knight performs a very conscious series of Nothings. She turns the request to do something into its inverse, a lack, and then asks the audience to stare into it and at her, confronting their own projections all the while.

As Sandra Ruiz writes in the same volume, In Rehearsal, “[T]he only promise [Knight] offers is the refusal to harbor our sentiments. Although we imagine it’s her responsibility as a Black woman to handle and amend our hidden fantasies, Knight rejects the call to any neat and classifiable affection. She is not interested in storing our fetid feelings; instead, she returns them to us, forcing the audience/participant to be accountable to their own unconscious fantasies, regardless of how racist, sexist, and violent they may be.” This astute observation seems to get to the heart of the matter for me, and it leads me to the second performance of the weekend.

On that Saturday evening, the assembled audience was led into the black box theater for the performance Broad: Say Less—with artist, Li(sa E.) Harris. As people settled into their seats, a few chairs were left empty and Knight moved around the room, removing those that were unoccupied. The performance had begun. The artist as caretaker, room organizer, space designer, experience curator. In the performance that followed, Harris explored naming and the sounding of names of Black women, while playing the eerie and moving tones of a theremin with her arms and entire body.

Knight and Harris shared the stage for a moment as the two of them shook out sheets, beating them out, and then Knight brought out an array of implements collected on an industrial plastic table: cups, orzo, a metal serving tray, balloons, and more. What followed was an exploration of sound and embodiment, humor and amplification, ASMR-like soundings and movement. Breathing hard into microphones, rubbing balloons, splashing water, spinning the lavalier mic like a lasso. All these sounds created an atmosphere of continual tension and release, a tightening up and a letting go. At the performance’s climax, Knight grabbed a bouquet of about twenty balloons and popped each one with a pencil, tapping out a beat on one before exploding it. The tension in the room was thick.

By the end of the performance, Knight began to alternately clean up the space and to dirty it up: throwing beans all around, spraying a liquid into the air to create clouds of droplets, straightening up the implements on the table, just to pour out more beans and then cleaning the table by pushing them onto the floor. Finally, Knight grabbed an oversized purse and walked out, as did Harris at the same moment through another door.

As “we” sat in the space, I was left wondering when and whether the performance would end. Who ends something? Who gets to end it? If the artists have left, if “they” are not here anymore, and if “we” are left to make decisions. What does it mean to do nothing when “we” do not know what to do? Or what if doing nothing is what can be offered? To wait and observe and watch. To wait for the ending that does not quite arrive.