Appeals to authenticity are everywhere today. In everything from advertising to yoga classes, we are reminded to “keep it real,” to “live your best life,” and be true to our authentic selves. These directives express both a deep psychological longing to find meaning and a moral imperative to avoid presenting a false persona. Our obsession with authenticity reveals our collective anxiety in a rapidly changing and increasingly uprooted world, where one’s identity might seem defined by social media and consumer culture, where belonging is expressed in hashtags and status updates, and even news and scientific fact are suspect. As Jason Tanz described in Wired, we are living in the “age of deceit”—a “post-fact era of fake news and filter bubbles,” where truth is only invoked if it furthers an argument or sells a product.

Although authenticity is the pop culture buzzword of the moment, the meaning of authenticity has been debated for decades in historic preservation. In the last twenty-five years, the attributes preservationists use to gauge the authenticity of historic buildings and sites have broadened to include both tangible and intangible qualities. Communities nationwide are beginning to acknowledge that what is “real” and “true” in preservation is informed as much by material integrity as by cultural values, memories, and experiences of a place. However, the relationship between authenticity and imagination, as well as the uses of authenticity in community development, remain subjects that deserve further examination. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Santa Fe’s historic districts.

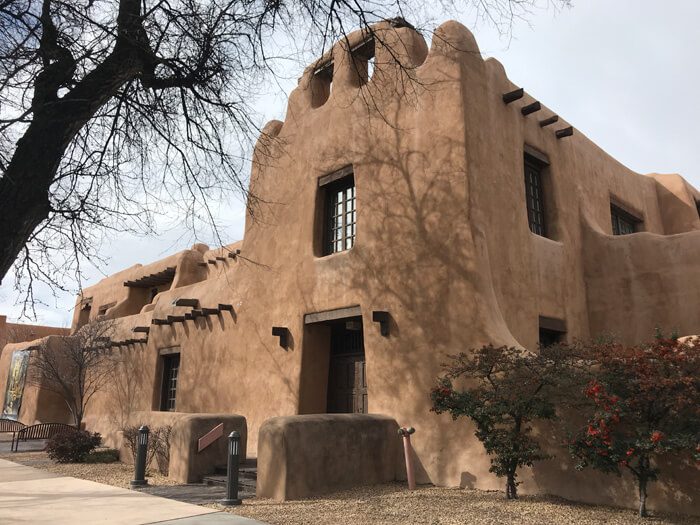

Santa Fe has been in the business of historic preservation since at least 1912, when the first city plan called for all new buildings in the downtown area to “conform exteriorally with the Santa Fe style.” The “City Different” movement that followed consciously sought to attract tourists and residents to the new state capital by promoting “Santa Fe Style” as a revivalist blend of regional architectural styles—a project that relied heavily on the romanticism and nostalgia that was so prevalent in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In The Myth of Santa Fe, author Chris Wilson notes that the removal of Territorial-period architectural details, particularly in and around the plaza, along with speculative reconstruction (for example at the Palace of the Governors in 1913), was central to the effort to create stylistic unity with the newly coined Santa Fe Style. As the City Different movement continued to gain momentum, some of our most treasured tourism-oriented monuments of Santa Fe Style were erected in the Museum of Fine Arts (now, New Mexico Museum of Art, 1916) and La Fonda on the Plaza (1919). Meanwhile, entire blocks of one-story, Mexican-era courtyard houses around the Plaza were demolished and their residents displaced.

If we can accept that ideas of authenticity are relative, informed by cultural context, community values, and personal experiences, can we not also acknowledge that some degree of imagination

is at play?

In 1957, the City of Santa Fe adopted its first historic preservation ordinance, initiating a practice of regulating and enforcing harmony of built form through a combination of preserving old structures and requiring that new construction mimic the old. As a result, Santa Fe has become one of the most celebrated tourist destinations and hottest luxury-home markets in the country. Advertising for both tourism and real estate continues to rely on romantic descriptions of the City Different—a place that entices people through exoticism and sentimentality for the past, beckoning them to imagine a simpler, nobler bygone era that never truly was.

In Santa Fe, the pursuit of authenticity that is so essential to the practice of historic preservation is also inextricable from the romantic imaginings that created Santa Fe Style and the City Different movement in the first place. As the economic, political, and development climates change, so has our use of these ideas to forge and maintain an emotional connection with place in a city that has changed dramatically over the last several decades. Santa Fe’s historic districts have seen exponential rise in real estate prices, a growing housing affordability crisis, and steady displacement of the districts’ legacy residents and businesses. In 1991, in response to the city’s recent population and tourism boom, coupled with accelerating displacement, future mayor Debbie Jaramillo remarked, “We painted our downtown brown and moved the brown people out.” Among new generations of preservationists and anti-displacement advocates alike, Santa Fe’s historic districts have been criticized as “Fanta Se” [read: “fantasy”] and “adobe Disneyland.” Such accusations call into question the commercialized claims of authenticity that are often associated with gentrification. At the same time, they also urge the preservation community to reconsider what scholar Jeremy Wells has referred to in Preservation Leadership Forum Journal as the “traditional, fabric-based definition of authenticity [which] ignores a diverse range of subjective meanings that may, in fact, be immensely important” to the larger community.

Since at least the 1990s, the role of preservation in reinvestment, revitalization, and gentrification of local historic districts and urban places nationwide has been the topic of passionate debate. Historic neighborhoods experiencing gentrification have become contested grounds where differing values are confronted, defined almost as much by what has been lost as by what has been saved. Assertions of authenticity are made to distinguish historic districts from the perceived placelessness and homogeneity of more recently developed areas. Such claims are inherently oppositional—a place is authentic because it is not fake, it is not standardized. The quality of authenticity is positioned in contrast to those things, people, places, that are not authentic. This oversimplified relationship masks shades of gray, layers of history and association, the complexity of historical trauma, and the plurality of identity. Invoking authenticity in this context is an exclusionary act, which serves to deny and dismiss aspects of community-making that are difficult to reconcile.

Authenticity in historic preservation has traditionally relied upon a clear distinction between what is “real” and what is “fake,” based on notions of empirical reality and absolute truth. But what do we make of it when this distinction isn’t clear, when age and “realness” are no longer legible in the built environment, as is so often the case in historic Santa Fe? If we can accept that ideas of authenticity are relative, informed by cultural context, community values, and personal experiences, can we not also acknowledge that some degree of imagination is at play? And what of this pervasive longing for connection to place, especially in a destination city like Santa Fe, where our commercial identity and local economy have become dependent upon branding and selling an image of ourselves that relies heavily on romanticism and nostalgia?

As we move into the future as a community and work towards addressing the complex social inequities that divide us, we are called to “get real” in facing the multifaceted truths of how we got here, what we value, and how we manage the change that is sure to come

Santa Fe’s historic districts are the result of a compelling combination of saving remnants of the actual past and reviving notions of an imagined one—a practice that is now over a century old and one that has acquired meaning in its own right, creating immense economic and symbolic value along the way. That said, as we move into the future as a community and work towards addressing the complex social inequities that divide us, we are called to “get real” in facing the multifaceted truths of how we got here, what we value, and how we manage the change that is sure to come. Perhaps we can view the importance of preservation through the universal need to orient and ground ourselves within an ever-changing story of place and community. Sociologist Sharon Zukin puts it well in her book, Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places:

“Though we think authenticity refers to a neighborhood’s innate qualities, it really expresses our own anxieties about how places change. The idea of authenticity is important because it connects our individual yearning to root ourselves in a singular time and place to a cosmic grasp of larger social forces that remake our world from many small and often invisible actions. To speak of authenticity means that we are aware of a changing technology of power that erodes one landscape of meaning and feeling and replaces it with another.”

It is time for Santa Fe to have hard conversations about what is most important to us in preserving our historic districts and, more importantly, how preservation may impact housing affordability, neighborhood stability, and a sense of belonging. It is vital in this process to acknowledge that a significant portion of our community has experienced displacement from our historic districts and may also feel excluded and disenfranchised by our particular project of preservation. Steps must be taken to heal this divide through inclusive community dialogue and storytelling, public art and history initiatives, and creativity in city planning efforts. Absolute and relative truths about Santa Fe’s history must both be part of the picture moving forward, and we must be brave enough to face the structural biases of our preservation frameworks and to restructure these with an eye toward equity.

In ancient Rome, the genius loci was a protective spirit that guarded sacred places. Spirit or, more generally, sense of place, has become synonymous with the feeling of being in a distinctive place that has been loved and cared for by its inhabitants over a long period of time. As such, Santa Fe’s genius loci is its authenticity, bringing together our love of the physical features of this place—the style of architecture, arrangement of pathways, interplay of rivers and woods and mountains—as well as its intangible aspects—our values and beliefs, personal memories, present experiences, traditions of art, story, song, and celebration. In this way, perhaps our vision of an authentic Santa Fe can acknowledge a diversity of perspectives as well as the changes that our community has undergone. Preservation’s future in Santa Fe will hinge upon the degree to which we can enhance the value of architectural stewardship by elevating the value of people—those who live here, who built this place, and who continue to create the layers of story that define the very pluralities and idiosyncracies that make this place feel real, like a place where we all belong.