As Southwest art spaces such as Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum deal with art censorship allegations, national art censorship and art law experts weigh in on the broader issue.

PHOENIX—Book bans and curriculum censorship, which continue making national headlines, aren’t the only tools for divisive rhetoric and cultural erasure. Allegations of art censorship, whether it’s removing work depicting police brutality or gender identity from public-facing exhibitions, are flourishing as well.

Several art spaces in the Southwest that have explored social, cultural, and political issues through mounted or proposed exhibitions have faced censorship allegations in recent years.

In 2020, the city of San Antonio, Texas, removed artist Xandra Ibarra’s video Spictacle II: La Tortillera addressing race and gender stereotypes from its Centro de Artes gallery. That same year, the state-run New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe pulled a zine exploring the impacts of fracking from its exhibition The Social and Sublime: Land, Place, and Art.

More recently, Mesa city manager Chris Brady addressed the city’s museum and cultural advisory board about his request to remove Shepard Fairey’s My Florist is a Dick, a print dealing with police brutality, before the artist’s solo show opened at the city-run Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum in fall 2023. During the August 23 board meeting, Brady also said that the city, a politically conservative suburb east of Phoenix with a population of more than 500,000 residents, needs to change the procedures for reviewing potentially problematic artworks before they’re exhibited.

The Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum kerfuffle has left some artists wondering if there are any national regulations or best practices that museums and galleries are required to follow when it comes to dealing with artworks some people may find offensive—and whether those policies and procedures are different for public and private art spaces.

“There isn’t a national standard on this issue,” says Scott Stulen, CEO and president of the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Stulen also serves as a trustee for the Association of Art Museum Directors. “Each community sets its own standards.”

Stulen credits the advent of social media with adding a new layer of complexity to recent arts censorship episodes. “During the controversies of the ’80s and ’90s, people came to museums and saw the artworks in context, but now artworks can be put out there without that context.”

When a dispute occurs over a specific artwork, Stulen recommends bringing the artist into the conversation. “We want to give as much deference to the artist as possible,” he explains. For pieces that might need extra context, possible strategies include adding signage or didactics and offering related programming for the public.

For artists, Stulen suggests gauging the expectations of spaces that want to show their work. “Artists should know the context and intent of the gallery or museum,” he says. Meanwhile, creative venues should remember that their reputations are built by what they do over time.

“It’s important for every exhibition space to have policies dealing with criteria for artwork to be shown, whether it’s a state art museum or a university gallery,” according to Elizabeth Larison, director of the arts and culture advocacy program at the National Coalition Against Censorship.

The coalition, which comprises nearly sixty groups working for First Amendment rights and free expression, formally opposed each of the censorship incidents noted above, which all occurred at government-run art spaces.

Possible criteria noted by Larison for evaluating proposals include cultural significance, intellectual richness, professional backgrounds of artists, and regional relevancies such as social issues or traditionally underserved groups. “Our recommendations for private and publicly funded spaces are the same,” she says.

Whether and how the First Amendment gets applied in different art spaces is more complicated, as evidenced by the steady stream of nuanced case law involving art censorship. Pulphus v. Ayers (2018) unsuccessfully challenged the removal of a high school student’s artwork from the United States Capitol after Congressional Republicans considered the painting to contain anti-police messaging.

Amy Adler, a law professor at New York University and an art law expert, addressed the overall issue during an Art Law podcast from 2018.

“Private organizations can discriminate against speech based on content all they want,” Adler explained in the podcast episode. “It’s simply the government that can’t do that, and so censorship in a legal sense is really when the government is retaliating against or somehow prohibiting speech of its citizens.”

In any event, Larison notes that policies should confirm who decides which artworks get shown. “If they have trained cultural professionals, they should trust the experience and professional decisions of those people,” she says. In most museums and galleries, the curator performs that role.

Art professionals seeking additional guidance can find several resources on the National Coalition Against Censorship website, including information on artist rights and the First Amendment, best practices for handling museum controversies, and an art censorship timeline. There’s also an online form for reporting potential incidents of art censorship.

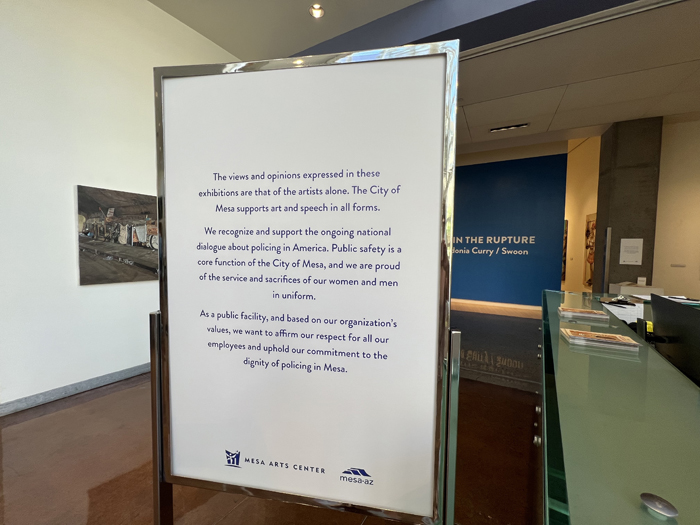

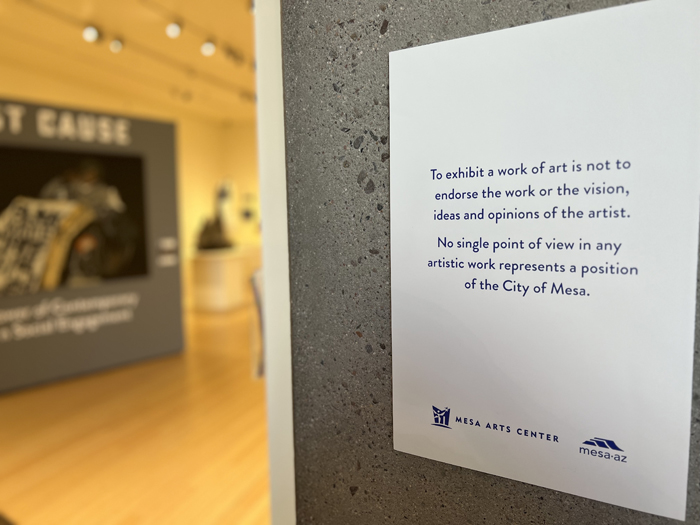

Following the censorship allegations in Mesa, two of the contemporary art museum’s five galleries remain empty, and there’s new signage at the museum. One sign says the city upholds its “commitment to the dignity of policing in Mesa.” At the entrance to Fairey’s exhibition, the museum posted another placard that partially reads: “To exhibit a work of art is not to endorse the work or the vision, ideas and opinions of the artist.”

Tiffany Fairall, chief curator for the museum, has not issued a public statement about the censorship allegations or possible changes to exhibition-related policies. Public records received by Southwest Contemporary reveal that she has reached out to Arizona museums to request copies of their code of ethics and curation policies. Meanwhile, the employment contract of Mesa city manager Brady was recently renewed with an annual salary of $350,000. The city is also continuing its search for a new director of arts and culture, a position that has been vacant since Cindy Ornstein’s June 2023 retirement.

As creative spaces continue grappling with controversial artworks, Miki Garcia, director of the Arizona State University Art Museum in Tempe and a trustee for the Association of Art Museum Directors, is taking a broader view and considering the ways museum roles have shifted over time.

“Some of the best works are provocative and thought-provoking,” reflects Garcia. “We have to remember that museums aren’t temples on a hill anymore. We’re not separate from the issues of the day.”