Phoenix-based artist Annie Lopez’s brilliant blue dress forms—tailored from cyanotypes on tamale paper—embody personal, familial, and cultural histories.

Approaching the small home that Annie Lopez shares with her husband and fellow artist Jeff Falk, the couple’s aesthetic is apparent in potted plants placed beneath a string of colorful papel picado, a small altar built next to the lime green bench on their front porch, and the skeletal form clad in a cat-themed t-shirt that sits in a large tree.

Once inside, it’s evident that Lopez’s art practice isn’t confined to the room she dubs her studio, which is brimming with books, photographs, art materials, sewing patterns and supplies, exhibition artifacts, and Halloween décor.

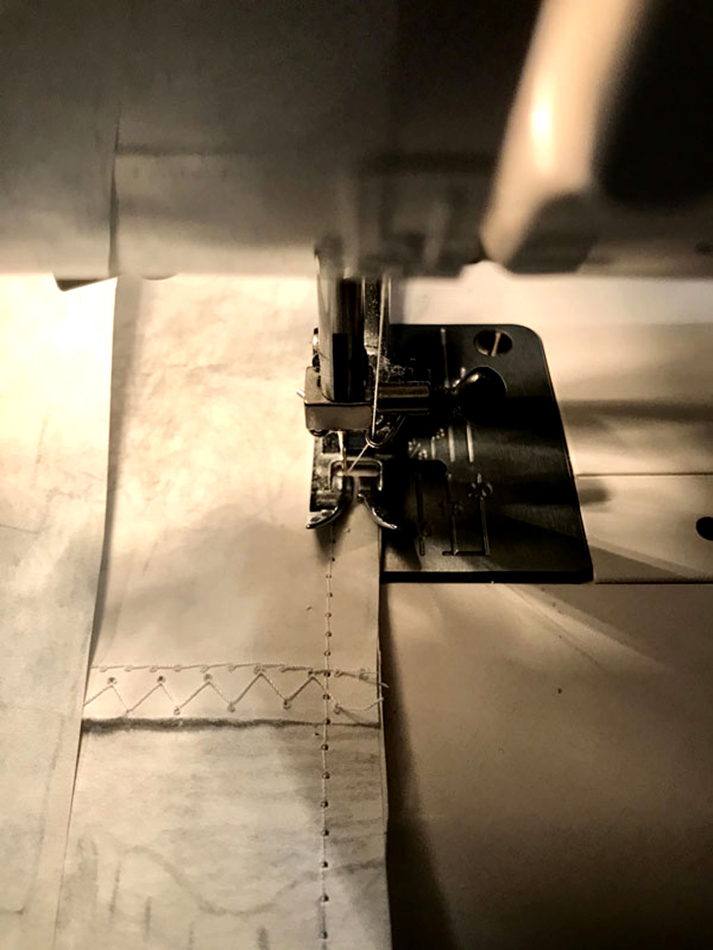

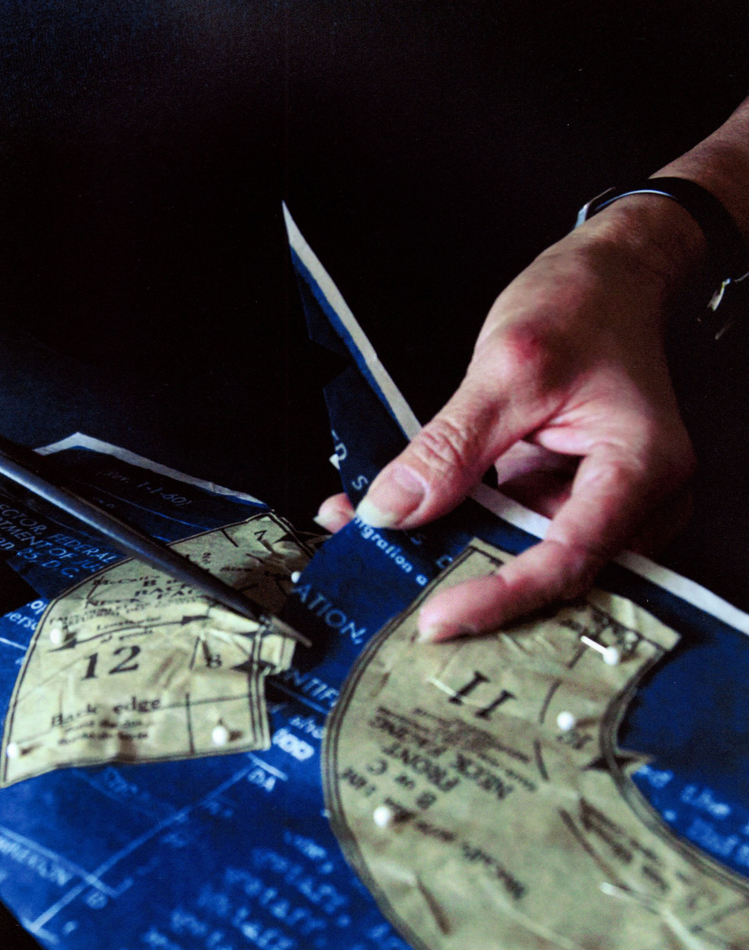

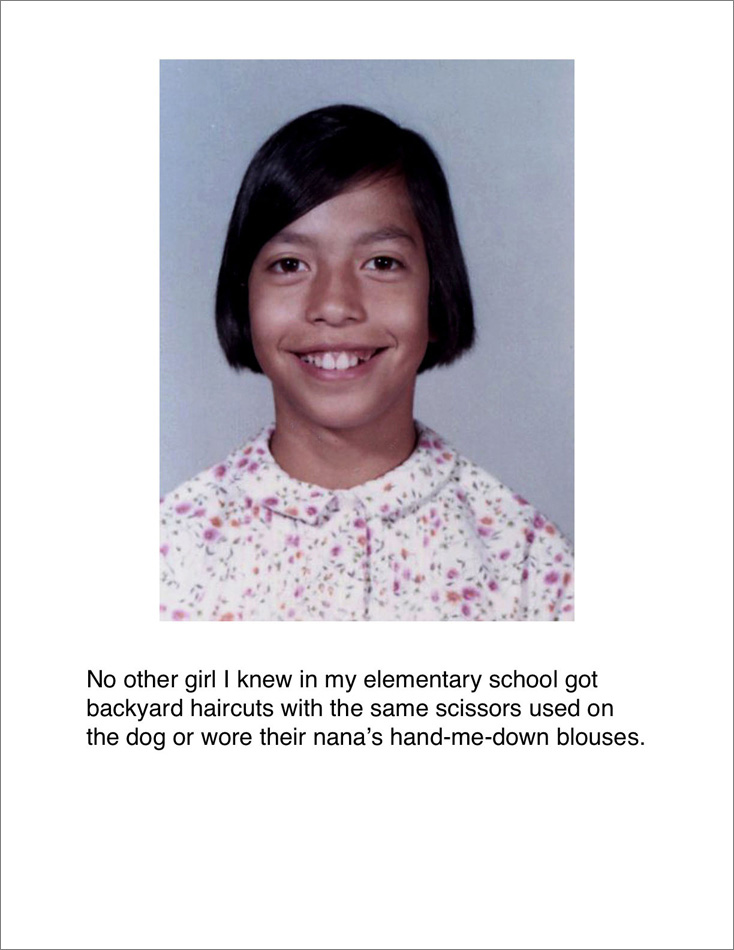

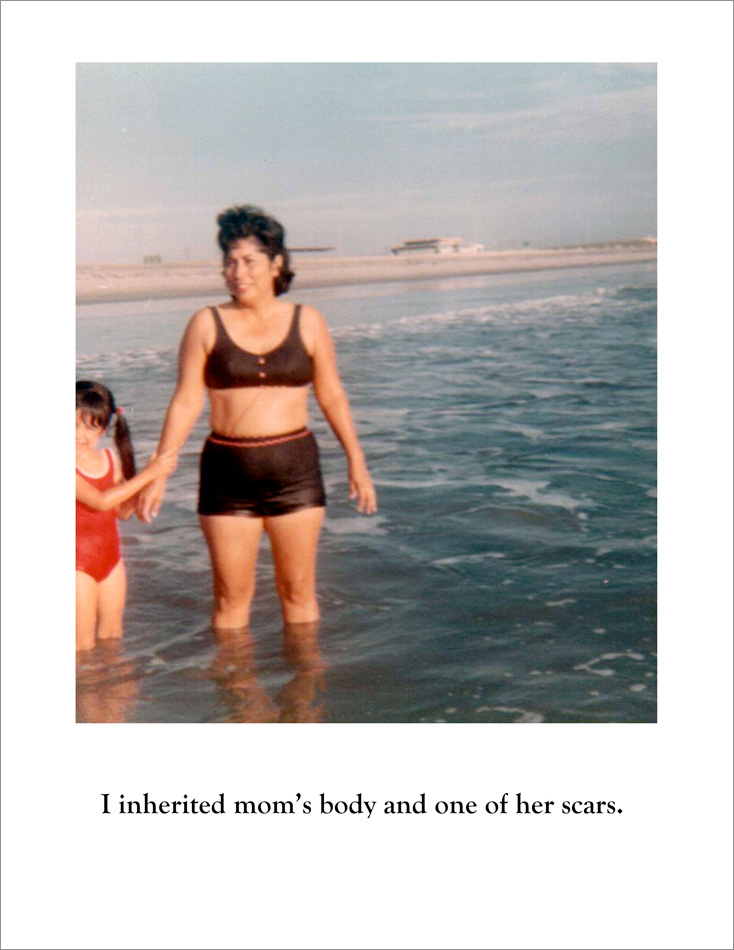

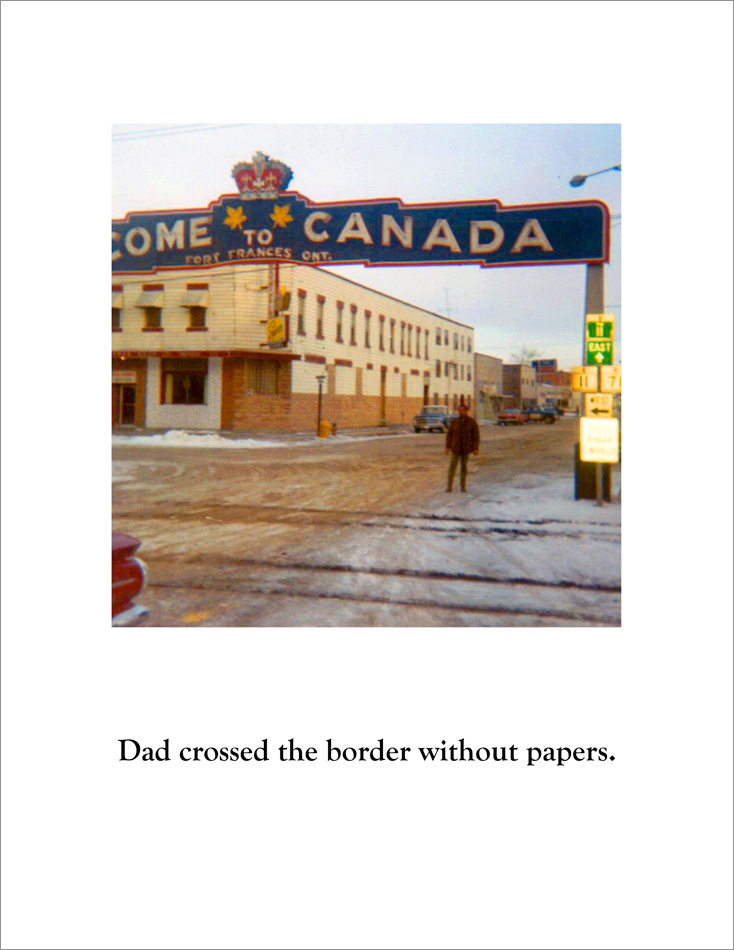

In reality, the fourth-generation Phoenician uses the whole house as her creative space, often sewing on the dining room table or using the backyard and bathtub to develop cyanotype prints using materials that hold personal meaning, such as her grandparents’ naturalization paperwork, family photos, souvenirs of childhood outings, and more. “I always want my work to connect to my story in some way, instead of just making a pretty picture,” she explains.

People don’t know their history, but I’m throwing Arizona history in their face. My family is Arizona history.

Lopez has been part of the city’s evolving arts landscape for more than forty years, initially as a member of Movimiento Artístico del Rio Salado, an artist collective founded in 1978 to highlight and exhibit the work of Chicano and Indigenous artists. Although the MARS gallery shuttered in 2002, many of its members are still staples of the region’s arts scene.

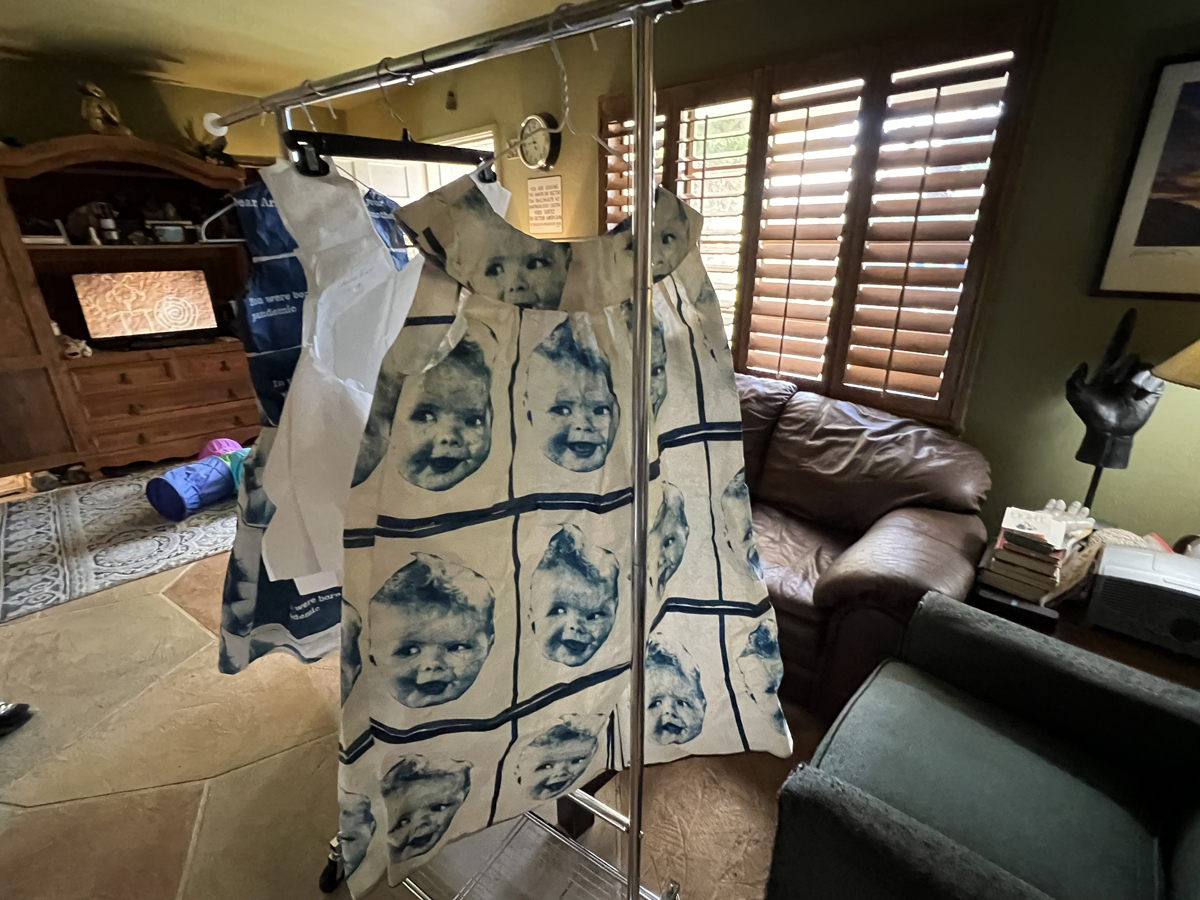

In addition to wall works, where she often pairs imagery with text illuminating experiences of racism, erasure, and marginalization, Lopez creates three-dimensional clothing forms by sewing together prints made with tamale paper, a material chosen for its ties to her Mexican American heritage as well as its strength and availability. “I knew it was a durable paper,” Lopez says, “because it holds the grease that’s in (a tamale).”

Sometimes her work skewers the art world, as with the series The Almost Real History of Art in Phoenix (La Casi Verdadera Historia del Arte en Phoenix). Often, her pieces are infused with satire. “People don’t know their history, but I’m throwing Arizona history in their face. My family is Arizona history,” she says.

Several garment bags filled with clothing forms, typically sewn using patterns sourced from thrift stores or yard sales, hang inside Lopez’s studio. Outside the studio door, she’s positioned a garment rack that holds a rotating selection of her dress forms, each sewn with a vintage pattern that connects in some way to the themes of the piece.

She’s been making the sculptural dresses since 2012, when a curator at the Phoenix Art Museum asked what she’d like to do for a solo exhibition. “I want to sew my worries into a dress,” Lopez recalls saying at the time. Ultimately, the show included numerous dresses with themes such as her father’s Alzheimer’s disease and an arson-caused fire that destroyed the family business.

Three of Lopez’s dresses are part of the Annie Lopez: Origin Story exhibition that opened at the University of Arizona Museum of Art in Tucson on January 13, 2024, and continues through June 8. The exhibition also includes numerous photographs from her Storybook series, which draws from personal memories and family experiences.

Lopez recounts crying the first time she saw the large-scale introductory text panel hanging inside the gallery that houses the show. “Okay, I’m a real artist,” she recalls thinking at the time. “Saying that I’m an artist seems so strange because I don’t think of myself that way.” In part it’s a reflection of the imposter syndrome Lopez says she continues to live with today, after being repeatedly told for so many years that she was only chosen for a particular exhibition, grant, or award as a “token.”

Recently, Lopez has been creating new pieces for something she’s tentatively calling a “grief series,” which focuses on the loss of family members including an older sister and the couple’s firstborn child. Meanwhile, she’s continuing to record everyday observations and reflections in notebooks or on her cell phone so she can cull them for her future forays in visual storytelling.

Moving forward, Lopez hopes to collaborate more with other artists and further exhibit her photographs. “I’d love to have a whole show of photography,” she says.

Whatever she’s making, it’ll likely take shape in the home that doubles as a studio for both Lopez and Falk, where a trio of black and white cats roam amid their eclectic assortment of furniture, found objects, and art supplies—and the front porch altar bearing remembrances of family and fellow artists channels the creative ethos at the heart of it all.