Movimiento Artistico del Rio Salado, or MARS, a Phoenix-based artist collective, became an inclusive home for Chicano and Indigenous artists starting in the 1970s.

The jury is out on who named Movimiento Artistico del Rio Salado, the Phoenix-based Chicano artist collective known mostly by its acronym: MARS.

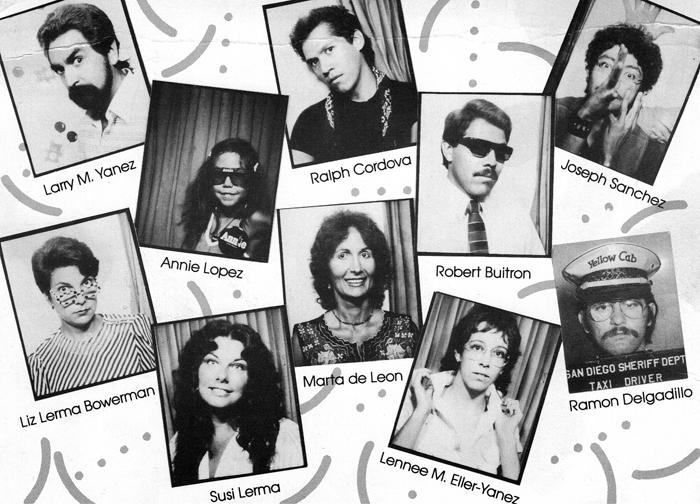

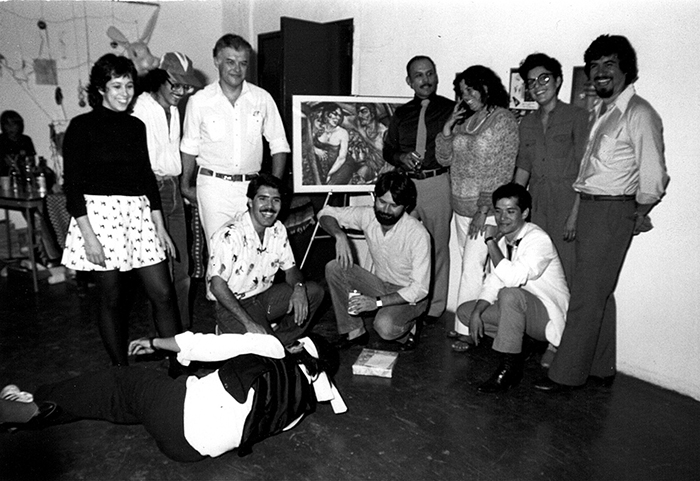

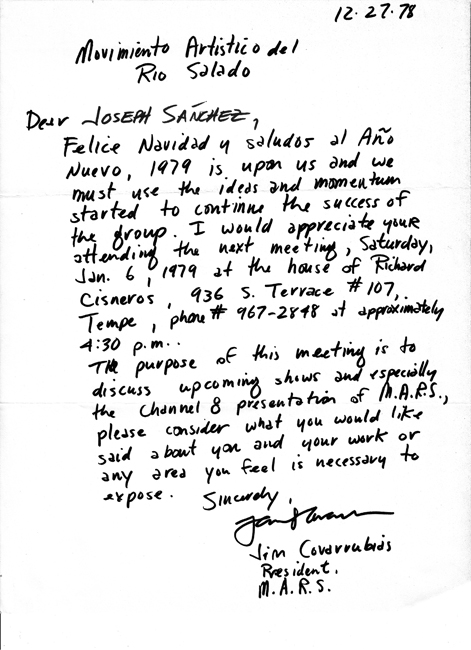

“I thought I came up with that name,” Jim Covarrubias says of the organization he co-founded. But he’s heard the Chicano artist Zarco Guerrero claim to have named the group, launched in 1978.

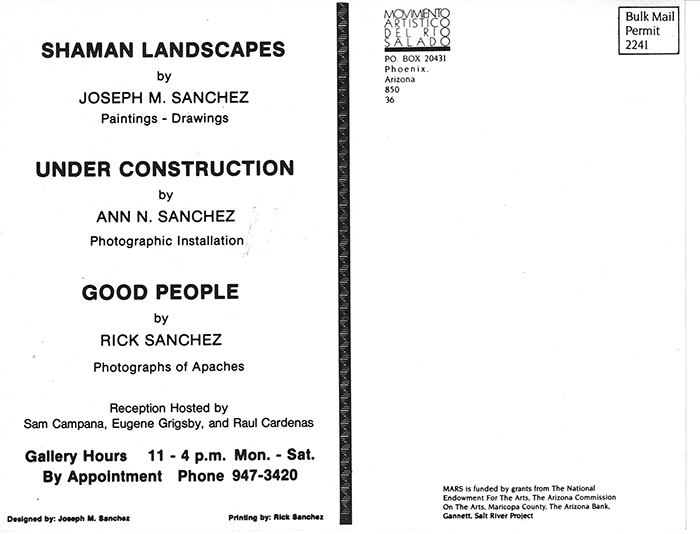

“And then one time I went to hear Joseph Sanchez speak about his art,” Covarrubias says with a laugh, “and he told the audience that he named MARS. Anyway, somebody named it.”

Covarrubias clearly recalls trying to find other Indigenous and Chicano artists in local galleries in the late 1970s, when he was a young man studying art at ASU.

“There were no Latino artists, no Native American artists in any gallery here,” says the renowned painter. “So I finally thought, I’ll get the guys together, and we’ll do a show.”

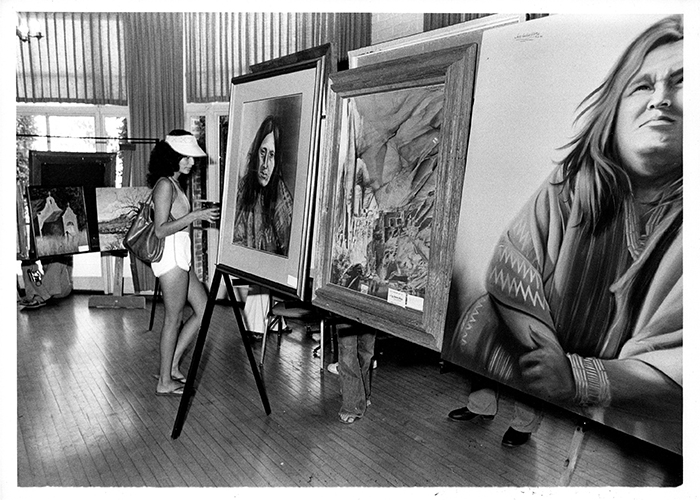

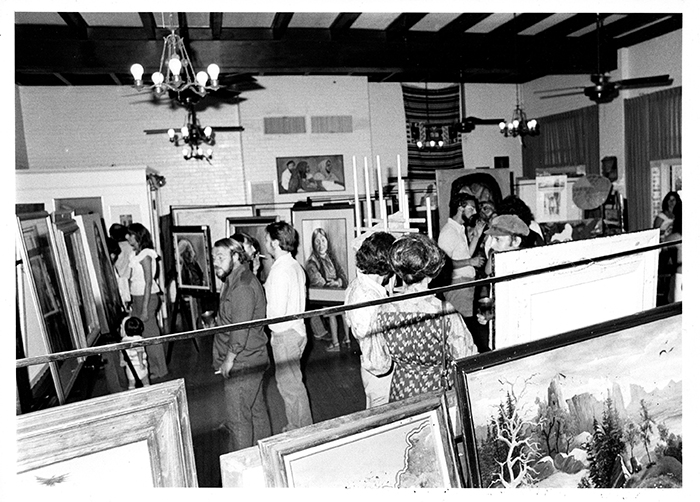

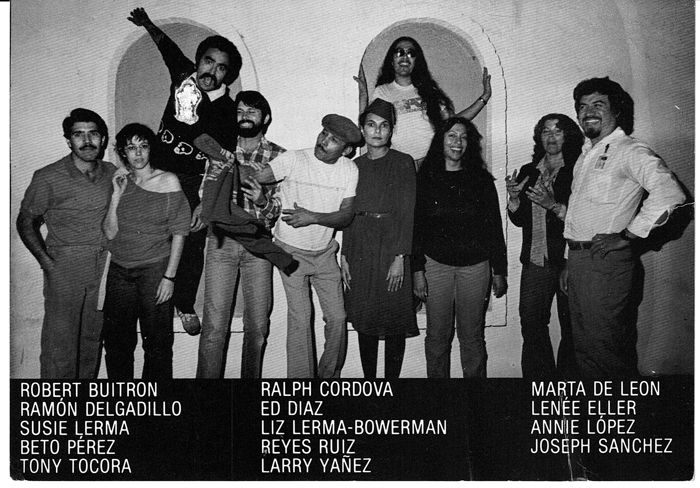

In addition to Covarrubias, those “guys” included Sanchez and Guerrero as well as Manuel Acuna, Andres Giron, and Robert Borboa, among others. Their initial exhibition was billed as the First Annual Arizona Chicano Art Show and took place at Encanto Park’s Pavilion Room. Its preview audience was small—at first.

“There was a band playing at the Encanto bandshell,” Covarrubias remembers. “I got on their mic and told the audience, ‘We’ve got an art exhibit next door.’ And there was silence. So then I said, ‘We have free beer.’ They stormed the place.”

The next day, the artists returned to collect their artwork. “We started talking about doing the exhibit again,” Covarrubias recalls. “And about making it into something bigger.”

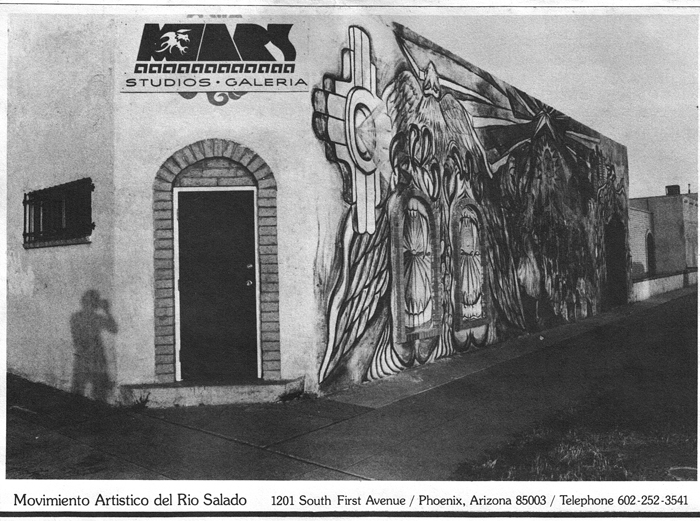

MARS was born. Depending on whom you ask, its first gallery space was either an abandoned Chinese market or an empty storage unit full of old school supplies. Everyone agrees that it was located at Yavapai Street and First Avenue and donated by the local health and human services facility Valle del Sol.

“We were there for about eight years before we moved to the Luhrs Building,” former MARS member Robert Buitron says. “By then MARS had really caught on.”

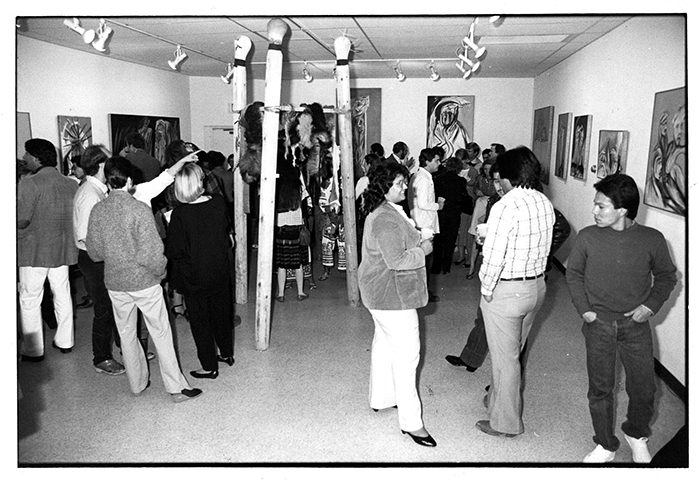

Its gallery shows drew crowds, and its audience grew. Cesar Chavez turned up at one exhibition; mayor Terry Goddard at another. Artist Ed Mell was a MARS fan, as was artist and Arizona historian Bob Boze Bell. Senator Dennis DeConcini talked up the organization to his constituents.

At first, its membership was primarily Chicano and Native American artists who wanted to show in a gallery where censorship wasn’t an option and commercialism wasn’t a concern.

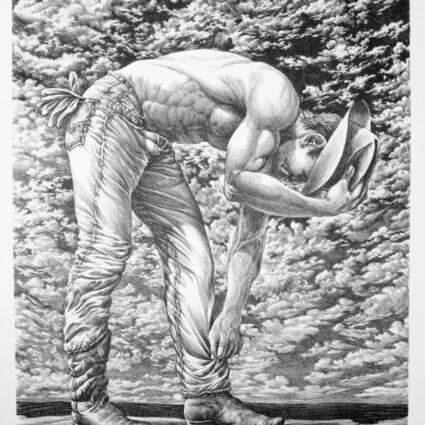

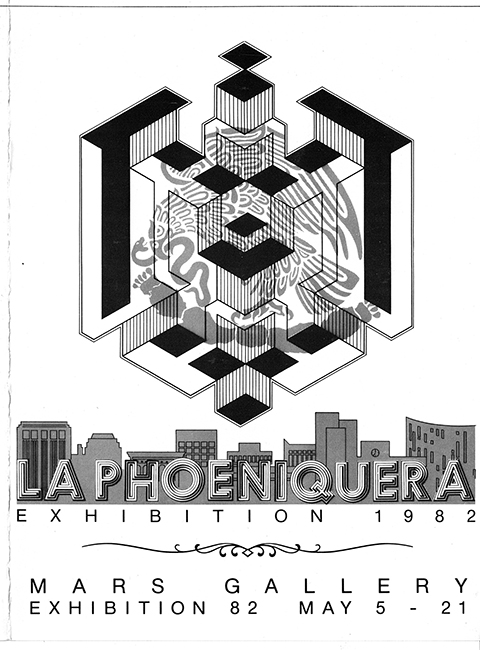

MARS quickly gained a reputation for unusual and consistently excellent exhibitions. Its La Phoeniquera shows illustrated Chicano life in Phoenix, and its solo shows—José Giron’s watercolor portraits of Aztec musicians and mariachis; Guerrero’s series of face masks of local politicians; conceptual art by the late Ralph Cordova, a founder of MARS—were revelatory and new. MARS wasn’t above controversy; Jeff Falk’s “Dead Elvis” performance pieces and Cactus Jack’s Piss Helms (depicting Senator Jesse Helms floating in a jar of urine) got a lot of press. While the Phoenix Art Museum wouldn’t think of displaying work by MARS artists, the group’s shows routinely traveled to galleries and museums around the country.

“We needed MARS,” the artist Annie Lopez remembers, “because unless it was Cinco de Mayo, galleries had no place for Chicano art. Curators didn’t look at the artwork I made, they saw the color of my skin. One of them said to me, ‘Have you tried the Mexican museum?’ I still don’t know where that museum is located.”

Phoenix had no “Mexican museum,” but for nearly twenty-five years, it had MARS. It was an organization that benefited the community, says artist Joe Ray, who joined MARS in its second year. But it also served other creatives.

“Seeing how these artists handled themselves and their careers was eye-opening,” Ray remembers. “Chicano artists doing the professional development thing inspired me to think of art as a career.”

“In every photography class I ever took, I was told I wasn’t making art,” says Lopez, who joined MARS in 1982 after spotting a tiny newspaper ad about the group. There, she met people who saw her as a fellow artist.

“It was different than what I’d been experiencing,” Lopez says. “I didn’t want to be chosen to be in a show because someone thought, Hey, we need one of those brownies in here. I wanted to be chosen because someone thought my art was good.”

MARS members were competitive yet helpful, Lopez recalls. Artists would tell one another about grants or juried shows, and MARS directors often shared opportunities with their members.

“It’s rare to find that kind of generosity these days,” Ray says. “To be honest, it was rare then.”

Board members got crafty about raising money to keep MARS afloat. An annual end-of-the-year exhibition, the MARS Blue Light Special, featured lower-priced art sold just before the Christmas holidays.

“That was huge for us,” Borboa says. “Then we started a visiting artist program as a fundraiser. People like sculptor Luis Alfonso Jiménez would come in for a week and do a litho print, and we’d give half of the prints to the artist and sell our share.”

Perhaps MARS’s greatest legacy was its pre-PC history of inclusion.

“We didn’t tell potential members they had to be Chicano,” Ray says. “We didn’t just talk about inclusiveness, we represented it. We thought our non-brown members were making art that told about the experience of witnessing our disenfranchisement.”

“I’m not Mexican or Chicano or Latina,” says the painter Susi Lerma, the first white member of MARS. “I married into a Mexican-American family, and I was an activist, and a lot of my art reflected my travels to Mexico and its history. MARS welcomed me and what I had to say about the Mexican experience, even though it wasn’t my own.”

Not everyone was on board with letting white people join MARS. There was some grumbling when Falk became the first non-Hispanic member to be voted into the group. (Lerma got a pass, she says, because she was married to a brown person.) A few former members still grouse about the organization’s unbiased approach to inclusion.

“For me, MARS was about self-actualization and realization, which may be more impactful than inclusion in larger institutional frameworks,” says former director Rudy Guglielmo, who managed MARS in the late 1980s. “But there was no fundraising infrastructure to support the organization.”

In the early 20th century, that lack of funding and an overall sense of fatigue among its members spelled doom for the group. In 2002, Cordova locked the MARS gallery’s doors. By then, only three of its seventeen members were Hispanic.

“MARS died out because people didn’t want to run a brown arts group anymore,” Lopez says. “They didn’t want to write grants and do all the work of running a gallery.”

In 2007, MARS board member Eddie Shea slid the group’s 501(c)(3) tax status over to arts mavens Greg Esser and Ted Decker, who made it available to artists applying for grants. In 2012, the trio founded the Phoenix Institute of Contemporary Art, or phICA, a group focused on education and designed, Decker contends, to continue the work of MARS.

“We think of ourselves as a museum without a building,” he says. “We’ve shown artists from Brazil and done exhibits by Hector Fernando Garcia and Darrin Armijo-Wardle. We showcase local artists, as well.”

There’s been some resentment from the MARS crowd, Decker admits. “Some people see us as middle-aged white guys showing Chicano art and art that comments on Hispanic culture. But that’s what MARS was about: showcasing diversity in art.”

In recent years, phICA has focused on virtual exhibitions from Mexico, Portugal, and Cuba. Decker and his colleagues have found homes in several museum collections for the last of the remaining MARS prints.

“What they do isn’t MARS,” says Lopez. “They pick and choose artists instead of giving us a place to thrive. They keep asking me for my blessing, and I always say ‘no.’”

Lerma thinks the demise of MARS was inevitable.

“It was a group founded by emerging artists,” she points out. “And many of them have gone on to highly successful careers. Of course things were going to change. If you don’t change, you die.”

Buitron sometimes thinks launching high-profile careers by a handful of Chicano artists is plenty for the Movimiento to be proud of.

“It’s true that in a lot of ways, Chicano and Indigenous artists are still invisible,” he says. “And a lot of the younger Chicano artists today want to be recognized for their art and not their ethnic identity. But that doesn’t mean that we failed, or that we didn’t get some really great art out there into the world.”