Roswell artist-in-residence ann haeyoung confronts the geopolitics of emptiness in terra nullius at the Roswell Museum.

Roswell artist-in-residence ann haeyoung’s exhibition terra nullius, on view at the Roswell Museum until March 3, 2024, addresses the geopolitical forces affecting desert landscapes and all those living in presumed “deserted” places. Three multimedia installations of sculpture and video art scrutinize the persistent myth that locations like this need industry to make them useful and “civilization” to settle them. The term terra nullius in law, a Latin expression meaning “nobody’s land,” legitimizes the acquisition and settlement of environments by nations or companies for territorial and commercial gain.

The exhibition positions emptiness as an illusion associated with the desert to purposely erase land claims by existing inhabitants. When audiences experience the artworks in the exhibition—an array, the transit of Venus, and a device for crushing ore, all 2024—they encounter alternative visions of occupation and land use. The three gallery installations do this by misusing technology integral to the radio telescope, the optical telescope, and the mine. By mishandling these devices, haeyoung reveals that the “nobody’s land” intrinsic to terra nullius supports an extensive technological, scientific, and state infrastructure.

The installation titled an array consists of twenty-seven parabolic dishes with speakers broadcasting audio recordings of New Mexico wildlife and weather conditions. The artist was inspired to make this work after visiting the Very Large Array used by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in the Plains of San Agustin. These massive dishes listen to cosmic radio signals to better know the universe and, perhaps, find evidence of intelligent life amongst the stars. The artist recounts seeing the VLA from a distance, “They look small from far away, like these little creatures grazing out in this field. And they’re all turning in unison and they seem so alive. As you get closer, you realize the scale of them. They are enormous.” The NRAO’s website describes the desert location as ideal for its scientific research because the stillness and quietness caused by the surrounding mountains act like “a natural fortress of rock” keeping out urban sounds from cities hundreds of miles away.

While the VLA points its antennae upward into the sky, an array misuses these apparatuses by refocusing our attention firmly to the ground. When walking around an array, one notices that the sound of birds chirping and wind whooshing gets louder and softer depending on your position in relation to the antennae. The dynamic soundscape, where wildlife seems to constantly surround and move away from you, gives a zoomorphic feature to the dishes. It is almost like they are not actually machines but a herd of animals. The more diminutive an array effectively captures the artist’s first impression of the VLA radio telescopes as organic features of New Mexico’s desert grasslands. The artwork conveys that environments chosen for large-scale research outfits are not sterile, empty places, but rather teeming with noise and life. In doing so, an array challenges the emptiness favored by technology designed for discovery and exploration.

The short film the transit of Venus examines the point of view of an ambivalent worker – a recurring theme in the artist’s practice. But the laboring body in this six-minute video letter is not human, but an optical telescope reflecting on the purpose of its design. The tone of the running dialogue of inaudible intertitles is a mixture of excitement, sadness, and apathy. The telescope relays that it was created to view the 1769 transit of Venus for “exploration and innovation for the benefit of all mankind.” While at first excited about its part in new discoveries, it dejectedly recounts that innovation is “the mirage of the new frontier.” The data garnered from this real-life astronomical event greatly advanced maritime navigation, particularly aiding Western colonial powers on long voyages to distant lands. By providing the optical telescope with a human voice, the film allows the technology to misuse itself by contemplating its complicity in potential colonial applications of terra nullius.

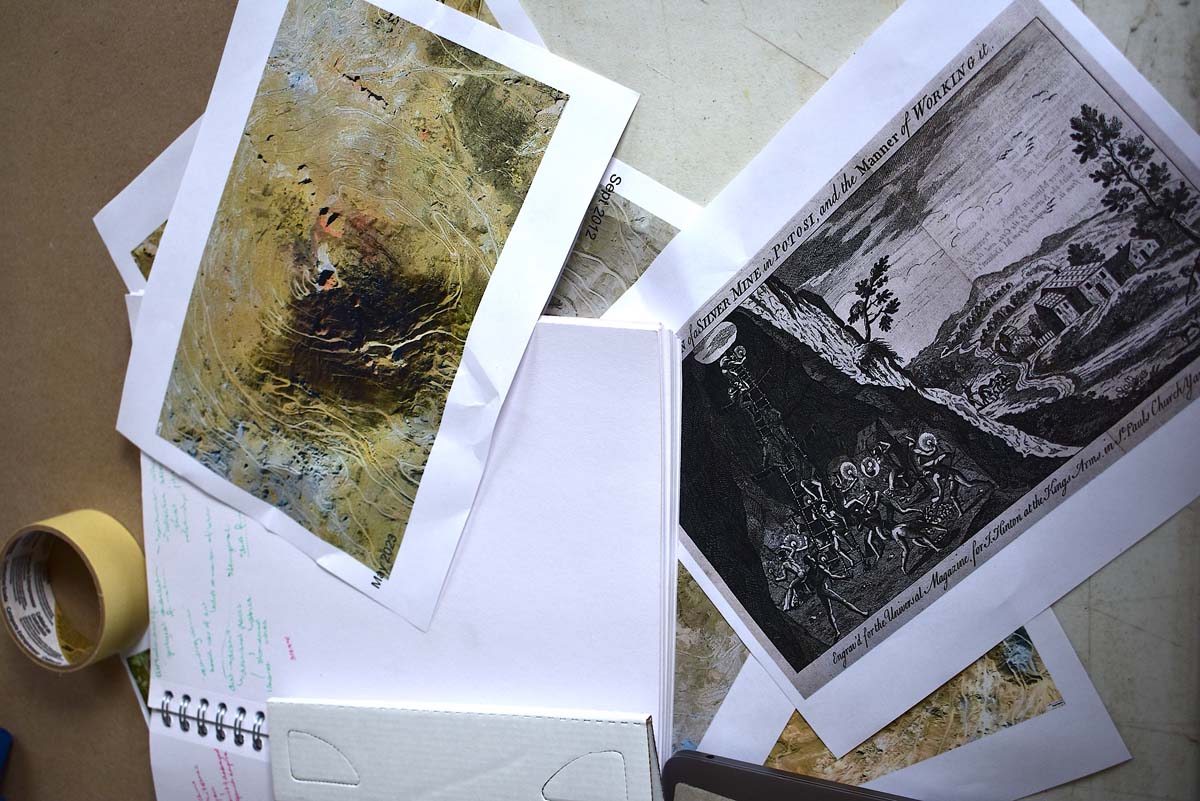

Technology that functions as an extension of the human body is pointedly addressed by the multimedia sculpture titled a device for crushing ore. The device models its design after an early mining tool for pulverizing ore called an arrastra. Devices like arrastras were used by mining industries to make deserts “productive” for white settlers occupying Indigenous lands. Taking land claims away from existing populations required the rhetoric of emptiness in terra nullius to access and control natural resources.

While machinic in function, a device for crushing ore uncannily melds the organic with the inorganic. The “arm” of the grinding mechanism recalls the sinewy quality of desiccated human or animal bone. A large rock is tethered to a knot of synthetic hair that awkwardly moves the stone around in a circle when the machine is active. These visceral properties together reference the unstable and unregulated boom-and-bust mining economies that exploit human and animal labor in so-called “deserted” places. The device turns on for five minutes every hour but has since been disabled due to the amount of dust accumulating in the gallery and dispersing throughout the Roswell Museum. The artist really enjoyed the unintentional disturbance of the sculpture, especially the idea that the device was misbehaving by creating dust that clung to visitors, surfaces, and other artworks. Making such an environmental impact after running for only five minutes every hour puts into perspective the long-term ecological impact of extraction industries.

In the 1907 book Creative Evolution, the French philosopher Henri Bergson explains that “the concept of emptiness is… nothing else but a comparison of what is there with what could be there, in other words, a comparison of the full with the full.” In their exhibition terra nullius, haeyoung proves this sentiment by uncovering the systemic invisibility of technology, bodies, and labor undergirding the emptiness and unproductivity promoted by the American military-industrial complex and histories of settler colonialism. The artist’s installations show how empty spaces are never deserted but full of life, value, and meaning for many human and non-human entities living and working in them.