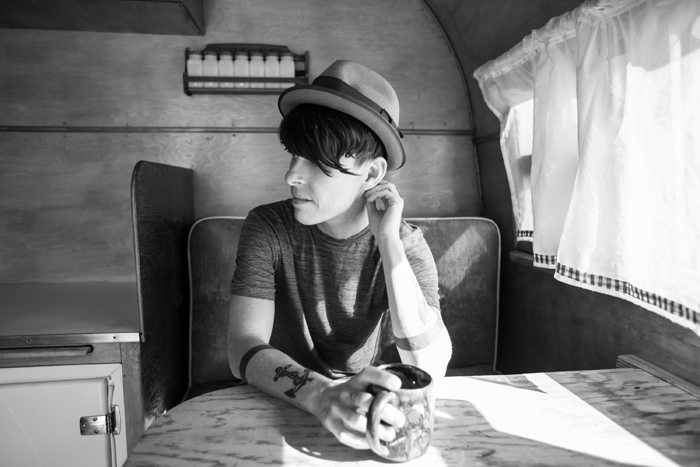

Celebrated Boulder-based performer Andrea Gibson, known for their spoken word poetry on topics ranging from gun reform to mental health, succeeds Bobby LeFebre as the tenth poet laureate of Colorado.

“I think that our natural state is astonishment,” says Andrea Gibson. “I don’t think we were ever supposed to grow out of our awe.”

Gibson (they/them/theirs) has been in awe of spoken word poetry since 1999, when they first publicly read a poem at the now-defunct Penny Lane coffee house in Boulder, Colorado. The next weekend, Gibson rode a bus to Denver’s Mercury Cafe for a slam competition, where they met “the heart” of their community.

Now after two decades of touring, the Boulder-based writer and performer is ready to serve the communities that taught them “how to be a poet,” and to help Coloradans relocate their wonderment, as Colorado’s next poet laureate.

Gibson has tended a full-time writing practice since 2005, covering topics like illness, LGBTQIA+ experiences, climate change, guns, and mental health. They have authored six full-length poetry collections and a nonfiction book, produced six albums, and been named a three-time Goodreads Choice Award finalist. Gibson is also a four-time Denver Grand Slam champion, the first winner of the Women’s World Poetry Slam, and a two-time winner of the Independent Publishers Award.

Crowning—and celebrating—these achievements is Gibson’s recent appointment as Colorado’s tenth poet laureate. Governor Jared Polis, joined by Colorado Creative Industries and the Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade with Colorado Humanities, announced on September 6, 2023, at Boulder’s Colorado Chautauqua that Gibson would succeed Bobby LeFebre in the role and serve two years.

Colorado was among the first states to institute a poet laureate by appointing Alice Polk Hill in 1919. Though tenure has fluctuated1, the multi-year appointment recognizes distinguished Colorado poets, aims to cultivate literacy and a widespread appreciation for the craft, and provides laureates with an annual $10,000 honoraria and travel stipend.2

Application is “simple,” according to finalist Meca’Ayo Coleman, and consists of a Submittable form through which aspirants nominate themselves, list references and publications, and share statements of intent. Nominees are evaluated on artistic excellence, community service, and effective presentation, and the governor chooses the appointee from four writers recommended by the CCI and Colorado Humanities committee. Joining Coleman as a finalist this year were Dominique Christina and Franklin Cruz.

Among readings, workshops, and self-directed projects3, laureates also prepare an annual program impact and success report for the governor. Gibson initially contemplated a tenure strategy but has thus far simply welcomed requests. “In the first week [after the announcement] we had fifty-five speaking invites,” Gibson says with a grin. “So right now… other people are telling me what I’m going to do.”

Gibson believes that young people invested in the spoken word genre (poetry written for performance) have partially influenced this excitement. Indeed, Gibson’s social media following is largely a younger demographic, and Gibson jokes that they are “the oldest person in this art form.” But more materially: Coloradans hunger for kinship. “People are… craving art and craving the kind of art that connects us, that builds bridges, which spoken word poetry does,” Gibson explains.

That’s what LeFebre—Colorado’s youngest poet laureate and first laureate of color—embodied during his tenure (2019-23) and sees as the craft’s higher calling. “The poet, when effective, is not merely a writer of words, but a cultural worker—a healer who uses the alchemy of language to mend the broken and bind the wounds of our collective spirit,” LeFebre wrote in a September 6 Facebook post.

Gibson learned about this cultural work—”the intersection of art and activism”—from other writers in the state. “That’s what Colorado poets taught me,” Gibson articulates. “That being a poet is less about how we show up to the page and more about how we show up to the world.”

And Gibson keeps showing up. They are vocal about gender and sexuality—even popularizing the phrase “my pronouns haven’t even been invented yet”—and note that their queer community is particularly excited to see them as Colorado’s first non-binary poet laureate, a significance not lost on Gibson. “If I were young, it would have meant so much to my own becoming to have seen someone like me in a position like this,” they say.

Authenticity also encompasses Gibson’s ovarian cancer diagnosis, a recent tectonic shift that prompted them to consider their mortality and even how to accept the laureate appointment. “I’ve been talking about [my diagnosis] not because I want people to know that I am not going to live forever, but because I want people to know that they aren’t,” Gibson explains.

But holding events virtually or outdoors and lacking certainty that they will live through their term (certainty everyone lacks) are secondary to illuminating awe and illustrating poetry’s ability to “imagine the world that is possible.”

Cancer treatment has demonstrated our collective bonds, and in Gibson’s recent work the poet endeavors to find where “people who think they have nothing in common—where their values and beliefs and joy and grief intersect.” Bridging divides, then, is Gibson’s hope for their term, reflected in Governor Polis’s statement at Colorado Chautauqua on September 6: “To be able to use poetry to bring people together is more important than ever before, and that’s my biggest hope for Andrea’s tenure as poet laureate.”

It’s the enduring message of Gibson’s work and of art’s ability to—in the poet’s experience—“nurture and heal.” But it is simultaneously the simplest and most challenging of instructions: “Truce is a word made of velvet,” Gibson writes in “An Insider’s Guide on How to Be Sick.” “Wear it everywhere you go.”