For arts communities in southern Colorado, a diminished presence of alternative newspapers like the Colorado Springs Indy means less coverage and support.

This article is part of our Medium + Support series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 8.

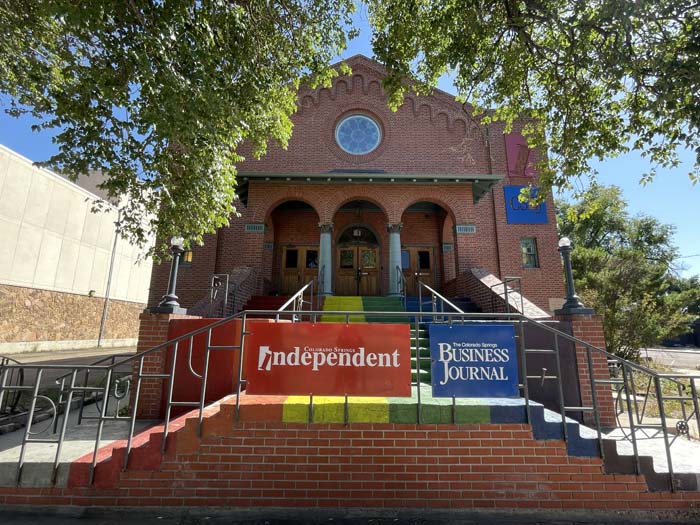

COLORADO SPRINGS—As Colorado Springs Independent editor Bryan Grossman recounts the financial woes that could sink the thirty-year-old alternative newspaper in Colorado Springs, an email from a local dance company flashes across his screen.

“We’re happy you are still the voice of our community,” the email says.

In March, the paper—which locals have dubbed the Indy—laid off its photographer, cartoonist, critics, columnists, and all but one reporter, according to reporting from Rocky Mountain PBS. A week later, Grossman made the call to publish the weekly edition with blank pages, signaling to readers what was at stake as the newspaper’s leadership scrambled to find a way to repay debts uncovered when new owners transitioned to a nonprofit model and keep the three-decade-old newspaper in business.

“By ‘community,’ I assume they mean the arts community,” Grossman says of the email, which was seeking a post in the publication’s weekly events calendar.

The death of newspapers, particularly alternative news sources more heavily focused on arts and culture reporting than traditional dailies, isn’t a new story, but it’s one that extends from the world of journalism and news-beat reporting into arts communities across the nation.

When the PULP, a monthly arts and culture newsmagazine in southern Colorado where I served as the news editor from 2012 until 2017, shuttered mid-pandemic, it was the arts community that lost among the most. Many freelance photographers, essayists, artists, and others who regularly contributed to the publication online and in print no longer had a local avenue to publish their work.

Beyond our small downtown office, which regularly held acoustic concerts for local and traveling musicians, the region lost an ally in the arts.

“It was a local supportive win-win cycle,” explains John Rodriguez, publisher and owner of PULP, which was based in Pueblo, Colorado, a thirty-five-minute drive from the Indy’s former downtown offices. “Local advertising money would be put into more local arts coverage. That local arts coverage would be an economic driver in the community telling locals what to see and do through free coverage and advertisements. Now, local companies turn to social media and are finding smaller returns.”

In Colorado Springs, a community more widely known for its military installations, mega churches, and conservative politics than its art scene, having a voice for artists of all media is significant, Grossman says. It’s also more of a challenge than it would be in other major U.S. cities.

“What sets us apart from the alt papers in cities like San Francisco, Austin, Boston is that those are progressive cities where it’s easy to be an alt paper,” he says. “It’s easy to be in the arts community, and Colorado Springs is not that city. It’s getting there; it’s getting better. Way better than it was in the ‘90s, but it’s still got a lot of work to do.”

The Indy, established in 1993, was founded as a voice that would offset that of the conservative daily, the Colorado Springs Gazette, amid a voter-backed amendment that essentially outlawed “special rights” for gays, lesbians, and bisexuals in Colorado, Grossman says. As boycott calls from major entertainers, like Barbara Streisand, grew, Colorado was dubbed the “hate state.”

“While I think Denver and Boulder have their own problems, culturally, artists have re-accepted those cities,” he says. In 1996, the U.S Supreme Court struck down Amendment 2 in a landmark 6-3 decision.

Robert Gray, president of the Pikes Peak Arts Council, describes the arts community around Colorado Springs and the surrounding communities as tight knit and growing. Everybody supports each other. That’s partially thanks to the Indy.

“They’ve always been willing to spread the word about art galleries, events, and artists,” he says. Sometimes through sharing events and free ads, sometimes through articles. “I feel like the demographic that reads the Gazette doesn’t really care about the art scene as much as the Indy does. Maybe the Gazette could catch up [if the Indy folded], but I don’t really feel like that’s their MO.”

The road back to becoming an entertainment hub has been slower for Colorado Springs, and not without growing pains. Grossman last year challenged plans from the city to build an outdoor amphitheater as news about book bans and other politically charged issues gained traction in the community.

“Part of my criticism is that we’re going to try and get people to come here to this amphitheater and we’re moving in the wrong direction in our community,” he tells me.

The Indy, now without a physical office space and relying mostly on freelance contributors, is focused on a giving campaign that would sustain the $50,000 monthly funding needed to meet payroll and other essential costs. Grossman estimates it would take 2,500 members paying $20 per month to meet that need.

Grossman still publishes music and calendar listings each week, but the music feature has been postponed since layoffs happened, he says. For food coverage, the paper syndicates a Substack column started by the former food editor.

Beyond coverage of the arts, Gray says the Indy seems to take interest in the issues that are important to local artists in a way other news organizations don’t, and that would be a big loss to the region’s entire creative industry.

Even in the wake of the blank pages that hit the Indy’s newsstands this spring and the less in-depth coverage that’s followed, it’s hard to fathom the impact of losing a news organization until it’s too late.

“I don’t believe local municipalities are taking this crisis seriously,” Rodriguez says of struggling and disappearing alt publications. “The pandemic has shown what happens when you disrupt the arts and culture economies, that millions of dollars in tax bases are lost. Everything from marijuana, the food industry, concerts, nightlife, farmer’s markets, nonprofits depend on the alts for coverage.”