June 2 – November 10, 2019

Harwood Museum of Art, Taos

Unfinished . . . is a memorial exhibition of Alicia Stewart, a New Mexico–born artist who died at the age of eighteen of an epileptic seizure. Over thirty works, including paintings, drawings, video, sculpture, and personal notebooks, span the interiors of the Peter and Madeleine Martin Gallery at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos. It is nearly impossible in this context to separate Alicia Stewart’s work from her tragic and premature passing, but my brief moments of objective viewing revealed undeniable talent and skill; her figurative works are dynamic and beautifully executed, remarkably mature despite their maker’s age. Amid the show’s beauty and sadness, we are offered a privileged glimpse into the practice, passion, and development of a young artist. In remembering and meeting Alicia Stewart through her artwork, we are confronted with something many of us likely have forgotten—the complexity and pain of being a teenager.

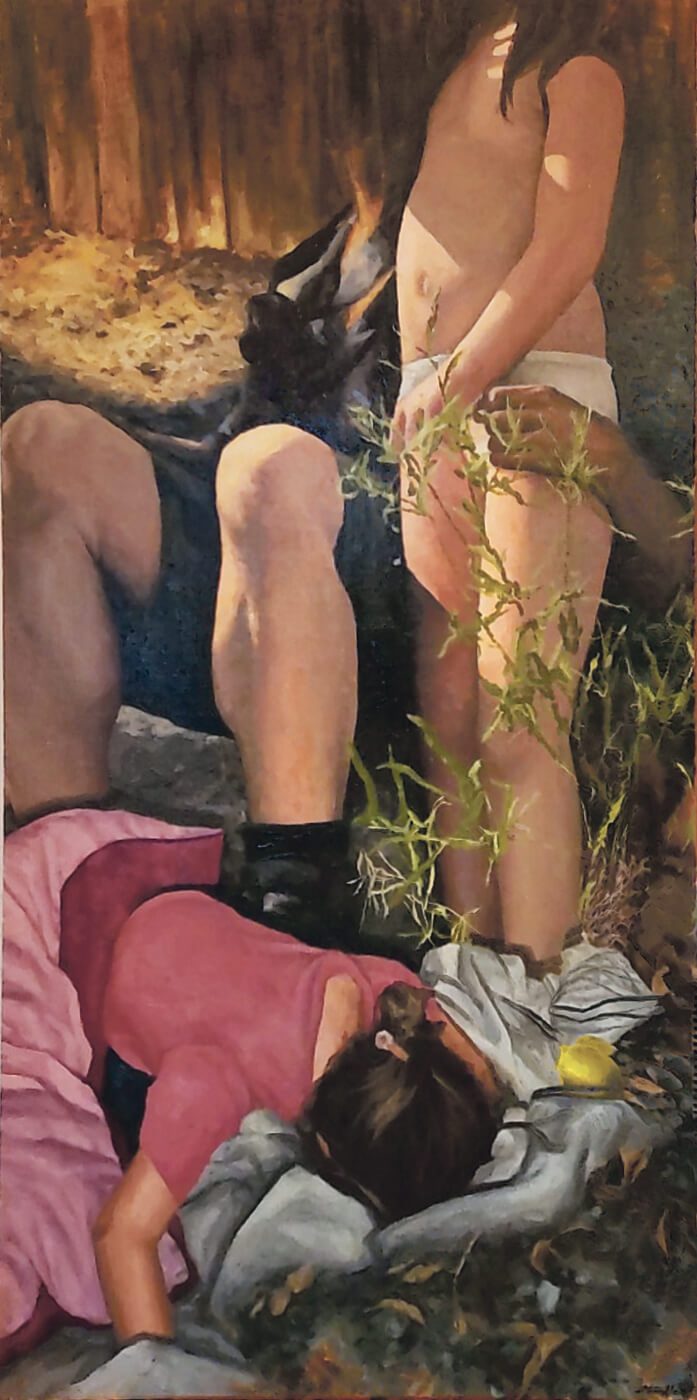

Stewart’s work is young—not naive—but beautifully young. There is a confidence and enthusiasm in her brushwork that is refreshing. Her nude figures boldly explore new parameters of a feminine world laden with deep psychological subtext. Like many young women, Stewart appears to have awareness of trauma beyond her years and bravely, and with great craft, painted it. The work in Unfinished . . . dates from 2014 through 2017, the earliest of these paintings depicting the notably clad female form. Observing the conceptual development from the painting Water (2015) to Levitation (2017), Stewart appears to have wasted no time in exploring her subject deeper, moving from self-portraits in underwear to straightforward and honest figurative nude paintings. This progression of skill and the leap into a more vulnerable presentation of the subject evidence a young woman investigating the boundary between childhood and the world of experience that lies beyond. Her skill is demonstrated and amplified by the attention given to environment; backgrounds rich in flora add an unease and vulnerability, as though the figures are being nearly subsumed by nature—or forgotten altogether. Stewart takes conceptual risks in her paintings, subtly distorting both scale and color, which points to metaphorical mechanisms at play. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the diptych Hibernation/Nest (2017), which is both beautiful and ominous, a large scale representation of Stewart honing both her technical skill, composition, and conceptual themes. Hibernation depicts the headless figure of a seated adult, presumably male, with an arm wrapped casually around the hip of a bare-chested child wearing only underwear, whose head either exists outside the frame of the canvas or is also altogether missing. A second child buries her face in a sheet at the bottom of the frame in a way that is not restful; she appears to be holding herself there, willfully refusing light or air or both. Nest depicts a reclining nude adolescent female; it’s safe to assume Stewart was the model, as she is in most of her figurative paintings. The backgrounds in both paintings are similar but different, recalling one another, most notably with the placement of three lemons between the two canvases. The reclining adolescent nude seems to exist in a memory of whatever has come to pass in Hibernation. Stewart strikes a powerful discord: the defused light, her chosen color palette, and the quality of the paint itself are calm and inviting, while the subject matter is isolating and disturbing.

Several unfinished works in the show are naturally among the most heartbreaking. Unfinished . . . is a rare capsule of work created at the intersection of talent and years of great development. There is an adolescent fearlessness in these paintings, and Stewart allows viewers to see the remarkable efforts of a young artist making use of her rapidly expanding world. Unlike most eighteen-year-olds, the perspective Stewart applied to her work made magical use of a young life evidencing wisdom beyond her years. To view this show is to acknowledge that we are missing out on the meat of what would have undoubtedly been a dynamic career. To realize the absence of Stewart’s further contribution to the field of figurative painting and that we will never see her continue to synthesize her intellect, technical skill, and love of the medium with even more emotional intelligence is to experience anew the loss of such a talent.