Windows on the Future, which spans Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and Taos, aims to re-energize commercial districts that have slowed down due to COVID-19.

In what would typically be peak tourist season in northern New Mexico, storefronts are currently either closed, empty, or seeing considerably less traffic than usual. The Santa Fe nonprofit Vital Spaces, whose mission is to utilize unused real estate for artist studios and exhibitions, had long been planning a storefront show for fall 2020, but when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, they decided to fast-track the project for the summer. “We wanted to get money out sooner to the creative community, and this format happens to be pandemic-friendly,” said Vital Spaces founder Jonathan Boyd. “It was a tool to activate all these empty storefronts, as well as be able to pay artists for their work.”

Vital Spaces worked with The Paseo Project in Taos and 516 Arts in Albuquerque to select artists and work with businesses in their respective communities. Under normal circumstances, the exhibition would be a complex one to pull off—balancing the interests of multiple non-profits and funders, dozens of artists, business owners, and community members is never easy—but in these fraught times, some of those dynamics are bound to become heightened.

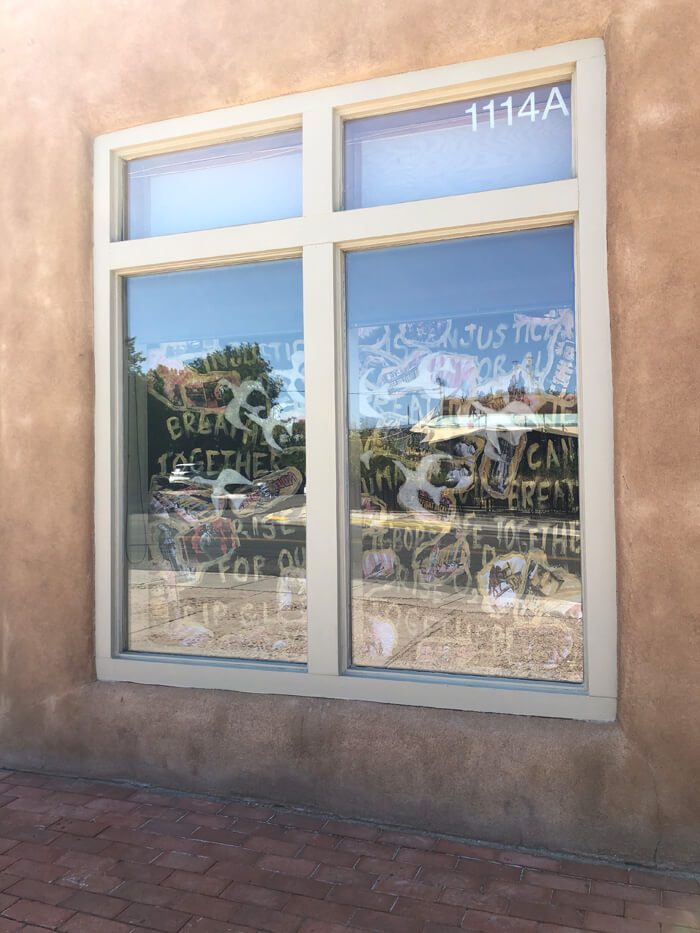

Nearly 200 artists applied to participate, and sixty were selected to install their work and receive a $500 stipend. Artists were asked to respond to the theme Windows on the Future, which Suzanne Sbarge, executive director of 516 Arts, said drew her to the project. “We are in a huge state of flux, but it’s an opportunity for change,” she said. “I’m seeing a really strong need for people to connect in other ways besides online, and I think artists are key people to look at when it comes to imagining things that aren’t here yet. Imagining the future just seems like the most basic thing we should all be doing right now.”

Hannah Yohalem, program director at Vital Spaces, said she was somewhat surprised at how optimistic most applicants’ visions of the future were. “I imagined, in the middle of this pandemic, that there would have been many more dark imaginings of the future.” The only stipulations the artists were given were no sexual imagery, no gratuitous violence, and nothing in favor of a specific political candidate due to the organization’s non-profit status. But Yohalem said she was cognizant that there would be work that the curatorial committee would find interesting and worthy that might not be a fit for every business or storefront. “Context matters, framing matters,” she said. “It could be confusing to see some dark vision of the future in your doggie daycare storefront.”

Balancing business interests with creative freedom created a number of challenges, and to varying degrees. In Albuquerque, Sbarge said 516 Arts struggled to find storefront windows that weren’t boarded up due to recent protests and pandemic closures. “A lot of windows that we would have wanted to use were boarded up,” she said. J. Matthew Thomas, executive director of The Paseo Project, said his team was “surprised at the number of vacant buildings [whose owners] just weren’t interested. I think people are more aware of how powerful the arts can be, and how the time that we’re living in is very heightened. So I think people are a little cautious.”

In Taos, two artists were asked to take down their display at the Kachina Lodge because the business owner felt their work was too political. Anaïs Rumfelt and Nina Silfverbeg created a series of crows, connected by red string “meant to represent the common thread of human life,” and owner Pender Gill felt that the work might alienate customers.

“I have complete and total respect for the artists and their work,” Gill explained to the Taos News, “but not when it jeopardizes my livelihood. This is not a gallery, it is a hotel. If I were a gallery owner and this were a gallery I would have no problem with this work. But it is not and I feel the piece represents ties to the Black Lives Matter political movement sweeping across the country.”

He also told the Taos News, “I was very happy and excited to volunteer my establishment to The Paseo Project […] I only asked that the artists’ presentation refrain from anything political, religious or dark.” Thomas said that was the only pushback The Paseo Project got from a business owner in Taos, and that he was “sad to see that politics and miscommunication got in the way of some local artists sharing their work.”

One Santa Fe artist, who wished to remain anonymous, had to take down their work because the property owner objected. The work discussed racial identity, but was not overtly political. The artist still received their stipend but chose not to reinstall their work elsewhere. “The current climate creates a culture of fear in property owners, fear to make any statement, fear to take any position,” said Boyd. “I understand that, but it’s unfortunate.”

If we are going to look to artists as guides for creative imaginings of the future, we should not expect them to make their reactions to the problems of today more palatable.

Other artists have felt more supported in making a political statement with their storefront installations. After George Floyd was murdered in late May, Vital Spaces told the artists (who had already been selected) that they were welcome to update their installations. One artist, Crystal Benson (Chimayó), adapted her installation to include text and imagery from the video of Floyd’s death. In her artist statement, Benson writes: “The whole world watched four policemen torture a helpless Black man and slowly suffocate him to death. […] If art comes from the heart and the soul, this has to affect my project.” Benson did not receive any pushback from the owner of the theater where her work is installed. “I usually do really pretty things,” she said. “But this is not a pretty time. How do I reflect our culture, and how do I reflect it in a way that improves it, or makes it known what our injustices are?”

Matt O’Reilly, vice-president of commercial real estate agency Thomas Properties, said “an art installation would have to be particularly controversial for us to object to it.” Thomas Properties is hosting five window installations in Santa Fe, and O’Reilly said he’s gotten a lot of feedback from tenants and patrons about the work. “I see a lot of benefit for the community at large,” he said. “We see it in a pragmatic way, which is we have vacant spaces, and it’s better to have something in there that allows someone to do something interesting.”

One might hope that coming out in support of justice and equality wouldn’t be seen as political or divisive—it might even attract customers, rather than drive them away. It is reasonable for business owners to want to encourage commerce and avoid conflict. But the political and social and economic are intricately intertwined, and choosing to avoid making a statement on one side or another of an issue is a strong statement in and of itself. If we are going to look to artists as guides for creative imaginings of the future, we should not expect them to make their reactions to the problems of today more palatable. As Benson said, “as an artist, you’re affected by your environment […] and right now we need to stand up for what we believe in, what we believe is right.”

Windows on the Future will continue in Taos, Santa Fe, and Albuquerque through August 2020.