Billy Schenck has made a successful career of cowboy-and-Indian pop-art imagery, but a recent exhibition of his artwork brings present-day debates over representation and authorship into the harshest of spotlights.

SALT LAKE CITY, SANTA FE, ALBUQUERQUE—In May 2022, Modern West Fine Art in Salt Lake City pulled down a virtual exhibition of artworks by Billy Schenck, who has been dubbed “the Andy Warhol of the West.”

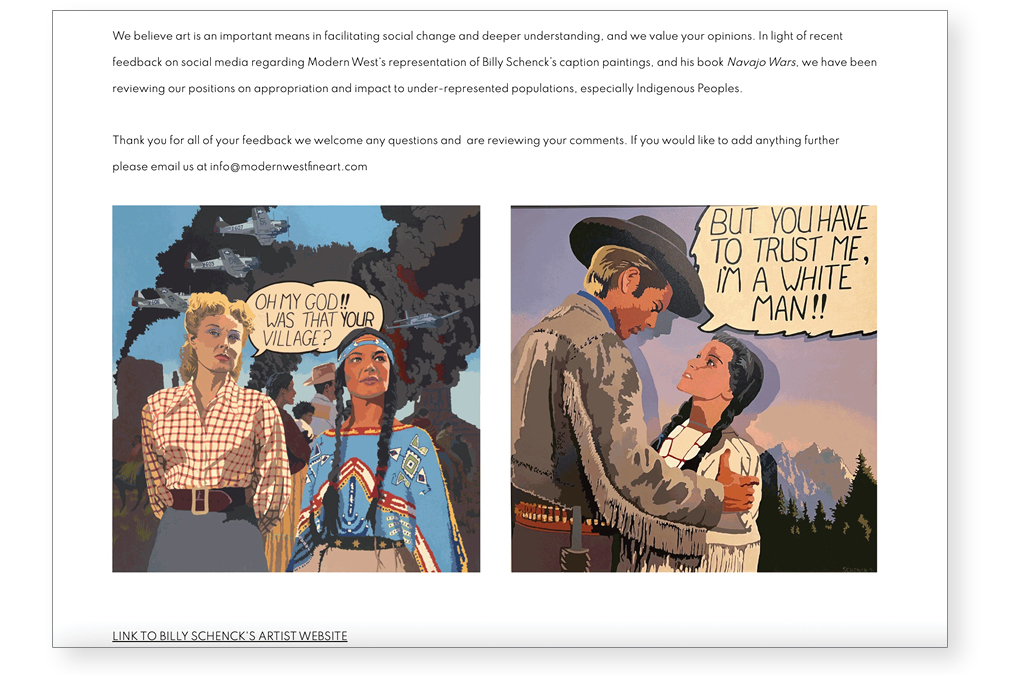

The exhibition in question, Billy Schenck: The Granddaddy of Contemporary Western Art, displayed his “caption paintings,” which superimpose caption or dialogue text reminiscent of Roy Lichtenstein over borrowed images from 1940s and ’50s Hollywood.

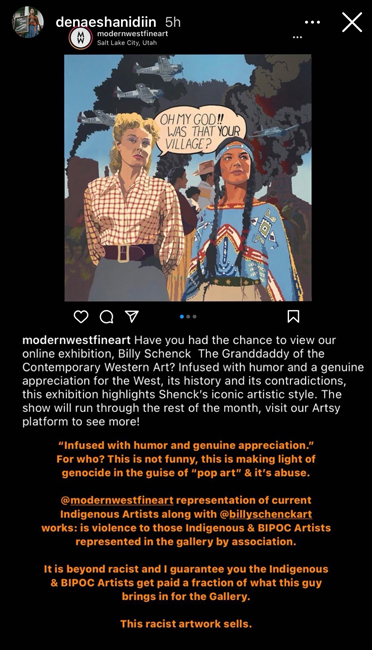

The show included Oh, My God (2021), in which a white woman and Native American woman stand side-by-side. There is war-like chaos in the background—bomber planes fly next to flame-tinged smoke that rises from dramatic rock formations resembling Monument Valley on the Arizona-Utah border.

The blonde woman, wearing a gingham shirt, stares out toward the viewer and says, in a speech balloon, “Oh my god!! Was that your village?” The Indigenous woman, wearing traditional clothing, looks silently into the distance.

Shortly after the virtual show opened, Modern West posted the work on the gallery’s Instagram profile, writing, “Infused with humor and a genuine appreciation for the West, its history, and its contradictions, this exhibition highlights Schenck’s iconic artistic style,” which has been described as ironic, nostalgic, sardonic, and tongue in cheek.

To some, this was the exact opposite of humorous and genuine.

In the following weeks and months, a series of events ignited a dispiriting chain reaction that has caused a fissure in Salt Lake City’s arts scene.

A Modern West gallery manager abruptly quit. Jorge Rojas, an accomplished interdisciplinary artist, was dropped from the gallery’s roster. The opening reception for a group show was canceled due to “security concerns.”

Modern West, which acknowledged in an Instagram post that Schenck’s exhibition was not properly vetted, paused its representation of the high-dollar artist—for approximately four months. His work is now back on the gallery’s website and walls.

When I started working for Modern West, the gallery statement spoke to creating a community-centered, inclusive, and socially conscious space. I made the decision to resign when I believed this to not be accurate or possible.

Throughout, artists and activists have publicly expressed frustration over a perceived lack of commitment to productive and sensitive dialogue by the Salt Lake City art space. Modern West founder Diane Stewart disagrees, and says the gallery made a good-faith effort to create opportunities for feedback. Others, including a Navajo Nation representative, are concerned that Schenck’s caption paintings and like-minded works by other artists fuel negative views of Indigenous people, especially Native women.

“When I started working for Modern West, the gallery statement spoke to creating a community-centered, inclusive, and socially conscious space. I made the decision to resign when I believed this to not be accurate or possible,” says Peter Hay, a former Modern West gallery manager.

Southwest Contemporary contacted a number of former and current Modern West artists. They were either unresponsive or declined comment due to fears of losing local representation by Modern West and of Stewart, a powerful figure in the Salt Lake City and statewide arts and culture ecosystem.

Schenck, who has been unnerved and woebegone by comments calling him misogynistic and a racist, tells Southwest Contemporary that his caption paintings are satirical “reverse narratives” meant to provoke thought and undo harm, not to exploit marginalized people or double-down on whitewashed histories.

“I don’t know how a left-wing person like me, who grew up on the left, could ever be identified as these horrific-sounding adjectives,” says Schenck, who says that he has supported Native American people he has worked with throughout his art career. The well-known Santa Fe, New Mexico-based artist is often considered a founder of contemporary Western Pop art. He has been displayed in worldwide museums and galleries and featured in magazines such as ARTNews, Art in America, and Cowboys and Indians.

“I don’t think that he did it in malice, and I don’t think he was being a racist,” says Santa Fe artist Stan Natchez (Tataviam), a friend of Schenck’s who has exhibited together with him. “He wasn’t intentionally trying to make people feel bad. He thought he was bringing some humor to Indian Country.”

While Schenck has been both vilified and defended—some of Schenck’s backers have alleged censorship in response to the show’s premature end—other observers are quick to point out that the artist isn’t the problem so much as a symptom of a larger issue.

Bigger-picture concerns cutting through the name-calling, finger-pointing, and rumors—no, Schenck (according to him) never sued Modern West, and no, Stewart (according to her) isn’t pulling funding from Utah’s arts organizations—revolve around appropriation and representation.

The incident has touched on ongoing considerations in contemporary art. Some ask if a white artist is “permitted” to depict people of color in a fashion that may be in poor taste, while potentially financially benefiting from the works. Others ponder: who gets to tell whose story?

Over a six-month reporting process, Southwest Contemporary conducted in-depth conversations with dozens of people—including Native activists, Utah artists, Schenck, and Stewart. To this day, members of the Utah art community remain critical of Modern West’s handling of complex questions that are in no way easy to answer.

There is, however, one item everyone seems to agree on: there haven’t been many, if any, winners in this dramatic, discouraging, and distressing ordeal.

Schenck’s online exhibition may have flown under the radar if not for Denae Shanidiin (Diné, Korean), a Salt Lake City and Navajo Nation artist, community activist, and the director of MMIWhoismissing, a mutual-aid group that brings awareness to the Missing and Murdered Indigenous persons crisis. Shanidiin, in a series of impassioned social media posts, condemned a number of Schenck’s caption paintings.

“‘Infused with humor and a genuine appreciation.’ For who? This is not funny, this is making light of genocide in the guise of ‘pop art’ and it’s abuse,” Shanidiin wrote in an April 22 Instagram story.

“The reason why this hurts so bad is because this violence is still here, and that’s where retraumatization comes in,” Shanidiin explains to Southwest Contemporary. “I think because these artworks have been in the white gaze for so long, with no Native representation and only curated and bought by white people, that it’s gone unnoticed. They don’t have the consciousness to deem these works as hurtful to a population.”

“I think it’s been a shock to a lot of folks how it’s been excused and gone on for a long time,” adds Shanidiin. “[The Modern West situation] is not an isolated issue. It happens everywhere.”

Diane Stewart established Modern West in 2014 at its original location on 200 South near 200 East in downtown Salt Lake City. The commercial space’s stated goal is lifting up established and emerging modern contemporary artists “who, in compelling and varied ways, reframe our understanding of the West,” reads the gallery’s mission statement.

I think it’s been a shock to a lot of folks how it’s been excused and gone on for a long time. It’s not an isolated issue. It happens everywhere.

Modern West, Stewart explains, is committed to a form of diversity and inclusion that she says was missing in Utah, a majority-white and conservative state that is home to the headquarters of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

“There were so many really great artists that didn’t have representation in Utah because they didn’t have a platform by which they felt they had the power to walk into a gallery and ask for representation. For some of them, we really sought them out,” says Stewart, who adds that she looked for artists at nationwide events such as the Santa Fe Indian Market.

“I really felt like Utah was ripe to have more diversity be part of the art scene,” she says. “I certainly don’t think Modern West started it, but I think we were on the cusp of pushing it forward.”

In addition to founding Modern West, Stewart says that she currently sits on the boards of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, Utah Performing Arts Center Agency, and several state political action boards. While she isn’t a board member of the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, she’s entrenched in the downtown museum—its main gallery is presented by the Stewart Family Foundation, which champions arts and arts education. Diane and her husband Sam Stewart established the foundation in 2002.

According to its website, the foundation has supported more than fifty organizations, such as the LGBTQ equal rights group Equality Utah, the Mormon Arts Center in New York, the Rape Recovery Center in Salt Lake City, and some of Utah’s biggest arts and culture institutions including Ballet West, UMFA, and UMOCA.

In November 2021, Sam Stewart passed away at age seventy-nine. Many Utahns viewed his loss as a big blow to the community. “We will miss his warmth and humanity,” governor Spencer Cox told The Salt Lake Tribune.

Diane Stewart tells Southwest Contemporary that her daughter passed away from a brain aneurysm six weeks after her husband’s death. Stewart, who says she semi-retired from Modern West in September 2021 to care for her husband, admits that the losses have taken a toll and diverted her attention from the gallery.

Schenck has been a Modern West mainstay from the gallery’s inception through its 2019 move to its current location at the western fringes of downtown at 412 South 7th West. His landscape paintings were prominently featured on the gallery’s ground floor when Southwest Contemporary visited the sunny space in February 2022.

Schenck’s works have been showcased elsewhere in the state. In early 2022, the Southern Utah Museum of Art in Cedar City mounted the exhibition Billy Schenck: Myth of the West, which was paired with Andy Warhol: Cowboys and Indians.

The Warhol exhibition displayed the artist’s portraits of historical figures such as Sitting Bull and Teddy Roosevelt—Warhol became fascinated with American West figures shortly before his 1987 death. Schenck’s show included portraits of rugged cowboys and caption and thought-balloon paintings reminiscent of comic book scenes.

Together with Mark Klett, Tony Foster, Byron Wolfe, Stephen Hannock, and Kent Monkman (Cree), Schenck is part of a cohort of 20th- and 21st-century American cowboy artists, writes Mindy N. Besaw in her 2015 dissertation “Re-framing the American West: Contemporary Artists Engage History.” Schenck’s artworks are particularly sought-after by collectors of American West kitsch—one of his paintings fetched more than $64,000 at a recent Scottsdale Art Auction sale.

“[Schenck] appropriates images of western subjects to critique our culture’s undying fascination with traditional and romantic notions of the American West,” writes Besaw, who is currently a curator at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas. “Where the Cowboy Artists of America revived and perpetuated a myth they had come to believe was truth through reification, Schenck takes a tongue-in-cheek playful attitude toward the myth.”

We’re doing this work to try to bring some healing back to our Indigenous and Native communities, but we still have these images that set the conditions for a lot of folks to continue to see Native people as objects of fetishization.

However, Moroni Benally (Diné), a government affairs consultant for the Navajo Nation in the state of Utah, pushes back on these types of framings. He says it’s not ok, whether it’s tongue-in-cheek or not, when Native Americans, especially Indigenous women, are depicted as subservient or as “other.”

“One of the enablers of violence within the crisis is how Indigenous people are represented in art, media, and other outlets,” says Benally, who worked with the Utah State Legislature on the creation of the state Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Task Force in 2020.

The government affairs consultant says the task force was formed to combat the disproportionate risk of violence, murder, and disappearance of American Indian and Alaska Native individuals. A recent study by the Urban Indian Health Institute in Seattle shows that Utah ranks eighth in the country for the highest volume of MMIWG cases, and Salt Lake City ranks ninth among nationwide cities.

Benally and his cohort combed through numerous studies, including neuroscientific research that showed that “perpetrators of violence against Indigenous people use the part of the brain that is for inanimate objects and not necessarily for human beings,” says Benally, who is also the coordinator for public policy and advocacy for Restoring Ancestral Winds, a Sandy, Utah nonprofit that addresses issues related to violence in Indigenous communities. “The concern for us at the policy level is to make sure that these images don’t perpetuate and maintain this state of violence against Indigenous people.”

“We’re doing this work to try to bring some healing back to our Indigenous and Native communities,” says Benally, “but we still have these images that set the conditions for a lot of folks to continue to see Native people as objects of fetishization.”

On May 2, about a week and a half after Shanidiin’s Instagram posts and facing mounting anger over Schenck’s works, Modern West sent an email to its artists soliciting comments and thoughts.

“We believe art is an important means in facilitating social change and deeper understanding, and we value your opinions,” reads the email signed by gallery director and curator Shalee Cooper.

“In light of recent feedback on social media regarding Modern West’s representation of Billy Schenck’s caption paintings, and his [2017 self-published] book Navajo Wars, we have been reviewing our positions on appropriation and impact to under-represented populations, especially Indigenous peoples,” continues Cooper’s statement.

Modern West posed six questions to its artists, including, “What are your thoughts about [Modern West] showing a particular body of work by an artist and selecting to not show another body of work by the same artist?” and, “What is the gallery’s role, and the artist’s role, in defending or explaining art?”

The gallery also established a public comments page on its website (though users required a direct link to access it), which has since been deleted. Most commenters stood in solidarity with Native peoples who have sustained generational trauma. Others pointed out that the exhibition suffered from a lack of context when showing potentially offensive work.

On May 13, during one of the controversy’s lowest points, the gallery ceased representation of Jorge Rojas, who recently won a 2022 Salt Lake City Mayor’s Artists Award.

The irony is that the same gallery that accused me of trying to silence another artist ended our association in an effort to silence me.

Hours before he was dropped, Rojas had sent an email addressed to friends and colleagues about the situation and provided a link to the comments page and a Modern West email address.

“I think it’s important that our community be aware of this situation as it affects all of us directly or indirectly. I’m sharing this with you in case you’re interested in providing your own feedback to [Modern West],” Rojas wrote in an email acquired by Southwest Contemporary. “If you would like to let others know that the gallery is requesting feedback about this, please do so. If you feel so inclined to take a few minutes to offer your feedback, no need to mention that I reached out to you, as I have already become somewhat of a nuisance and disruptor from the inside.”

The move backfired. That night, Stewart decided to “cut ties” with Rojas over what she describes as a “sabotaging process.”

“Jorge took it upon himself to send an email that he did not tell us about, nor include us in, to his friends and to artists, asking them to inundate us with negative comments,” says Stewart. “I said, ‘You not including your represented gallery in the process was not partnering with us.’”

Rojas declined comment when contacted by Southwest Contemporary. However, he provided a public statement, which in part reads, “The irony is that the same gallery that accused me of trying to silence another artist [Schenck] ended our association in an effort to silence me.”

Stewart admits that the optics of the decision may not have been the best, but remains steadfast in her choice. “You’re right that the timing was quite unfortunate,” she says, “but we can’t be engaged in this process and have artists that we represent undermining us.”

The entire outcome of this whole experience has been negative for everyone.

In a May 15 Instagram post signed by Stewart and Cooper, Modern West acknowledged that “the lack of curation with Billy’s last show was a huge mistake.” However, detractors say that the prepared statement read like a half-hearted attempt at reconciliation that centered Schenck rather than the folks who say they are retraumatized by these types of artworks.

Later in May, around the same time that the gallery called off a public opening reception for a group show out of safety concerns, Modern West decided to “pause” its representation of Schenck.

“In seeking comments, what we have now understood is that some Indigenous people do not want a white person speaking for them. They wanted to tell their own story with their own sensitivities and experiences, which I 100 percent support,” Stewart explains to Southwest Contemporary.

“It was kind of presented as if we received so much negative feedback that we were backed into a corner and had to drop Billy. That is not at all what happened,” continues Stewart. “We solicited comments on our website so that we could make an informed and balanced decision in regard to representation.”

Stewart says that she offered to set up a panel discussion—and even would’ve flown Schenck to Salt Lake City—but “some of the people who have done the most name-calling have refused to be in the same room with him,” says Stewart, who adds, “The entire outcome of this whole experience has been negative for everyone.”

“I really do welcome other voices in the gallery. I think this has devolved into a lot of name-calling and misquotes and people saying things that they’re half informed on,” explains Stewart. Both Stewart and Schenck say that it speaks to the toxicity of social media rather than an attempt at productive, even-tempered dialogue.

I’ve had several conversations with white artists, and they don’t get it. I think because they have been taught not to get it. I know for a fact because I feel like that’s what I was taught.

Laura Sharp Wilson, a white visual artist originally from New York and New Jersey and now based in Salt Lake City, was a Modern West artist in residence earlier this year. Despite the positive experience of her residency, she pulled her work from the gallery—partially because Rojas, who she considers a friend, was let go.

“I thought that was ridiculous,” says Wilson. “Obviously, what we really need is conversation, and that was not conversation.”

When the Modern West controversy started escalating, Wilson thought that it might be best to follow the lead of what Native people had to say before she spoke up.

“And that made me realize how completely wrong that is. We are at a time when white people need to be the ones that are saying this is not okay,” says Wilson, who posted a comment on the Modern West thread saying the gallery should move on from Schenck. “It really struck me, as a white person, the way I [initially] responded.”

“I’ve had several conversations with white artists [about Modern West and Schenck], and they don’t get it,” she adds. “I think because they have been taught not to get it. I know for a fact because I feel like that’s what I was taught… I can’t even point the finger at individuals like Diane or Billy because they’re just doing what has been done.”

Billy Schenck lives and works at a ranch-style property, complete with a rodeo arena, outside of Santa Fe where he and his partner care for horses and cattle. The artist, who has carved out a successful career as a painter, says that he’s a provocateur whose work recasts complicated and racist regional histories into food for thought that can help viewers question and combat long-held and unfortunate narratives.

“You have to know your social or political history to understand what it is I’m doing,” Schenck tells Southwest Contemporary. “It’s not frivolous. It’s not superficial. They’re skimming across the surface, and they have no idea what the context is. They don’t understand it.”

“I’ve been doing this for fifty-two years… there is no artist in the history of the world who has done as much self-deprecating humor as I have,” Schenck adds.

Schenck was born in 1947 in a small town near Columbus, Ohio, attended the Columbus College of Art and Design, and received a BFA from the Kansas City Art Institute. According to biographical information, the artist moved to New York in his 20s to soak in the works of photorealist, color-field, and minimalist painters. At age twenty-four, Schenck sold out his first solo show in New York.

The artist—whose bodies of work include landscape paintings and depictions of frontier cowboys via the halftone dot method—says that he started creating caption paintings around 1979. He often works from photographs, which he reimagines through a paint-by-numbers technique on canvas.

You have to know your social or political history to understand what it is I’m doing. It’s not frivolous. It’s not superficial. They’re skimming across the surface, and they have no idea what the context is.

For the painting showing the village in shambles, which has since sold, Schenck explains that the borrowed black-and-white photograph from mid-20th century Hollywood is problematic from the start, and that the white woman’s response (“Oh my god!! Was that your village?”) is also inappropriate. This is precisely the point, he says.

“I respond to these issues of social and political commentary as satire in a way to provoke thought [and] to let people be aware that here’s an issue,” he says. “I do it in a way that’s gallows or dark humor, but it gets your attention.”

Schenck adds that one of his former studio assistants, a Native artist, also makes pop artworks that are provocative and act as a critical commentary on his own background and culture.

“He gets slammed for it, and it’s very depressing for him, so he backs off because who wants that kind of pressure? It’s just another form of cancel culture,” Schenck says. “Why in the world does an artist have to be edited? You can’t do that. Artists reflect the world they live in.”

When the Modern West debate began taking a life of its own, Schenck says that a solo show of his caption paintings was withdrawn and an art magazine article was nixed. He thinks it’s an ironic development considering his longtime support of Native people—he says that he has financially compensated Navajo guides at Monument Valley and Canyon de Chelly National Monument since 1988, as well as Native people he has photographed.

“I’ve known some of these individuals for years. At one time, I knew every family that lived out in Monument Valley, and they all were appreciative of my work and my career. Other Native artists have seen the humor and taken it in the light when they saw my caption [paintings],” says Schenck, who adds that he has donated money to the pandemic-ravaged Navajo Nation. “I didn’t make a public notion of that to anybody. I didn’t tell anybody.”

Natchez, who runs his own gallery in downtown Santa Fe, has exhibited at Modern West and side-by-side with Schenck in the 2016 two-person exhibition Pop Art from Santa Fe in Madison, Wisconsin. The Tataviam artist, who borrows from pop culture, often paints mixed-media works in loud colors with rabble-rousing subject matter that doesn’t always sit well with the viewer.

People got to understand that in Indian Country, we’re divided as well. There’s a wide view of ideas and subject matter where we don’t all think the same.

While Natchez doesn’t take offense to Schenck’s caption paintings, he did find some of the works in need of some additional finesse, especially in a piece that he says depicts a Native woman topless in a canoe (Southwest Contemporary was unable to locate the artwork image or title). “How can you leave her with some dignity?,” wonders Natchez.

“I think that when non-Indians do Indian subject matter, they definitely should be conscious and way more sensitive to the time that we live in,” says Natchez. “You have to remember that Indian humor is way different than white humor. It doesn’t go across the board.”

“People got to understand that in Indian Country, we’re divided as well. There’s a wide view of ideas and subject matter where we don’t all think the same,” adds Natchez.

Division on a national scale erupted in the art world during the 2017 Whitney Biennial when New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art exhibited Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till, the teenage victim of a 1955 barbaric lynching in Mississippi for allegedly flirting with a white woman.

Schutz, a white artist, defended the work, telling the media that the painting called attention to social issues such as state violence against Black men (“I don’t know what it is like to be Black in America but I do know what it is like to be a mother,” Schutz told The New York Times). Others protested and argued that the work should be removed from the high-profile exhibition, especially if Schutz profited from the piece.

In March 2017, the artist explained to Artnet News that Open Casket (2016) would not be sold. In response to the public debate surrounding the work, the Whitney hosted an event on race and representation featuring discussions with artists, critics, and scholars the following month.

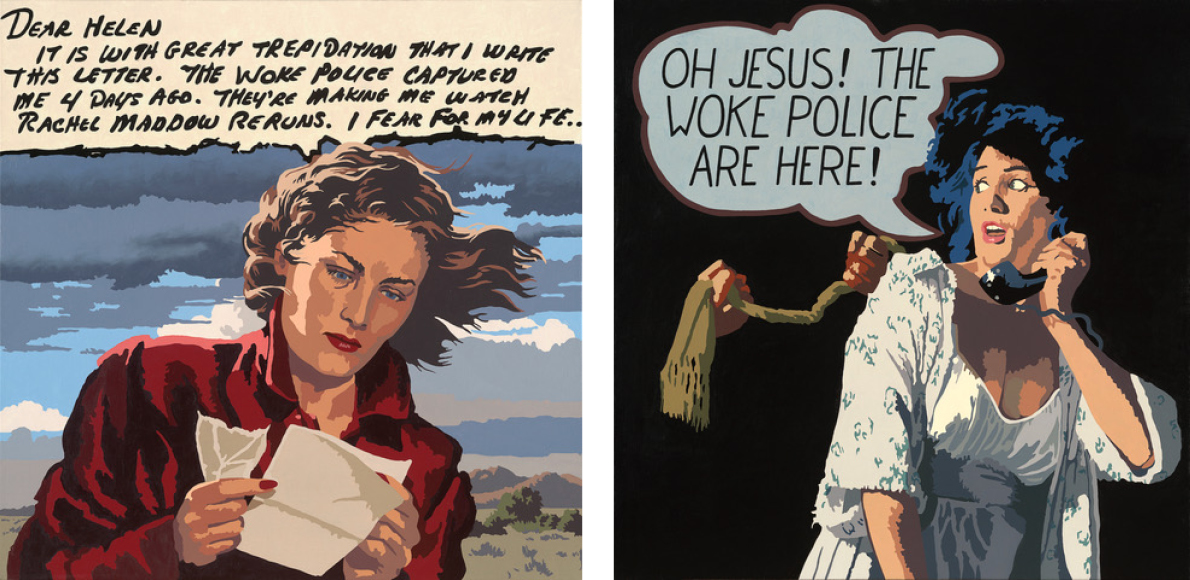

Schenck says that cancel and woke culture have spiraled out of control—he recently painted The Woke Police (2022), in which a fearful woman says into a phone, “Oh Jesus! The woke police are here!,” and emailed an image of the work to liberal political commentator Rachel Maddow (he has not received a response)—and cites the recent Philip Guston controversy as an example.

In 2020—and in light of the country’s social reckoning following George Floyd’s murder—the National Gallery of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and London’s Tate Modern delayed a major traveling retrospective of Philip Guston over the late Canadian artist’s renderings of Ku Klux Klansmen. Swift controversy met the postponement announcement, with several formidable art-world figures opposing the decision, saying that art shouldn’t have to placate or hold viewers’ hands.

“When he started [painting] those hooded figures, he was speaking from his own personal experience of what he saw growing up in LA,” says Schenck, who says he sees similarities between the Guston tumult and the Modern West dispute. “He saw all kinds of racial tensions and anti-Black stuff. It terrified him as a kid to see the Ku Klux Klan marching around. He was Jewish, and he saw plenty of antisemitic stuff growing up.

“He referred back to that stuff. That’s what he was doing when he was painting these things,” continues Schenck. “Then here come all of these [people] attacking him saying, ‘We don’t want these Ku Klux Klan figures’ and, ‘He’s a right winger.’ No, he’s not. He’s reflecting on the terror that he personally saw growing up. You guys didn’t bother to flip the page and look at the context that he’s working from.”

Organizers of the Guston retrospective originally rescheduled the exhibition for 2024, but after pushback, the retrospective debuted in Boston in May 2022. The show, which is currently on view in Houston, has received favorable reviews.

Alastair Lee Bitsóí, a Diné journalist and former reporter with The Salt Lake Tribune, says he was canned from the state’s largest newspaper over a minor technical error. The print edition of his May 26, 2022, article about Modern West and Schenck, which focused on MMIW concerns, incorrectly suggested that Schenck’s controversial, online-exclusive exhibition hung inside the brick-and-mortar gallery. “Those works were never displayed in the gallery and only appeared online,” reads a correction appended to the story’s digital version.

“My editor tore me apart over that little detail and told me it messed up the whole story,” says Bitsóí, who adds, “It’s obviously a lot of work when it comes to cultural competency and sensitivities of Indigenous narratives. I realized that they weren’t ready for a person like me to tell these stories.”

When contacted by Southwest Contemporary, Lauren Gustus, executive editor of The Salt Lake Tribune, wrote, “Employee records, including personnel matters, are not public and as such we have no comment.”

In late September, Modern West stirred Schenck back into the mix by adding his paintings—mostly landscapes and a few caption works that don’t portray Indigenous people—to the gallery’s website.

“We’re going to carefully curate, and if there’s something that we think he’s done that might need a discussion and might need more curation, we’re going to invite people of color to be a part of that so that there’s a conversation,” says Stewart of Modern West. “We’re going to do that with a lot of artists. We want everybody to feel like they can have a voice in what we’re doing.”

As Native people, Shanidiin and her partner Kalama Ku’ikahi Tong (Kānaka Maoli, Chinese), who is also a part of the MMIWhoismissing group, are especially pained by the country’s long and sordid history of looting, hoarding, and profiting from Indigenous artworks and subject matter.

“That’s a big hurt in itself within the Native community. We see our artworks as spiritual beings [and] extensions of ourselves and our identity, our culture, our language,” says Shanidiin. “Often, that sacredness has been taken for the white gaze for capitalism in which people can exploit this beautiful Indigenous land. They have no connection to the land other than being a settler and creating these artworks that comment on settler colonialism.”

“From my perspective, too, as an Indigenous woman, we are always standing alone fighting these issues,” adds Shanidiin. “Because of that abuse that’s depicted in the artworks, when I myself or other Indigenous women speak out against these issues and the harmfulness, it’s often just left, and more abuse is followed.”

Shanidiin and Tong say that a positive aspect of this whole mess is how the Salt Lake arts community has rallied and begun to, in Shanidiin’s words, “dismantle harmful practices” that trigger and retraumatize some Native people.

But it’s perhaps one of the only shining lights, not only for the activist couple but also for the members of the Salt Lake arts community who have been impacted by the incident. Tong, despite the upsetting circumstances, has tried to imbue his own humor into the situation while taking a wide-ranging viewpoint.

“It’s a brilliant case study on whiteness and privilege and appropriation, but also the theft of narratives, especially Indigenous narratives and retelling of cultural and visual histories,” says Tong. “There are so many layers. It could be a fascinating topic for a university class one day.”