La Trampa Gráfica Contemporánea in Mexico City and Familia Printshop in Dallas engage in a long tradition of Mexican printmaking. The two print shops also illustrate the power of collaboration.

This article is part of our Collectivity + Collaboration series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 5.

Ernesto Alva, La Trampa Gráfica’s co-founder, turns the large captain’s wheel. Everyone in the workshop gathers around the gigantic printing press in the center of the room. If it weren’t for the rock music coming out of the speakers above my head, you could hear the proverbial pin drop. Alva turns the wheel one way, and once the press bed reaches its maximum extension, he turns it the other.

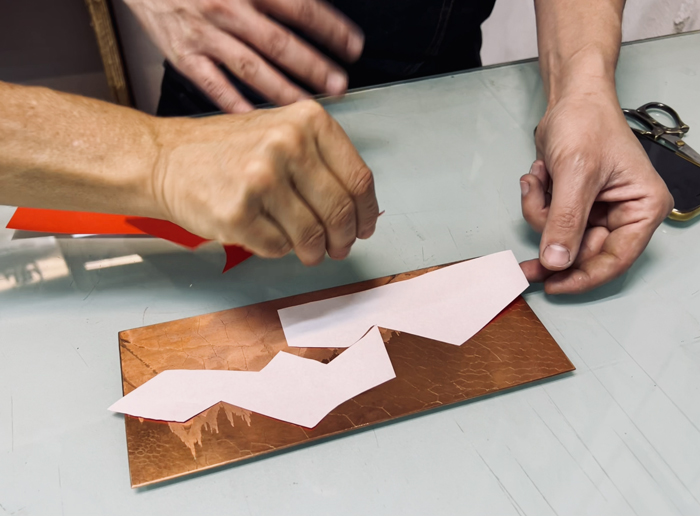

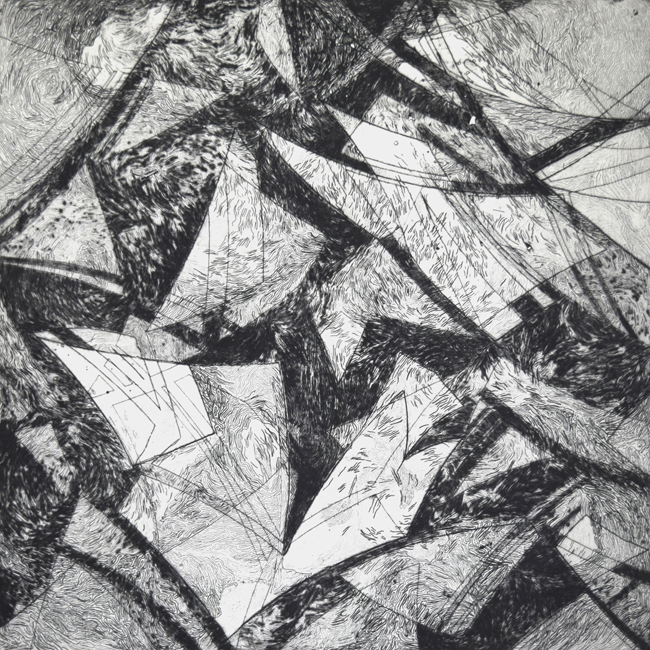

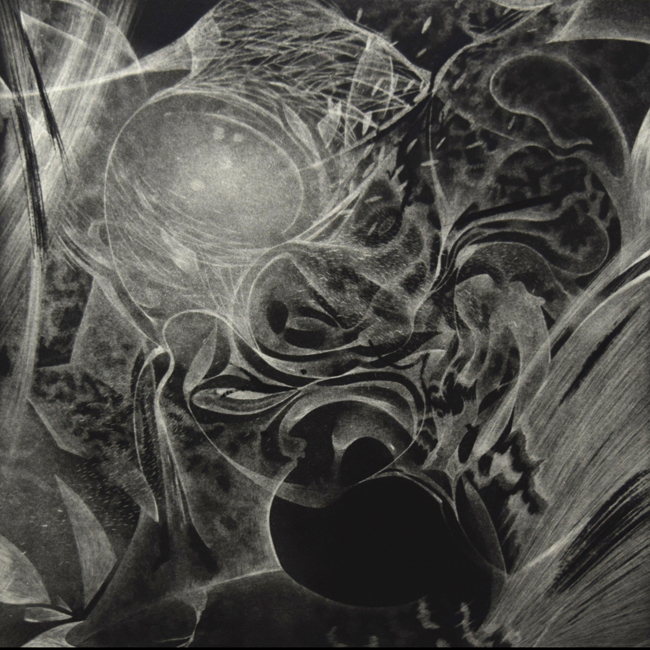

His partner, a printmaking artist originally from the state of Oaxaca, Alondra Bénitez, lifts the woolen etching blanket off the press bed, and uncovers a wet paper, face down, atop a copper plate. Bénitez gives Iris Barrera—whose etched copper plate it is—a look, and says, “Lista?” Barrera, an Argentine artist who spends several months per year in Mexico City, nods. Bénitez lifts the paper, ever so slowly so as not to move the inked copper plate beneath it.

Barrera laughs a little and cringes, and Bénitez, alongside Alva, inspects the print. It did not come out the way Barrera had hoped. An extra space, where there should be none, appears between the golden color from the metallic paper Barrera had superimposed on the copper plate, and her original print.

Four other artists gathered around the press and huddled around Barrera and her work. They inspect the print without touching it, gesture with their fingers, and throw in ideas on how to fix the problem. The paper is too wet. What pressure did you use? Is the metallic paper made of cotton? Did you stick it with glue to the plate? Barrera nods and shakes her head. Takes it all in. She goes back to the large table near the press to clean the plate and start again.

Barrera’s artwork may ultimately belong to her, and bear her name, but any work that she produces at La Trampa Gráfica Contemporánea in the historic center of Mexico City is also an exercise in and the artistic result of group collaboration.

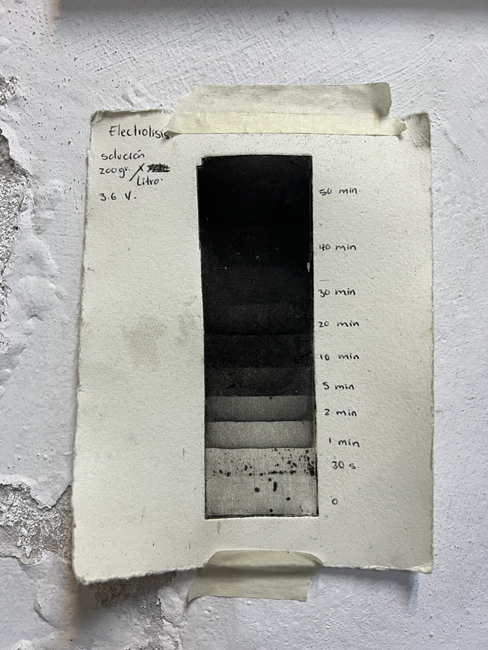

Ernesto Alva, a master printmaker and La Trampa’s sole remaining co-founder, wouldn’t have it any other way. Neither would any of the workshop’s regulars I met over two weeks as I learned etching and aquatint.

Alva studied printmaking at La Esmeralda, or rather, La Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado, the National School of Painting, Sculpture, and Printmaking in the capital, and Mexico’s most famous fine arts school. He had studied painting for years at a pre-college fine arts institute, and dabbled in printmaking—his skills, however, were already winning him awards. He failed his Esmeralda interview the first time he applied, though, because, as he put it, he lacked maturity and humility. Not anymore, he doesn’t.

“When I finally got in and had to pick between studying painting and printmaking [at La Esmeralda], I picked printmaking because of how social it is.” Painting, he explains, “is often a lonely exercise. You can do it solito.” All alone. On your own. Printmaking, on the other hand, especially the Mexican approach to grabado, is a collective act.

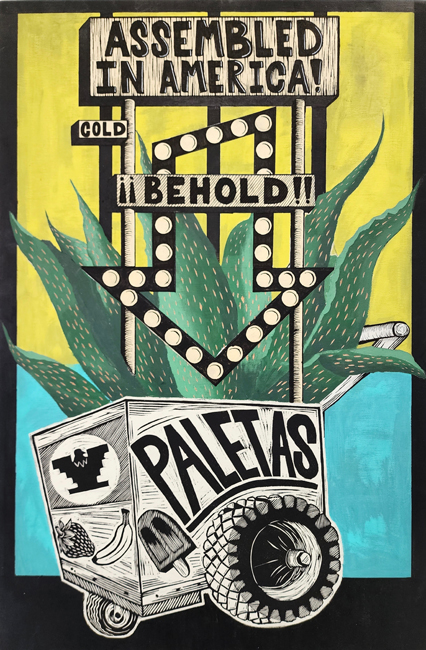

Benjamin Muñoz, co-founder of Familia Printshop, a printmaking collective and the only one of its kind in Dallas, would agree with Alva. The Chicano artist, who trained for a long time in painting techniques, first stumbled on printmaking during his fine arts undergraduate degree in Corpus Christi when his advisor encouraged him to take printmaking fundamentals.

“When I walked into the print shop, it felt a lot like a skate park,” says Muñoz, who grew up skateboarding every day. “Everybody hung out. And there was the sharing of knowledge and process like at the skate park. You know, if you want to know how someone did a trick or something, they’ll tell you, they’ll show you, they’ll walk you through it.”

Printmaking is an expensive endeavor. Etching and litho presses sold by Takach, a press-making company in Albuquerque, sell for anywhere from $6,000 minimum to about $30,000. The press at La Trampa, back in Mexico City, would have cost Alva an arm and a leg in 2009, and maybe even his soul, had a printmaker-turned-painter friend of Alva’s from La Esmeralda not lent it to him. “Hopefully forever,” says Alva. The friend had won it in a printmaking contest, but the less said about it, Alva tells me, the better (in case the friend ever wants it back).

Then come all the other costs, says Muñoz: drying racks, large tables, a good ventilation system, and most importantly, space, and lots of it, because you can’t move your heavy printmaking equipment at will.

Printmaking is, at its core, a medium that requires collaboration. “Collectively, we were able to put it all together,” says Muñoz. None of his colleagues, and neither Muñoz, could have done this on their own.

But the collaborative aspect of a printmaking collective, however, goes beyond sharing costs. Even UNM’s elite Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque promotes collaborative printmaking between artists and printers, not unlike at La Trampa. Alva and Cesar Catsuu López, the other co-founder of La Trampa, opened their workshop in 2009 as “an artistic lab, a space of collective participation, a point of meeting between colleagues, friends, and others interested in artistic and technical exchange.” Muñoz, on the other hand, believes that part of printmaking’s goal “is to be with other people and work together.” That’s what community shops are for, he adds.

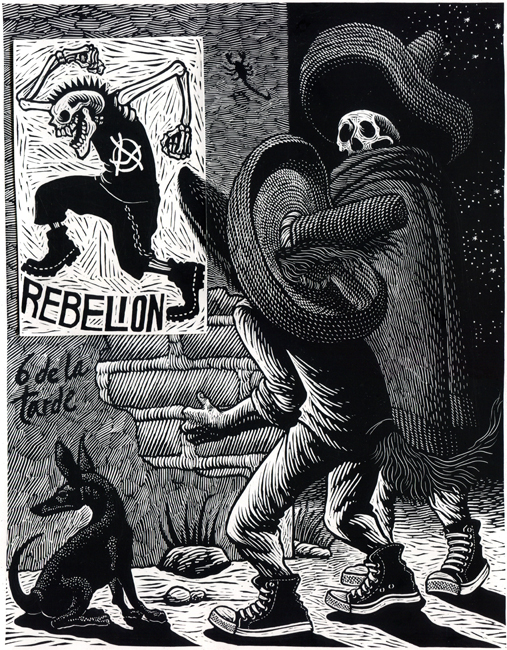

Not every renowned printmaker these days in Mexico is part of a collective, however. Sergio Sánchez Santamaría first learned printmaking at the Taller de Gráfica Popular (The People’s Print Workshop), founded originally in the 1930s, when printmaking was still an implement of political upheaval. After the artist, originally from Tlayacapan, graduated from La Esmeralda in the late ’90s, he formed a printmaking collective that dissolved a year or two later. Which, in retrospect, worked out well for him as he soon found another collective to work with, and one that changed his life: a printmaking workshop where some of the greatest Mexican grabadores of the 20th century worked. His first printmaking teachers there were Alfredo Mereles as well as Jesús Álvarez Amaya, who had been Diego Rivera’s assistant. Later, he learned from and worked with Alberto Beltrán and Adolfo Mexiac, two other legendary artists. Sánchez Santamaría sometimes slept on a small mat in their workshop, where he learned by observing the old masters. They’d cook for him, and he’d assist them in their work.

Since the last of his teachers passed away a few years ago, Sánchez Santamaría has been an orphan of sorts, as he puts it. Today, he mixes the modern and traditional, and critics in Mexico refer to him as the godson of Mexico’s old printmaking tradition. He now owns his own iron cast printing press, which he calls “El Jaguar,” and another one, “El Chile,” this one specifically for proofs. He has two workshops but reserves them for his own creative use: one in Mexico City and the other in Tlayacapan. As an artistic orphan, he works more often than not on his own.

When I ask Sánchez Santamaría whether he belongs to a printmaking collective, he shakes his head. I mention that perhaps his collective was that of his old masters—at which he smiles, one of those big smiles illuminating his entire face, and says, “Sí, supongo que sí.”

I suppose that they were my collective.

Both Sánchez Santamaría’s and Muñoz’s works are represented by Hecho Gallery and Hecho a Mano in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The galleries primarily showcase work by Mexican, New Mexican, and Chicano printmakers. They may not be a collective per se, but the regular exhibitions at both Hecho Gallery and Hecho a Mano give the galleries a sense of printmaking togetherness.

Back at La Trampa, Barrera, the Argentine artist, is deep at work on adding different colored papers to her copper plate to experiment with. I sit in front of her, at the same large table, scratching my own plate which is not coming out as I wish it had.

An elderly gentleman comes in, with a large box in his bag, like an oversized backpack. It’s full of pineapple juice, and we all pitch in to get a cup. For a moment, I, too, though still a stranger, feel part of the collective.

As I drink my juice, Alva and his partner, Bénitez, notice my despair at not knowing what to do to better my etching. One of them takes the plate and smears it with oil-based ink, cleans the extra ink off with a cheesecloth. Alva then covers it with paper and passes it through the printing press. I have no say in the process or the time it takes to do all of this. Which is scary, to be honest, and embarrassing because I’m still a novice, and also because I may be too much of an individualist. I need to let go.

And I do. This collective act can be freeing, and as I watch the printing press in motion, I allow myself to just go with it. I allow the I to become a we. And, the pressure of a perfect print is off my shoulders, even if for a moment, because others in the workshop shoulder it for me.