Ecstatic Land at Ballroom Marfa proposes an expanded definition of the landscape genre by assembling a transgenerational group of artists for this exhibition and film series.

Ecstatic Land

October 26, 2022–May 7, 2023

Ballroom Marfa

Cultural critics have long inventoried the inextricable ties between the Western landscape genre and larger notions of cultural and capital domination. Ecstatic Land, a group exhibition and film series at Ballroom Marfa through May 7, 2023, seeks to imagine alternatives. The exhibition’s co-organizers, guest curator Dean Daderko and curator and director of Ballroom Marfa Daisy Nam, highlight contemporary artists who treat landscape as complex embodied encounters where the internal self and the external site meet.

Dineo Seshee Bopape’s monumental sculpture, Lerato le le golo (… la go hloka bo kantle) (2022), presiding at the center of Ballroom’s North Gallery, cements Ecstatic Land’s physical and poetic locus. Hand-smoothed, circular walls—constructed by local artisans and assembled from earth collected from Marfa and mixed with healing plants—invite visitors into a warm, sheltering arc. Mechanical, natural, and musical soundscapes by White Mountain Apache musician-composer Laura Ortman drift irregularly over the space. Unfolding into a crescendo of strings, Ortman’s sound installation resonates with the celebratory timbre of Bopape’s sculpture, whose Sepedi title— “a great love… that has no outside”—further ensures that Lerato le le golo’s earthen deposits in the gallery are worlds apart from Walter de Maria’s Earth Room (1977).

This is not to say that Ecstatic Land entirely escapes the specter of 20th-century Land Art. Nancy Holt’s (1938-2014) Star Fire (1986), a grouping of fire pits dug into Ballroom’s Courtyard, mirrors the Big Dipper. Holt envisioned carrying celestial bodies down to earth when the pits were activated by fire; fittingly, each pit, now extinguished, resembles a different moon phase as the sun casts shadows along their metal enclosures, partially illuminating and transforming the floor’s grainy, ashen residue into miniature lunar surfaces.

Back inside, Holt’s Electrical Lighting for Reading Room (1985) commands one end of the North Gallery. With its sprawling metal conduits and brightly glowing bulbs, the work’s link to “landscape” may puzzle those unfamiliar with Holt’s oeuvre. Its inclusion, however, deftly underscores a preoccupation shared by many of the exhibition’s artists—technology’s mediating role in bridging shared, external environments to one’s individual, internal landscape.

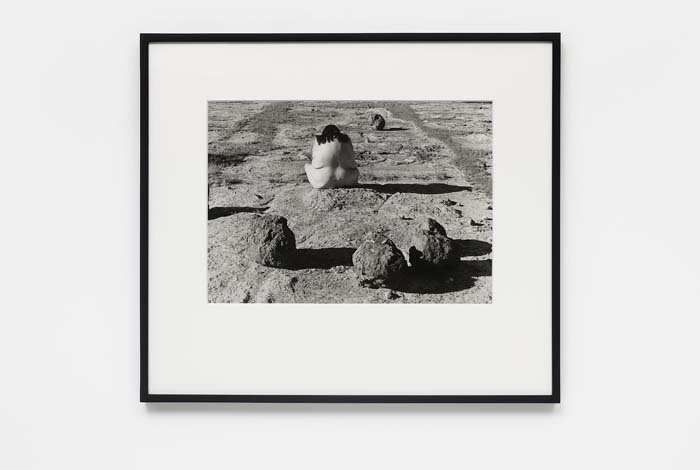

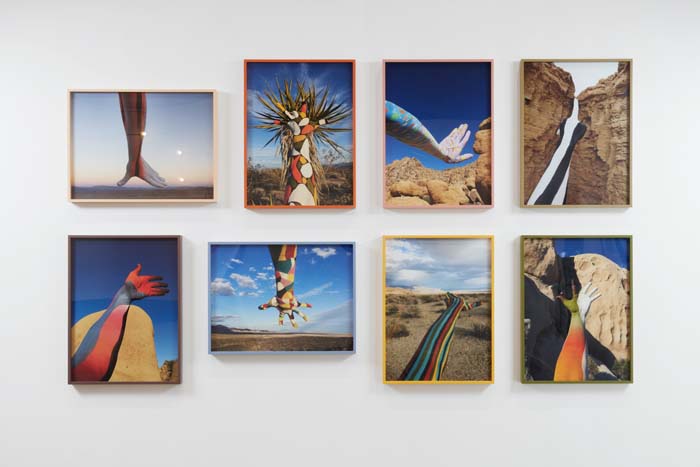

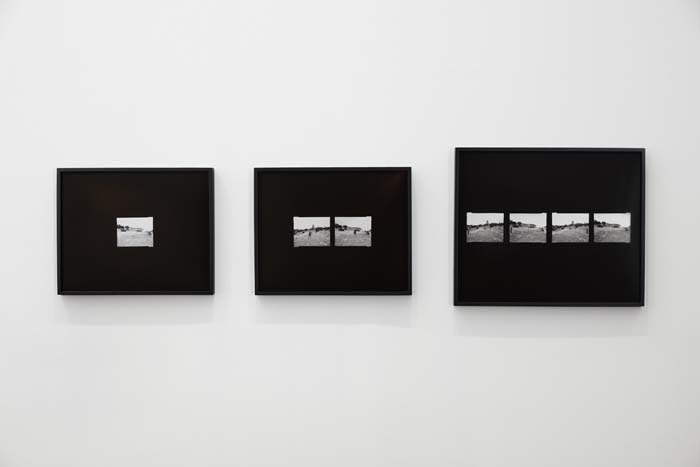

Exquisite gelatin silver prints by Katherine Hubbard center both the photographer and her equipment as subjects, inverting early landscape photographers’ tendencies to erase the processes involved in framing grand vistas. Benny Merris applies paint directly to his body, documenting compositional serendipities where lines of pigment and topography intersect. A quartet of Laura Aguilar’s (1959-2018) photographs gracefully interfuse her large, sensual frame into the surrounding terrain, a mutually enlivening affirmation of queer belonging on an intimate scale, while David Benjamin Sherry queers familiar, outsized images of the American West in teal and violet chromatic explosions.

Despite the seismic aesthetic shifts from the 19th century’s romanticized views of the American West to the earth art interventions in the 20th, the impulse toward spatial conquest has yet to wane. By complicating the terms of landscape, Ecstatic Land’s strength is its more generous vision, proposing an expanded tactical menu to reconcile the corporeal subject and the living space it inhabits. It remains a dream as broad as the Marfa sky.