Simone Johnson writes about her experience living between New York City and Arizona, while also highlighting her explorations of water and time in the Colorado River Basin.

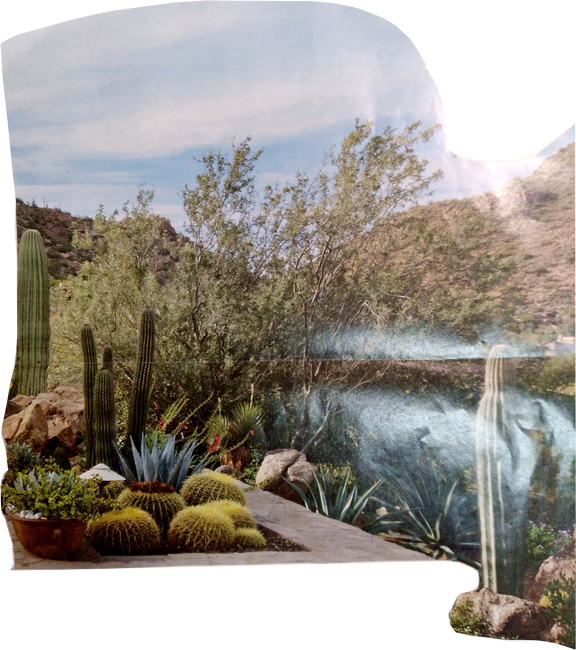

Navigating life mostly through a watery lens, I came to the desert ecosystems of Arizona—where there are mesquite trees and mesquite honey, river otters, wetlands, and red-brown soils, hummingbirds, cactus flowers, and plump citrus fruits growing in front yards—and feel I have traveled to another world in the aquatic universe.

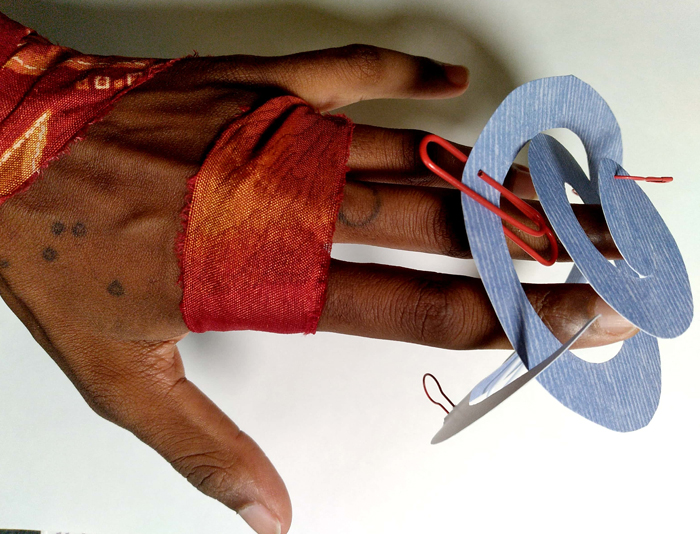

My water futures practice originates in New York City, where I was thinking a lot about the relationship between sea level rise, flooding, and wetlands, playing with the idea of the swampy-marshy-tropical spacetime continuum and wetland imaginaries. When I traveled through a portal from New York to Phoenix a year or so ago, I had no idea how my water futures practice would change. But I knew I would continue what writer Bayo Akomolafe calls “an activism of inquiry”—asking questions as a form of art, activism, and cultural work.

CONTEXT

Sometimes I feel self-conscious when I tell the story of how I grew up, because it’s not neat or linear. First, I am being raised by mountains in small Colorado cities, and then at the age of twelve, my tender dangling roots are transplanted to New York City, and eventually Staten Island. When I think about who I am, it is someone who has grown up in a coastal city, on an island near the Atlantic Ocean.

Living in Arizona, the landscapes and my social relationships are drastically different. One moment I am taking the Staten Island Ferry, thinking about oysters in New York Harbor, then I am walking past a mystical ocotillo plant to get the mail in dry heat.

During my time in the Southwest I have been researching the relationship between water and spacetimes in the Colorado River Basin. In a Time Glossary, I have collected words, phrases and sayings related to time. For example: memory and deep time, future histories, multispecies time zones, glitches, déjà vu, entropy, presence, and “making time.” One of my core research questions is, in what ways can we apply words and concepts about spacetimes to water? For example, pipeline protests, spills and déjà vu, farmers in the West, water use and future histories, or the literal act of “making time” for things we think we do not have time for—like difficult political conversations.

I offer this essay from my perspective, an element of time I have been playing with personally and artistically. I feel that Perspective is a powerful technology in understanding the world and approaching a situation or way of living. One of the easiest ways to activate this technology is to seek out various perspectives.

TIME ISN’T REAL

Journalism covering the Colorado River abounds. There are headlines like “Running out of river, running out of time” and “The West’s water crisis is worse than you think.” Though alarmed, I’m grateful for regular water journalism. The constant news about water security has shaped my orientation around land and water in Arizona, which is located in the Lower Basin along with Nevada and California.

Even when I lived in New York City, with the Hudson River as my home river, I still found myself downriver. I realized I needed to pay attention to what was happening upstream, so I started following the work of the Hudson River Watershed Alliance.

Equally, I realized that I needed to pay more attention to water journalism in the Upper Basin, which includes New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah.

“TIME WILL TELL”

Over the last year I have contemplated many things, including:

The life of the Colorado River, who takes care of forty million people, and the toll of climate change, drought, and overallocation on its body and psyche.

Although I don’t know the Colorado River, I still feel grief for this river, and all waterways who are overallocated, exploited, dammed up, polluted without a second thought, buried, forgotten, or socially neglected, and how this ripples out to the rest of the web of life.

When it rains, I wonder if it’s raining “naturally”, or if clouds gracing the sky have been artificially seeded, and I imagine a solarpunk future where people reminisce about “real” rain.

Then there is groundwater or aquifers—literal water futures held in the fertile darkness of soil with the spirits and humor of rocks.

In Arizona, agriculture takes up most of the state’s Colorado River allocation; however, with increasing water cuts, farmers are now having to grow food on less land with some relying more on groundwater.

Phoenix’s population continues to grow, real estate development continues to expand, and thanks to the approval of new data centers, which use millions of gallons of water each day, digital life thrives.

If it isn’t already overwhelming, all of this is on top of living in an imaginary borderland where the Colorado flows into Mexico, with intense political debate about borders.

STORIES

When I walk along the Eastern Canal near the Riparian Preserve in Gilbert, Arizona, I go back and forth thinking about what words and narratives I want to carry that describe what is happening here in the basin—perspectives and stories that I don’t want to be disempowering, yet honor the physical truth. Words and stories that, in the midst of a worsening water crisis, generate wonder, awe, curiosity and feed our ecological imaginations—if that can be a remedy at all. I imagine having a long frown and feeling frustrated, looking up and confiding in a cottonwood tree, who comforts and tells stories too.

TIMELINES-TIMECIRCLES-TIMESPIRALS

Rummaging through my time travel gadgets, I find what I’m looking for. Let’s go to 2024! I am a bird flying in the wonder of the sky, sometimes causing glitches. There are new and stronger narratives about water rights expressing themselves differently than the year before. Do you know what these stories might be about?

As a cultural worker, I am interested in mapping interdisciplinary water work ecosystems, and getting a bird’s eye view of regional narratives and narrative power.

Historically, Native communities have been left out of conversations and decision-making about water stewardship in the basin, but this is changing.

The Ten Tribes Partnership is “a coalition of Upper and Lower Basin Tribes that have come together to claim their seat at the table and raise their voices in the management of the Colorado River as water challenges persist.” And with the state of the river today, I have been thinking a lot about Indigenous Futurisms, especially in tandem with Indigenous laws and legal traditions, and Earth Jurisprudence.

“THE FUTURE” IS NOW

If you can’t tell by now, I am a futurist. It’s always important to say that the future is now, and we don’t have to compare or privilege one domain over another—it’s all one and the same.

Some folks telling stories in water work ecosystems in Arizona and New Mexico include Ecoartspace, where I learned about Tó Nizhóní Ání or Sacred Water Speaks, a Diné-led non-profit protecting the waters in Black Mesa located in Northeast Arizona on the Navajo Nation. There is also Watershed Management Group and Red Star International, both based in Tucson. And in “Desert Water Poetics and Politics,” an online workshop led by poet and Albuquerque-based farmer Mallika Singh, I learned about the history of acequias in New Mexico and Pueblo Action Alliance’s #WaterBack campaign.

In the midst of climate change, there is not one cookie-cutter future for the country; however, I do think there are regional and placed-based futures, and within that, what Black Quantum Futurism calls community futurisms.

MEMORY

It is necessary to remember: that rivers have many names; that rivers need to live too; the Zanjeros in Arizona, who have a twenty-four-hour job taking care of the canals; water insecurity in tribal lands; upriver and downriver relationships and the history and ripple effects of the Colorado River Compact of 1922.

PERSPECTIVE

Artists have been opening up old-new spacetimes for centuries, and in the Southwest there are numerous people and works of art focused on land and water. Parched: The Art of Water is an art exhibition that examines the complexities of water in the Southwest, There Must Be Other Names for the River considers the history, present, and potential futures of the Rio Grande using sound and voice to communicate archives of waterflow data from the river, while Dr. Chip Thomas and Dr. Ken Ogawa address the impacts of uranium mining in Navajo country, and Meredith Nemirov explores trees and maps to imagine the Colorado without drought.

As someone in between the coast and arid lands noticing ecological art and social practice in both places, I wonder about what kinds of ecological solidarity could exist between Colorado River and San Juan River Basin communities, and New York City, including the city’s relationship with Hudson River communities. Although their futures will most likely be different, and it might seem like there is nothing in common, I wonder what kinds of conversations and collaborations could take place?

CHANGE

What if we time traveled to 2028, five years from now? What will the Colorado River be like? What old-new timelines do people want to open this year, in the present? Tools and practices to open timelines-timecircles-timespirals include: generating conversations about doing water stewardship differently; bringing people from different ethnic, class, generational, and disciplinary backgrounds together to brainstorm ideas for a project; or consulting our more-than-human kin to ask them about the past, many of whom are much older than us and will outlive us.

To engage in futurisms does not have to be a siloed experience of disembodiment, anxiety, and fear, but a grounded, present, and communal exercise of creative expression and creative power.