Vivian Horan Fine Art

April 27 – June 22, 2018

Soon after moving to northern New Mexico, almost seven years ago, and after doing a welter of studio visits, I noted the number of exceptional draftspersons in the area and pulled together a proposal for a show of drawings by artists who live in the general area of Taos. When I approached one of the more adventurous galleries in Santa Fe about an exhibition, the dealer bluntly responded, “No one cares about Taos artists.” About a year later, I organized two days of studio tours for a group of collectors from Albuquerque. At the end, a few said to me, “We had no idea there were artists like this in Taos.”

Clearly, to use current media parlance, Taos has an “optics” problem—not unlike Santa Fe, where a certain Canyon Road aesthetic predominates in the minds of visitors. Sometimes you have to hunt through a rockpile of kitsch to find the gems, but they are here, and some have been around for decades.

So it’s a welcome effort on the part of photographer and sculptor Paul O’Connor to pull together a group show of Taos artists for the elegant parlor-floor gallery of Vivian Horan Fine Art on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. This is a small and select offering, but it covers a lot of bases and almost sixty years (roughly 1960 to the present), along with a broad spectrum of media.

Larry Bell, Ronald Davis, Ron Cooper, and Ken Price all picked up stakes and moved from Los Angeles to Taos in the 1970s, bringing with them new materials and new technologies. Davis’s snazzy twelve-foot-long Frame (1969), made from pigmented polyester, dominates the gallery, but Cooper and Bell’s quieter sculptures in Plexi and vacuum-coated glass modestly hold their ground, representing the more minimalist sensibilities among the LA emigrés. The floor space is mostly given over to ceramics on pedestals from Price, Hank Saxe, and Lynda Benglis (who does most of her work in clay in Taos). Kevin Cannon, whose sculptures are made from painted leather burnished to a seductive gloss, offers up a sly Brancusian wit: his Untitled Duo from 1987 could almost be a spin on The Kiss.

It would be convenient for a reviewer to pick out influences and allegiances here, but though O’Connor was a studio assistant to Davis, and Cannon worked briefly with Price, there are no easy affinities, no real trickle-down of sensibilities from one generation to the next.

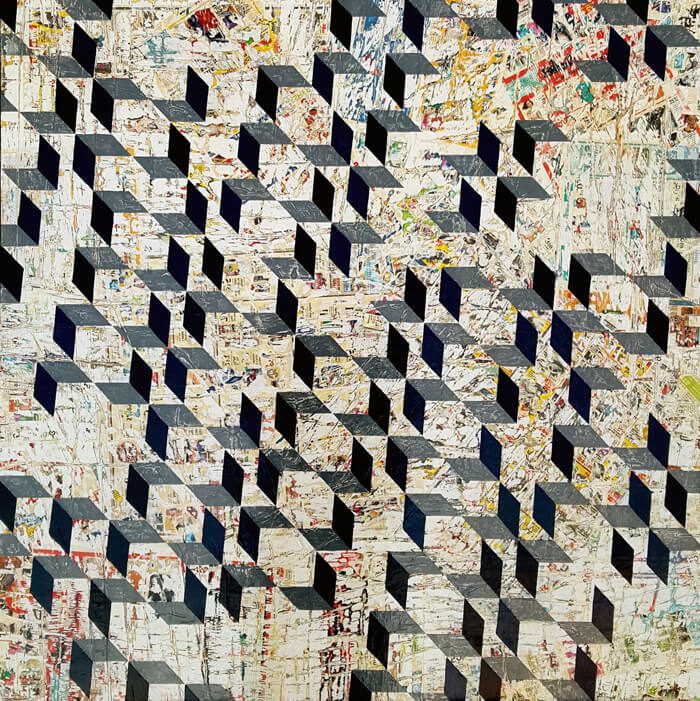

Four one-foot-square lithographs from the late Agnes Martin, serenely modest in this context, hang above the mantel, flanked by three of O’Connor’s relief sculptures in metals and other materials on plywood. Benglis and Sasha Raphael von Dorp both push the boundaries of photography by introducing, respectively, gold leaf and a water-based process to their prints, while Debbie Long’s Tow Package (2010) scatters cast-glass grace notes along one wall of the foyer. Her work, along with von Dorp’s photo and J. Matthew Thomas’s collage of paint and paper on wood, act as emissaries from a younger generation, in their thirties and forties. Tucked away in a corner, Jack Smith is the only realist in the group, represented by three six-by-six-inch portraits in oil on copper plate. Marc Baseman’s etching and three drawings in graphite on paper are like bulletins from another planet, resisting easy categorization, even as they suck the viewer into a frenetic cosmos in miniature.

It would be convenient for a reviewer to pick out influences and allegiances here, but though O’Connor was a studio assistant to Davis, and Cannon worked briefly with Price, there are no easy affinities, no real trickle-down of sensibilities from one generation to the next. It’s simpler to quibble with some of the choices: Larry Bell’s Pink Ladies IV, an eighty-eight-inch-high serigraph of a distorted nude, looks weirdly dated, like a psychedelic album cover from the ’70s, and a photo by Dennis Hopper of dealer Irving Blum and Jasper Johns seems to have no relevance whatsoever. It was also dismaying to see so many terrific artists who didn’t make the cut. But, all things considered, and given the New York scene’s general myopia about art communities outside the five boroughs, the show at Vivian Horan offers a smorgasbord of visual delights and a reminder that there’s more to Taos than meets the eye.