Charged with reviving SITE Santa Fe’s storied biennial, world-renowned curator Cecilia Alemani unveils Once Within a Time, a citywide chorus of regional and global voices.

Once upon a time in Istanbul, curator Cecilia Alemani visited a peculiar institution called the Museum of Innocence. Occupying a narrow 19th-century home, it holds over a thousand objects collected by Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk as he wrote his 2008 novel of the same name. The house is a companion piece, a feat of literary immersion.

“This museum doesn’t tell a universal story, like the Met or the Louvre do about civilizations,” says Alemani. “It’s basically about the life of two characters in one of his novels.” The experience sparked an epiphany: “There should be museums and institutions that actually tell a much more human and intimate story of people.”

Alemani brought this idea to SITE Santa Fe two years ago as they were working to revive their biennial exhibition series, which stalled out in 2018. SITE launched the first-ever American biennial with an international scope in 1995. The new effort is a rebrand of their flagship program as the SITE International, with Alemani as guest curator.

The SITE project came on the heels of Alemani’s work as curator of the 2022 Venice Biennale, the 59th edition of the world’s preeminent showcase of contemporary art. The Biennale is always built around a “major global idea,” and after its conclusion, she was finding it “challenging… to really adjust to a different scale and pace.” Her regular job curating monumental public artworks for the High Line park in New York wasn’t helping.

For the International, Alemani “wanted to do a show about one person—basically tell a bigger story through the eyes of this person,” she says. Then she ran into a dilemma. “When I started doing research on Santa Fe and New Mexico, there were about twenty incredible people that I wanted to choose.”

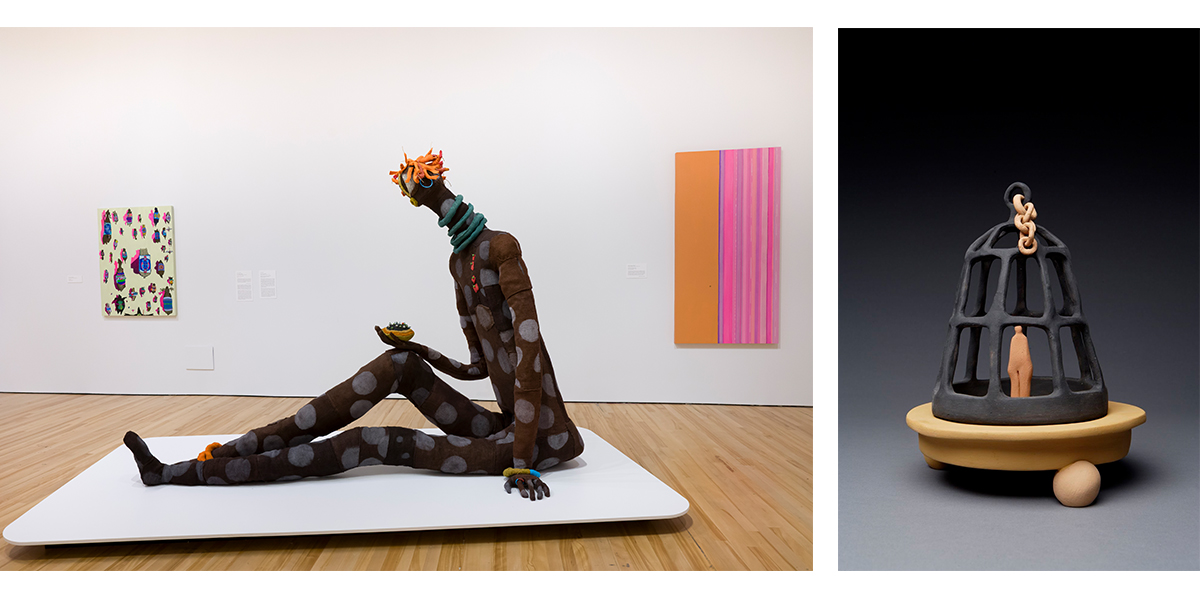

The exhibition Once Within a Time, opening June 27, 2025, and running through January 12, 2026, is Alemani’s maximalist solution. The twelfth SITE International invites seventy-one artists—from local voices to international art stars—to use twenty-seven real and fictional “figures of interest” as anchor points for interpreting Santa Fe’s regional histories.

This pantheon (or “family album,” per SITE’s press release) includes famous and obscure artists and authors, literary characters, and folk figures. Among them are La Malinche, the controversial Indigenous interpreter and strategist at the heart of Spanish Colonial conquest narratives, and Willa Cather, the Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist whose depictions of the American frontier continue to shape perceptions of the Southwest.

Alemani and her many collaborators aren’t crafting straight portraits or biographies of these folks. The show instead “proceeds by analogies and rhymes,” she explains, swirling together over 300 local and international artworks (along with newly commissioned writings, and historical artifacts and ephemera) at SITE and thirteen other venues around the city. It extends into other institutions like the New Mexico Museum of Art, and unexpected spots like a cannabis shop, a toy store, and a city park.

If Once Within a Time coalesces as Alemani envisions it, the exhibition will present not as a history book but a visual symphony.

[In New Mexico] you can really perceive the layers of history just in front of you, like everywhere.

This spring, the local section of Alemani’s orchestra was anxiously tuning up, as an array of New Mexico–based participants prepared projects for the International. Taking a cue from Alemani’s humble early premise, I spoke with just six of the twelve local contemporary artists in the International, exploring how a tightly focused lens can unravel complex historical arcs.

These artists bear the unique weight of interpreting stories from their own communities for an international audience. They will appear beside famous names—notably multidisciplinary artist Simone Leigh, who won the Golden Lion award at Alemani’s Venice Biennale, and experimental filmmaker Sky Hopinka (Ho-Chunk Nation/Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians), a 2022 MacArthur “Genius” fellow who’s currently storming the U.S. museum world.

Through the eyes of New Mexico’s artists, Alemani has come to view Southwestern history as an unusually strong tensile force in the present moment. “You can really perceive the layers of history just in front of you, like everywhere,” she says. “[There’s] this friction. This idea of coexistence, of being a crossroads among different histories and people, is still very much a part of the conversation.”

Diego Medina is thinking about the beginning and the end—as in the very end.

In his former role as a historic preservation officer of the Piro-Manso-Tiwa Tribe in the Las Cruces area, he once visited the oldest-known human footprints in North America at White Sands National Park.

“The footprint site shows us early human presence and relationship to this place,” Medina says. “Then you have the Trinity [nuclear testing] site, which is really close—the theoretical end of time.”

As he dreamed up his project for the International, Medina was watching Once Within a Time (2023), a film by American director Godfrey Reggio that inspired the International’s title. Unofficially, Reggio was the first of Alemani’s “figures of interest” for the International. She was surprised to learn that the visionary octogenarian, known for his experimental Qatsi trilogy, is a longtime Santa Fe resident.

Alemani says, “When I was a kid in the 1990s… I [watched] Koyaanisqatsi at 3 am with lots of friends. I remember the powerful feelings, the ecstasy, these movies gave me.” The documentary-style series seeks out organic flickers of hope within post-industrial hellscapes.

Shot in-studio during the COVID-19 pandemic, Reggio’s Once Within a Time (which SITE will screen during the International) flips the Qatsi script, casting fairytale imagery into an apocalyptic sprawl.

Medina says, “The movie is… undergirded by this theme of eschatology, the consideration of the end times. But it’s looking at this notion of renewal, right? I’m thinking about what it means for the timeline to be collapsed between 20,000 years ago and me in the present.”

Now a full-time artist with a studio near Taos and representation at Santa Fe’s Smoke the Moon gallery, Medina is working on a cycle of figurative paintings referencing the Stations of the Cross and the passage of the Rio Grande across New Mexico, which will appear in the International’s main exhibition at SITE.

“I’m thinking about mythical geography, historical geography, cosmic geography—whatever word you want to throw in front of geography,” Medina says. “How we come to understand an alternative geographical language through… myth and history and story.”

Maja Ruznic is on a literal collision course with some of Santa Fe’s most notorious history paintings. On a video call early this spring, the Placitas-based painter tells me she’s waiting on custom-made stretcher bars designed to slot directly over early 20th-century oil paintings in the St. Francis Auditorium at the New Mexico Museum of Art.

They belong to Utah-born artist Donald Beauregard (1884-1914)—one of Alemani’s twenty chosen figures—who plotted six monumental compositions illustrating the violent arc of Spanish colonization, from Preaching to the Mayas and the Aztecs to Building of the Missions in New Mexico (both 1917). He died of cancer in the middle of the project at twenty-nine years old, and two other painters completed the works.

I was intimidated to respond to this history—I am an immigrant, I’m not even from here.

Ruznic’s rich and gauzy figurations, partly drawn from the emotional well of her experiences as a Bosnian genocide refugee and American immigrant, will eclipse three of the six Beauregard compositions.

The project aligns with Ruznic’s sense of Once Within a Time as “playful… almost like a Samuel Beckett play where there’s no sense of linearity.” Still, preparing for the International has been a daunting process—despite her inclusion in last year’s prestigious Whitney Biennial in New York.

“I was intimidated to respond to this history—I am an immigrant, I’m not even from here,” Ruznic says. “I’m not putting paintings in those alcoves to heal the trauma that happened to the Natives by the Spanish colonizers; no human is capable of that.”

Instead, Ruznic will respond to layers of pain in the space “like a jazz musician,” from colonial violence to Beauregard’s illness. She says, “I think maybe what my paintings will do, and maybe this does not feel too audacious, is create little holes in history… so that something new and strange that we can’t even name can come into those spaces.”

Terran Last Gun (Piikani) would probably join the Transcendental Painting Group—if only the New Mexico art collective hadn’t folded in 1942, just four years after its founding.

“I feel very connected to what this specific group was doing in the late ’30s and ’40s, which is pretty wild,” Last Gun tells me in his studio. The Montana-born artist stayed in Santa Fe after graduating from the Institute of American Indian Arts in 2016. He shows at Hecho a Mano in Santa Fe, and just landed his first New York solo exhibition. The TPG also found early success in Manhattan, breaking through in a group show at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (now the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum).

The TPG was devoted to pure abstraction; their true medium was light, depicted with scientific precision and wielded as a mystical portal to transcendent states. Once Within a Time will feature the soft forms and sensuous gradients of Agnes Pelton (1881-1961), the group’s de facto guru.

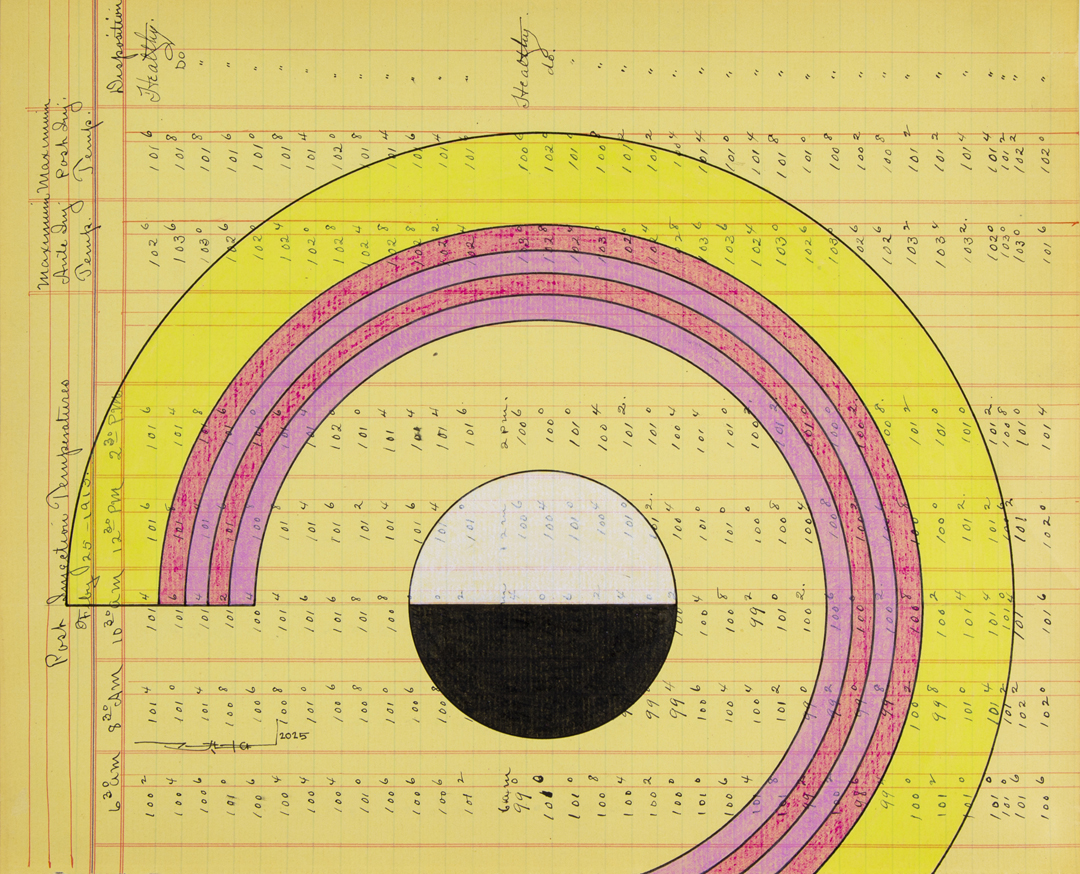

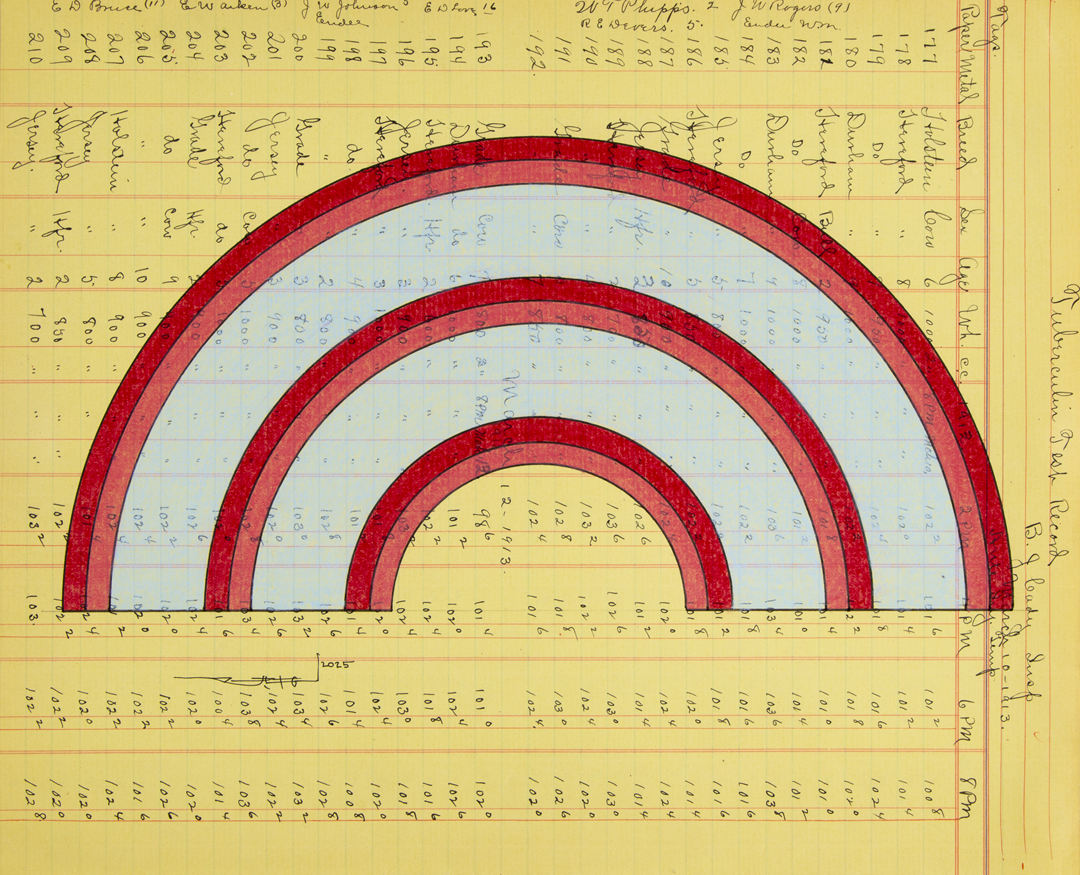

Last Gun’s abstraction is more hard-edged: for the International, he’s painting a crisp geometric form on historical ledger sheets from around the time of the TPG. The series will comprise eight pieces and appear near Pelton’s artwork at SITE.

The vintage paper is a reference to ledger art, a modern tradition among the Plains Indians (including Last Gun’s tribe) that grew out of hide painting. But the repeated form Last Gun has chosen—a skinny triangle that points to the heavens—is classic TPG. “It’s kind of a collision of histories, my own history and then [the TPG], and trying to figure out how those mesh,” Last Gun says. “They were trying to capture something that’s not easily captured—spiritualism, energy, the other side. My work [is in] a very similar vein in terms of capturing… the experience of seeing this vastness.”

Joanna Keane Lopez can feel explosions when she’s visiting her childhood home in Socorro. Her family’s land neighbors a munitions testing center operated by the U.S. military.

“One of my father’s earliest memories is of his grandfather’s adobe home cracking because of the bombs that were going off next door,” says Keane Lopez. As she developed her long-running practice of adobe construction, which fuses Pueblo and Spanish technologies, Keane Lopez started to unearth histories that are folded directly into New Mexico’s mud.

She extracted 1920s newspaper clippings from adobe bricks (“like ghosts encapsulated”) and sifted through glass shards striating years of alcoholism in her family. Inspired by her mother’s career as a journalist and filmmaker and her father’s anti-nuclear activism, she puzzled over how to surface the invisible poisons hiding in the region’s often-romanticized landscapes.

They literally assembled the nuclear bomb… in this space of intimacy.

Keane Lopez lives between New Mexico and California and regularly teaches adobe-building workshops. She also uses her architectural skills in her sculptural work: her section of Once Within a Time at SITE will feature an expanded version of her 2024 mixed-media installation Batter my heart, three person’d God.

The piece recreates part of an adobe home in White Sands that was seized by the U.S. military and later used by the Manhattan Project as the Trinity Bomb’s last pit stop. “They literally assembled the nuclear bomb in the bedroom, in this space of intimacy where you’re born, where you make love, where you die,” says Keane Lopez. “That’s where the Nuclear Age began.”

The invasiveness of this pivotal historical moment resonates with the tale of Lilli Hornig (1921-2017), a chemist who worked on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos. Alemani chose her as an official “figure” over more famous con-temporaries like Robert J. Oppenheimer. One of the few women scientists on site, Hornig was initially assigned to work on plutonium research but was quickly sidelined due to sexist restrictions related to radiation risks to reproductive health.

Daisy Quezada Ureña is fresh off an urban archaeological dig when I catch her between classes at the Institute of American Indian Arts. By day, she’s the chair of IAIA’s Studio Arts Department, and in every other waking moment the California-born, Mexican American artist has been digging around to unite shards of the city’s past.

That means a lot of time spent in museum archives, but also in the actual dirt: the day before, she met with an archaeologist at the downtown construction site for a new wing of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. They rooted through broken earth that will soon be sealed under fresh foundations.

In a front room of the Palace of the Governors on the Santa Fe Plaza, a historical seat of government that’s now part of the New Mexico History Museum, Quezada Ureña will stage an elaborate architectural intervention for Once Within a Time. She’s cagey about the exact details, but it involves bracing the room with shoring posts and filling it with charged objects and materials.

“I’m thinking about what was immediately accessible outside of those windows” during Spanish, Mexican, and U.S. colonial rule, Quezada Ureña explains. “What actions were taking place, what massacres occurred, what violence?” Earth from the O’Keeffe dig will appear in the room, along with firearms from different colonial eras, Indigenous artifacts from the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture—and possibly a bell that is said to have signaled the start of the Pueblo Revolt.

In gathering this conspicuous stuff, Quezada Ureña draws attention to the Plaza as a stormy public arena—once traversed by the explorer (and former African slave) Estebanico in the early days of colonial incursion, dominated by figures like the saloon-keeper Doña Tules during Mexican rule, and still symbolically contested in the mythic battles between Zozobra and the Fire Spirit. Alemani weaves all of these figures into the show’s larger curatorial framework.

“Retelling through the materials is really interesting to me,” Quezada Ureña says. But she’s also been asking herself, “How much are you able and willing to hold?”

Nora Naranjo Morse (Tewa) has been roaming the Rio Grande, from her Northern New Mexico home in Santa Clara Pueblo all the way to the border line.

She’s foraging for used burlap bags from chile roasters, envisioning a series of towering, semi-figurative sculptures for the Wheelwright Museum. The works will evoke “pathways of interaction” among and between the Pueblo people and transformative colonial forces

On her first visits to the Wheelwright’s formidable main gallery, which echoes the circular layout of a Diné/Navajo hogan, she thought, “The work that I do is shifting and experimental, and how do I fit into this place that has been so revered?”

She reasoned that her humble materials actually align quite well with the Native-art-focused museum’s section of the International. The artist traces the Indigenous roots of her recycling ethic: “During the Depression, most of the southern Pueblos could not afford turquoise and silver, so they initiated this whole genre of art by collecting plastic and all of these things that they started turning into jewelry.”

There are many stories in the one. And indeed there is one story in the many.

This spirit extends to Native storytelling. Naranjo Morse says, “We’re sort of making these cycles of becoming something all the time; becoming something new is really intriguing for me.”

Apart from Reggio’s film, an early point of inspiration for Once Within a Time was the Indigenous concept of “circular storytelling,” as expressed by deceased writer N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa, 1934-2024). In his poem “In the Telling,” he writes, “There are many stories in the one. And indeed there is one story in the many. We roll on wheels of words and dreams.”

For New Mexicans, Momaday may be the most poignant “figure of interest” in Alemani’s curatorial conceit—his passing still fresh, his voice alive in a culture he long shaped with story.

Alemani says that in her research process, she sought “endlessly repeatable” stories that could fill “a space where your ideas can be effervescent and… find a fast pace.” As with any symphony, the conductor may wave her baton, but it’s the orchestra that keeps the rhythm. The SITE Santa Fe International—with its many cadenzas, counterpoints, and recurring motifs—is now in the hands of the artists.

Update 06/24/2025: This article has been updated to reflect Cecilia Alemani’s evolving curatorial process. At press time, she had selected twenty “figures of interest” to highlight in the show, but by the show’s debut it had grown to twenty-seven.